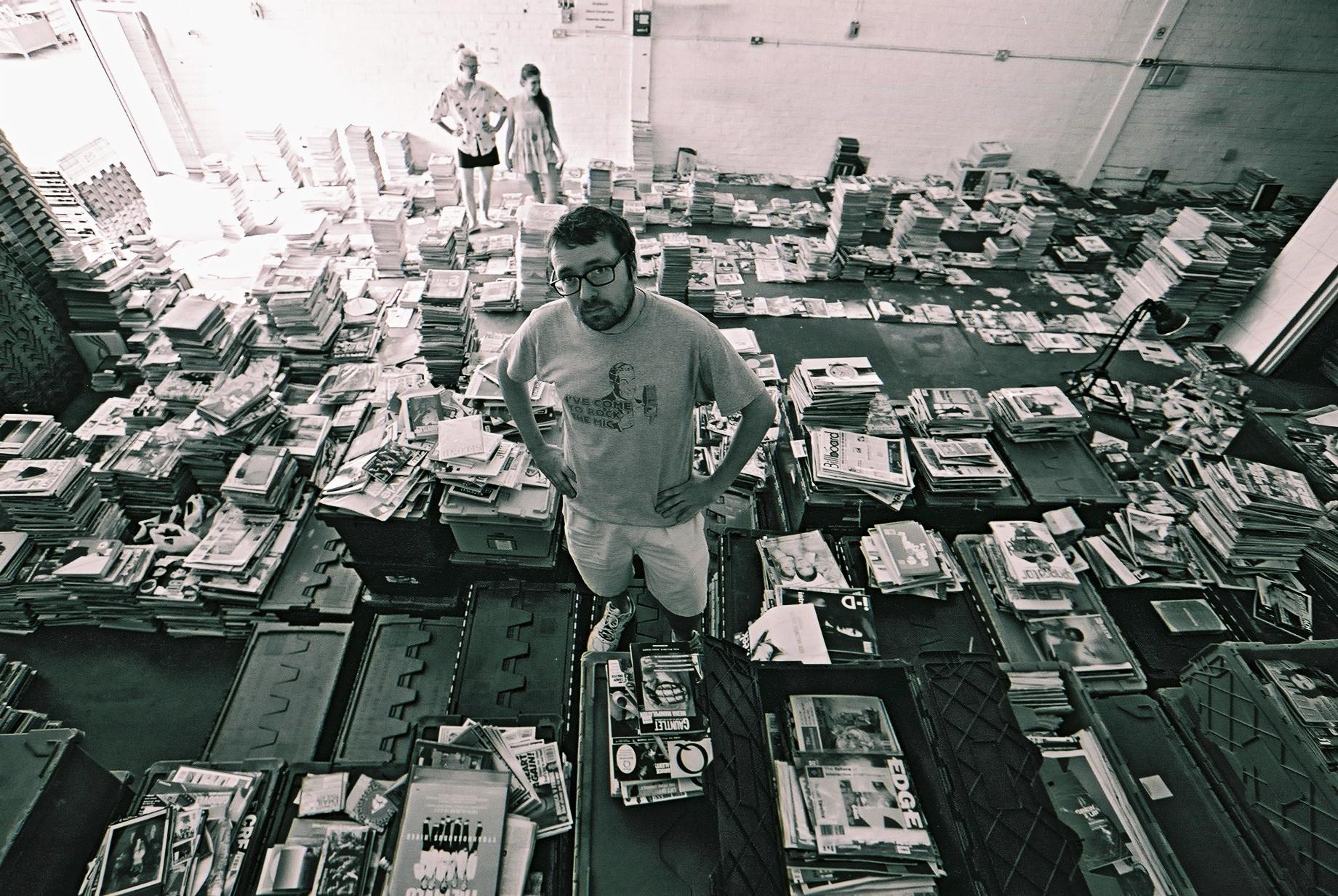

Back To Black And White

The Hyman Archive — the world’s largest collection of magazines — is a defiant celebration of popular culture in print.

Like many kids growing up in the 1970s, James Hyman hoarded comics and cartoon books. But as an adult his obsession grew deeper, and he stockpiled a vast collection of popular culture print magazines — ranging from Radio Times and Playboy, to NME, Which? and Billboard, and many more.

