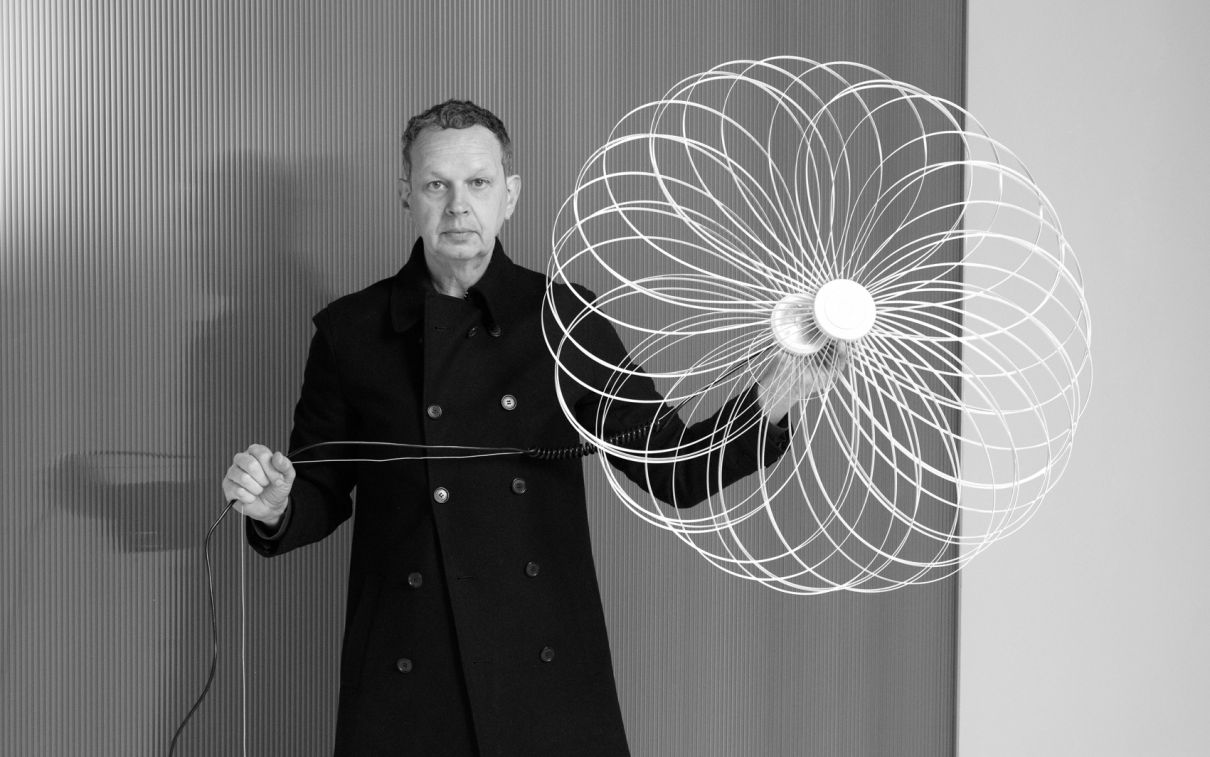

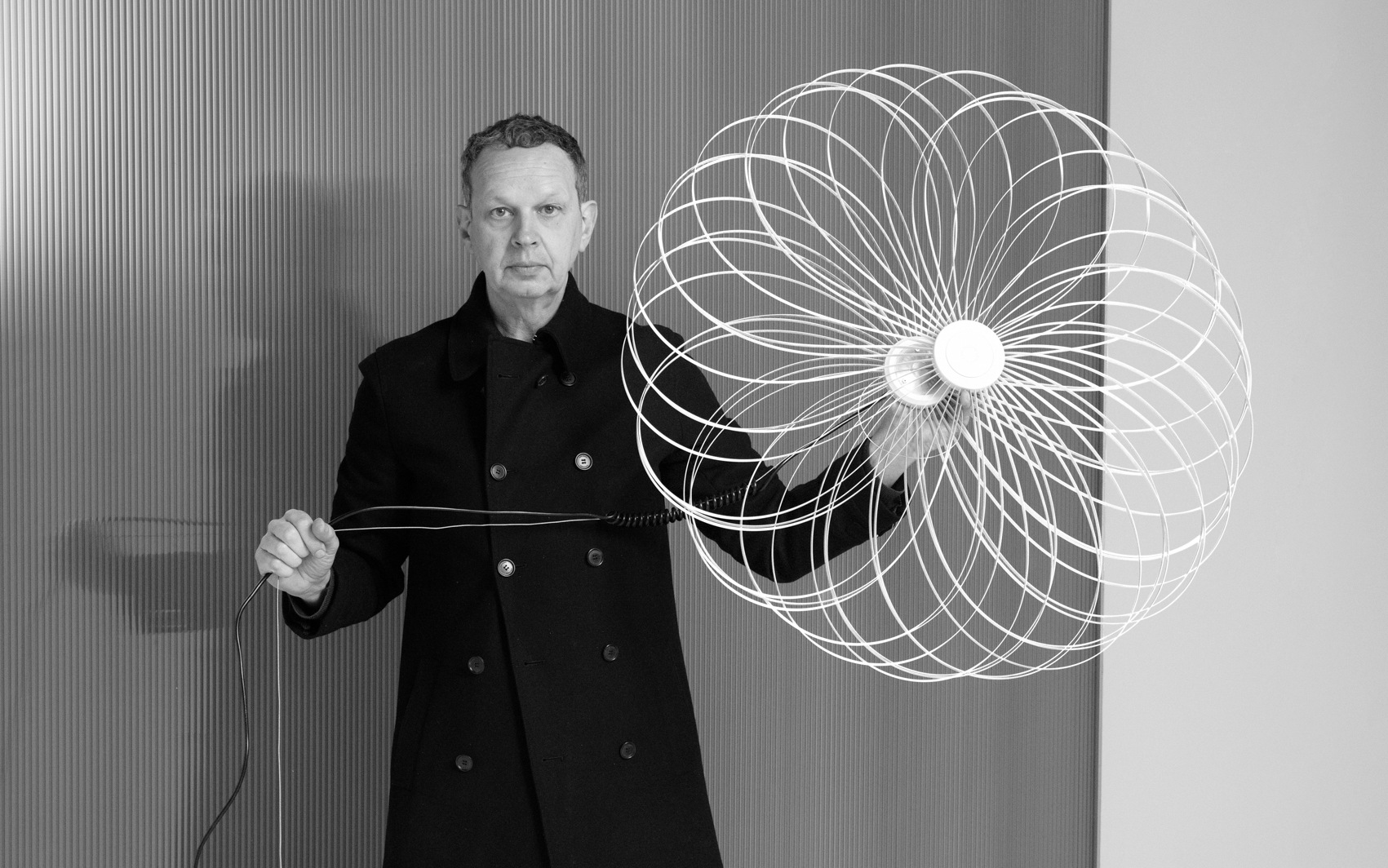

Five Questions For Tom Dixon

“You make things for fun and then people start buying them,” is the philosophy of British super-designer, Tom Dixon.

Tom Dixon has always made things that people have wanted to buy. The reluctant designer, 60, stumbled into the profession in the 1980s without a formal design education. After dropping out of art school, he went from playing bass guitar in the band Funkapolitan and running several nightclubs to creating welded objects from salvaged scaffolding, hubcaps and old grates (having taught himself to weld while recovering from a motorcycle accident, as he had wanted to repair his motorbike). He rose to prominence with a line of industrial-scrap-turned-furniture. “You make things for fun and then people start buying them,” he recalls. “I was astonished that people liked my ideas so much that they were prepared to pay for them. That was what made me a designer in the first place. Otherwise, I’d have been doing something else.” Soon he was designing the iconic S chair for Cappellini, leading the rejuvenation of Habitat as its creative director and being awarded an OBE by Her Majesty the Queen.

