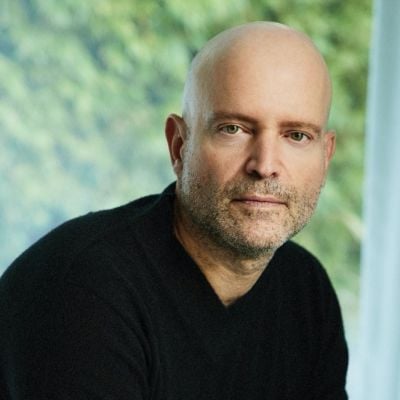

Tough Love

Despite a legendary career on the court, Martina Navratilova’s path to public affection was not always a smooth one.

Few tennis champions — if any — can touch the legendary Martina Navratilova. The list of her achievements is as long as your arm: Grand Slam singles champion 18 times; Grand Slam women’s doubles champion 31 times; Grand Slam mixed double’s champion 10 times; and holding the world number-one ranking for seven years. Her record as the number one in women’s singles (1982–86) remains the most dominant in professional tennis to date.

For four extraordinary decades she was at the top of her game, a champion in her field, as well as a philanthropist and social activist; a rare combination of absolute ambition and pure grace.

Her story is a testament to unbending perseverance and self-belief. Growing up in her home country of Czechoslovakia during the communist era made it almost impossible to pursue her dream. Already a star at the age of 18, she was told by the Czechoslovak Sports Federation that she was becoming too Americanised, and she should go back to school and make tennis secondary. She applied for asylum in the US and was granted temporary residency and, as a result, was stripped of her Czech citizenship.

Four years later, Navratilova won her first major singles title at Wimbledon 1978. It was a bittersweet moment, she recalls at an event held in Singapore by luxury watch brand Avantist, for whom Navratilova is an ambassador.

“It was my dream to win Wimbledon but my father put that dream into my hand. He spent thousands and thousands of hours on the court with me. In all my life, there were probably only five strokes that my father didn’t say something [critical] about; maybe five that were perfect in his head.

“So here I was at a Wimbledon final and my father and mother weren’t there; they couldn’t come because of the travel limitations. I didn’t even know if they were able to watch the match because they certainly didn’t show it on television in Czechoslovakia. So, when I won, this dream that I’d had since I was eight years old, I didn’t have my family to share it with.

“But when I got to the locker room an hour later, my father called me. To this day I don’t know how he got the number, because it wasn’t easy back then. To make an international call from a communist country was an impossible mission. But he got me on the phone and that’s when I found out they had driven to Pilsen, a town close to the German border, and they watched the match on German television. After that I really started celebrating.”

Navratilova, a gay rights activist, came out as a lesbian in the 1980s. Although she says she felt comfortable with who she was, it changed her reception on the court for much of her career.

“I came out in 1981 after I got my US citizenship. I wanted to come out earlier but I really couldn’t because it was a disqualifier… They could have said ‘no we don’t want you here’. I was always comfortable with my sexuality; it didn’t make a difference to me. But I knew my life would be more complicated because it was so unacceptable back then. I had nothing to hide and when it happened it happened.

“It was the summer of 1981. I had just come out, got my citizenship and I lost to Tracy Austin in the US Open women’s singles finals. When I got the runner-up trophy, people started clapping. I finally broke down and started crying, because I felt accepted by the crowd, and I was grounded, and I knew I was home. Even though I came from a communist country, even though I was gay, and even though I lost, they loved me. It was really special.”

But after that, crowds weren’t always as welcoming. After she started winning and playing her trademark aggressive attacking game, “a lot of people weren’t clapping”.

“I always had a yearning to be accepted and loved, and I didn’t get it for many, many years. To this day I must say I am jealous of Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer, who are always the home team when they are playing. For much of my career I didn’t have that. Even playing in the finals of the US Open in 1985, the home crowd was going nuts for Hana Mandlíková to win that match. It killed me.

“It was difficult times. I’m pretty sure that if I had been straight, the reception would have been quite different back then. But at the end of my career everyone loved me and now I am a hero. That’s just how it goes.”

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Celebration Issue, December 2017. To subscribe contact