“Back then, magazines were your Internet,” he recalls. “Your information sources were dependent on magazines if you wanted to know or talk about what was happening.”

Hyman found magazines indispensable for his first job in the 1980s: writing scripts for presenters on MTV. “The VJs (Video Jockeys) had to fill airtime, to talk between the videos they were showing. Prince, Madonna and Bowie, they would be played on rotation a lot, so you needed to talk about them. Where did that information come from? Magazines.”

Fast forward 30 years and Hyman has amassed a treasure trove of more than 5,000 different titles that comprises of over 120,000 individual magazine issues, spanning from 1850 to the present day. Predominantly in the English language, subjects include film, TV, pop video, art, fashion, architecture, interior design, trends, youth, lifestyle, women, men, technology, sports, photography, counter-culture, graphics, animation, and comics. You can’t find many of these magazines anywhere else in physical or digital form.

It’s a collection that has earned him a spot in the Guinness Book of World Records, but he isn’t stopping there. His archive continues to expand at approximately 30 percent annually thanks to public and private donations. His goal? To digitise every last page, securing their place in history forever.

“I’m obsessed with pop culture,” he says. “It’s very sad that physically a lot of this stuff just disappears. I'm a real advocate of preservation, but how are you going to do that unless you digitise it?”

Subscribers to The Hyman Archive will be able to research and reference using an in-depth tagging system combined with OCR (optical character recognition), says Hyman. “You can run sophisticated searches, such as connections between Bob Dylan and Tarantino in Vogue magazine; or how Kate Moss relates to the Burberry brand; or specific pictures of Jack Nicholson smoking in the 1980s. We’re going deep into A.I. and metadata to provide incredible analysis beyond simple search results. Think of it like a YouTube or Spotify of magazines aimed at the Creative and Academic industries.”

This mass-digitisation project is predicated by the changing legal environment for copyright that makes a project such as this possible, says Hyman. The archive strives to respect copyright and is dedicated to the protection of rights, ensuring photographers and contributors are paid for their works. If he obtains the industry-approved license, with the right resources, the entire archive could be digitised and available to a global audience on a subscription basis.

But, at the moment, the archive is only available if you visit it in person, in south east London at an enormous media-archiving facility called The Stockroom. “We consider it the final resting place for magazines,” he says with a smile.

Hyman’s clients so far have not simply been the nostalgic old-timers but the digital-fluent Twitterati. “Millennials absolutely love magazines, a bit like the vinyl revival you’re seeing now. You find that a lot of millennials have a malaise of digital; they want to touch something real, their eyes are burning from screens,” he says. People from the academic and creative industries pay a daily rate to access the entire physical archive. With his colleagues Tory Turk and Alexia Marmara, Hyman will also provide a consultancy service for a fee.

In the future, Hyman has ambitions to create a magazine museum, a cultural hub where people could come to join a community for study, exhibitions, talks, research, all to complement the archive and its content. Many see the value in his service.

“The problem with digital culture is that the people who are digitising are deciding what is important and what is not important. And a lot of stuff that is considered quite ephemeral has vanished,” says Kirk Lake, author, screenwriter and former manager of one of James's regular haunt, Notting Hill's Book & Comic Exchange. “People think the stuff from the 1970s is important so they collected it, but if you look at the 1980s and 1990s, that’s a lost period.”

Indeed, the era of print media has made a surprise comeback. When the Internet was born, the future of print was in doubt. But in the years since, magazine titles such as The Economist, Vogue, Wallpaper* and Private Eye have defied the advertiser exodus and changed consumer reading habits to have their best years ever. Vogue’s June 2016 issue was its largest ever, and 55 percent of its pages were advertising, a record. Likewise, Wallpaper* published a record 508-page edition last September with nearly half of the pages paid-for. The Economist Group boosted operating profit from £59.3 million to £60.6 million in the year to the end of March 2016, even though print advertising fell 18 percent the previous year. Private Eye recently enjoyed some of its highest circulation in three decades, as of 2015 up 10 percent since 2011.

The longevity of print may be down to the perception of printed matter as high quality while digital quality is mixed. But from the perspective of The Hyman Archive, the two go hand in hand. “It’s a conundrum, you have to be on the Internet to connect to this incredible print archive,” says Hyman. “What people have to understand is there is a wonderful synergy between print and digital. And that will stay.”

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Celebration Issue, December 2017. To subscribe contact