Today, one of Britain’s most successful designers, known for his furniture and lighting collections and interior design practice Design Research Studio, Dixon focuses not only on designing but also on challenging industry norms. He’s interested in big business, having combined the creative with the commercial throughout his career. Frustrated by how difficult it was to distribute furniture in a complex and old-fashioned system, he reflected on how he could make it more modern and held various ‘straight-from-the-manufacture-to-the-consumer’ events. Dixon says: “I don’t really see a distinction between the design part and the commerce part and, of course, in the modern world, you have to be super creative about how you sell because everybody else is being super creative about how they sell.”

Dixon is atypical compared to other designers since he has more contact with these two ends of the business than others who work somewhere in the middle. He finds satisfaction working on the initiation of a concept all the way through to its interaction with the user. He says: “Most people have a design studio, they might work for a factory or a retail firm, but they don’t really get stuck in to either world. In my career, I’ve had intimate experience in making things with my own hands, getting dirty doing it, and the more glamorous front end of selling stuff, retail, or communicating it, building a reason to buy stuff. You’ve got to be more convincing in so many ways, but also what gives us our edge is being quite close to how things are made. That has always been my inspiration from the beginning; it’s the tools of the trade and the materials that you make things from.”

Going to work these days still feels like play for Dixon, not having lost any of his early enjoyment, as he set up his business in such a way that he could dabble in a variety of trades; some days working more like an engineer or a graphic designer; other days like a businessman or a branding guy. He embraces change and is easily distracted. As soon as Dixon gets bored with one project, he switches to a new field. Anything that he hasn’t done, he would be interested to try. We sat down with Dixon to discuss creativity, innovation and staying fresh.

After 18 years since the creation of your eponymous brand, do you still have the same enthusiasm for the job?

If I lose enthusiasm for doing the same thing, I do something new. This is the wonderful thing about design: it’s not really a job. It’s a job that you apply to everything else, so if I decide that I’m going to be an architect or a designer of hospitals, then, in principle, I can do that, or I can get into electronics. As soon as I get slightly bored, I’ll be making a chair out of mushrooms and then I’ll be excited again, so I don’t ever get tired of it, and all it does is to throw up more possibilities. The more you know, the more there is to know.

How has The Factory — your pre-production small-batch manufacturing workshop where ideas can be tested out, prototypes created and customers directly engaged — changed the way in which you work?

The Factory is trying to get back to a point where I’m dragging my designers and even some customers off their computers and getting them into a space where we make stuff, which is what we do. The objective was also to have a place where I could experiment in London again. The reality is that we live in a wonderful and interesting world and real things exist. My designers don’t get a sense of proportion, colour, smell or weight of an object on a computer, so The Factory is for me to confront my team with what it is to make stuff and be a bit looser, and then to try to get the customer involved in either making stuff or seeing it being prototyped. That’s what interests me, so I want to show it to everybody else. So, The Factory tomorrow will be a photo studio and then probably a perfume factory within a month, and it keeps on evolving.

You have said that you live in a permanent state of dissatisfaction with your body of work. Is this what pushes you to keep going and try new things?

Yes, I can’t ever look at anything without thinking I could have done slightly better. But it’s not because the thing is bad; it’s because I know more. Because I didn’t have formal training and didn’t get a certificate to say I was allowed to do this, every day is still magical because it was never a decision of mine to be a designer in the first place. It grew on me as I made things.

Do consumers want constant creativity anyway?

No, I don’t think they do at all, but the press does. Consumers find it very hard, particularly in interior design, to move at that pace but, of course, the whole industry, retail and communication, is dominated by the need for new. In principle, it’s very hard to do that, but what I love about it is exactly that because I’m as bored as the press is, so producing new ideas every week is great for me. I’m always grateful that we’re not in the fashion business because although there’s pressure for newness, it’s not that cycle. It just can’t be every month, three times a season. It has to be a bit slower.

What legacy would you like to leave behind?

I don’t know. I never really think about legacies. If I’ve managed to do something useful, that would be good. I’m still trying to work out what that is. But I think the pressing questions about ecology, sustainability and changing the world are the ones that everybody should try and make an impact on.

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Summer issue themed on Exploration. To subscribe contact