Liverpool Biennial: Stomach that!

Liverpool Biennial, the largest festival of contemporary visual art in the UK, runs until 27 June 2021.

How do we assimilate, digest what is going on in the world? How can we look at our ports, symbol of globalization, and not fear what is coming from outside, or abroad, in times where refuges and migrants are seen as a problem rather an opportunity?

Curated by energetic Manuela Moscoso, this year’s Liverpool Biennial addresses these very questions around the theme The Stomach and the Port: showcased throughout the city is the work of 50 leading and emerging artists and collectives from 30 countries around the world. A city at the heart of contemporary issues – both on a collective and an individual level – Liverpool is a melting pot, a fluid body, a mouth that accepts, speaks up, or rejects.

“At the heart of this Biennial is Liverpool’s history as a port city, an active agent in the process of modernization, change, and colonialism. Through the visible and invisible dynamics of the port’s past, this Biennial envisions different forms of being human and explores what bodies have the potential to be”, the Biennial team explains.

Teresa Solar’s outdoor installation Osteoclast (I do not know how I came to be on board this ship, this navel of my ark) (2021) uses body parts to express a wider message: Osteoclast is composed of five oversized, bright danger-red kayaks, each in the shape of a human bone. The sculptures are anchored on the maritime history of Liverpool, drawing parallels between bones – which allow us to move, are carriers of tissues, veins and cell communities, pathways for messages between brain and the body, shelter for our organs – and vessels, vehicles of migration, transmitters and connectors of bodies and knowledge. In contrast to the enormous ships that were, and still are, built and docked in Merseyside, Solar’s kayaks, turned into a disarticulated skeleton, set the human body at sea level and evoke the fragility of the human body over the sea. “At the same time, they also celebrate our capacity for transition and transformation”, Solar comments.

“The Stomach and the Port reflects on systems of exchange, how borders are not only geographic but also political and subjective constructs. Rooted in decolonizing our experience of the world, the artists collaboratively present a re-calibration of the senses and a catalyst for change”, adds Moscoso.

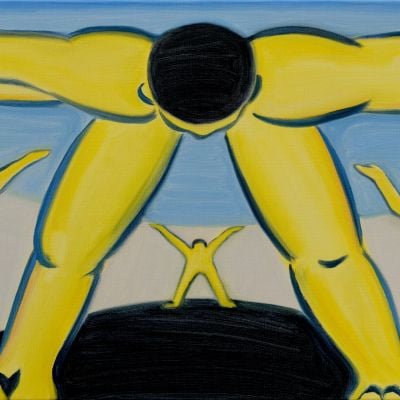

Illustrating this reflection are Larry Achiampong's Pan African flags scattered around Liverpool’s city centre. The colours of the flags reflect Pan African symbolism: green, black and red represent Africa’s land, people and the struggles the continent has endured respectively, while yellow-gold represents a new dawn and prosperity. With some designs featuring 54 stars that represent the 54 countries of Africa, the flags evoke solidarity and collective empathy – while some of their locations speak to Liverpool’s connection with the enslavement of West Africans as part of the transatlantic slave trade. Iconic and highly visible, the flags are a clear reference to community, motion and the human figure in ascension.

“Exploring concepts of the body, the Biennial draws on non-Western thinking that challenges our understanding of the individual as a defined, self-sufficient, entity. Instead, the body is seen as fluid, being continuously shaped by, and actively shaping its environment”, adds Moscoso. Set near Tate Liverpool on Canning Dock Rashid Johnson’s Stacked Heads (2020) evoke a sense of collective anxiety: the outdoor sculpture, a totem of two black cast heads made from bronze, is furnished with yucca and cacti plants that give the heads a mad silhouette and personality. While the plants were selected for their endurance to harsh winds and saline water of the Mersey, their resilience – as well as the location of the sculpture - speak to the origins of present-day racial discrimination and violence – the transatlantic slave trade – of which Canning Dock was an early facilitator.

French artist Camille Henrot's works explore obscured aspects of motherhood in relationship to the feminine body; a huge photomontage by Linder - Bower of Bliss (2021) – inspired by the act of transformation and the daily life of women in Liverpool throughout history; or Erick Beltrán's musical journey Superposition (2021) played across a fleet of Liverpool’s ComCab taxis, the Biennial has taken over the city, exploring the rich theme in countless directions.

“This Biennial’s creative vision has produced a vital and thought-provoking edition with The Stomach and the Port, addressing some of the big questions of our times and overcoming significant challenges which the pandemic has presented along the way”, concludes Biennale Director Dr. Samantha Lackey.

In these challenging times, when traveling isn’t always possible, the Biennial’s Online Portal is another great way to discover the many works and installations: a platform presenting an introduction to each of the artists and entry points, along with a dynamic digital programme Processes of Fermentation, it combines live performances, artist interviews, curatorial videos, artist-led discussions and workshops, a film programme and podcasts.

If you are able to travel to Liverpool, Hope Street Hotel sits in the city’s Georgian neighbourhood, across the Liverpool Philharmonic, steps away from the monumental cathedral. Housed in a Venetian-style building with an attractive facade that was built in 1860 to resemble a palazzo, the hotel now welcomes minimalist interiors, a collection of modernist furniture, exposed brick walls and natural light: perfectly calm after a day exploring art venues. Partnering with the Biennial, it welcomes most artists and collectors.