Antarctica By Ice-Breaker

Antarctica is one of the last unspoilt destinations on Earth. How can we ensure it stays that way?

After an enormous iceberg – the size of Delaware – broke away from Antarctica's ice-shelf this year, the world's Southernmost continent has become the new posterchild for climate change. It will almost certainly result in more visitors to the region.

Industry body IAATO (International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators) was founded back in 1991 specifically to promote the practice of responsible private-sector travel to the Antarctic. It noted 15 percent more visitors to the region this season compared to the last, and numbers are expected to carry on growing.

The appeal lies in reaching the seemingly unreachable. If anywhere delivers on that promise, it’s Antarctica: the iciest, coldest, driest, windiest desert there ever was.

I was introduced to the continent on the Hanse Explorer, a 48m ice-classed superyacht. Days were spent zipping around the Antarctic Peninsula alongside humpback whales on inflatable RIBS, kayaking with seals and penguins for company, or posing for photos on ice floes. We may have been following in Shackleton’s footsteps, but I doubt he had the promise of rum-spiked hot chocolate, a four-course supper and a warm bed to return to. When expedition travel can be enjoyed in such supreme comfort, it’s little wonder visitor numbers are soaring.

The biggest luxury of my trip, however, wasn’t the onboard sauna, five-star service or even afternoon tea, served every day in the lounge. It was, instead, the completely unblemished natural beauty of the destination and the novel sense of total isolation it offered. We passed just one other boat in the seven days we spent sailing around the peninsula and were consistently outnumbered by penguins or dwarfed by towering icebergs. Our excited chatter was often drowned out by the earth-shattering noise of ice calving, as enormous sections of gleaming white ice broke away from the glaciers around us, smashing dramatically into the water below.

The fear now, of course, is that this continent’s pristine white palette will be stained with a dirty great human footprint. Or thousands of them. Beyond the growing number of superyachts sailing into the continent, there are mammoth tour operators bringing much bigger crowds into the region. As well as the wider issue of climate change, which is causing rapid growth of ice-free areas in Antarctica, these increased visitor numbers present a new type of threat. Is the region prepared for its new popularity?

“IAATO’s vision is that tourism will not change the environment or affect wildlife in any way,” says Amanda Lynnes, IAATO’s communications and environmental officer. “We have comprehensive procedures and guidelines to protect the sites and wildlife, including minimum distances and etiquette.” On the Hanse Explorer, I saw these procedures honoured in practice every day. Eyos

Expeditions (a full IAATO member), which accompanied us on the trip, made it very clear from the get-go that we would be respecting wildlife, not chasing after it. That’s not as prohibitive as it might sound. Humpback whales frequently approached our boats, and penguins waddled across our path, seemingly oblivious, on a daily basis. IAATO also imposes a limit of 100 passengers ashore at any one time, although with just a handful of guests on board, we were never in danger of breaking that rule.

Ben Lyons, CEO of Eyos, is infectiously positive about the region’s new popularity. “Travel and tourism to Antarctica inherently has benefits in that it creates exposure to a destination that is otherwise not seen and appreciated. By bringing tourists to Antarctica, you’re creating a whole army of ambassadors that have seen how special the destination is and understand why it is worth preserving.”

Many of the ambassadors Lyons speaks of, particularly those arriving on private exploration yachts, are highly influential, often with the ability to shape public discussion and policy. On our landing in Vernadsky, a Ukranian base where a handful of researchers are posted for lonely months at a time, the walls were lined with visitor photos. I spotted Bill Gates, members of the UK royal family and beaming superyacht owners among them. Far from being a hindrance, these visitors are often capable of pushing the boundaries of exploration.

“This last season, one of the yachts we were working with conducted the first manned submersibles dive to 1,000m in Antarctica,” says Lyons, by way of example. “This is true discovery, taking humans to places they have never been before, and opening up a potentially new world to study, understand and appreciate.”

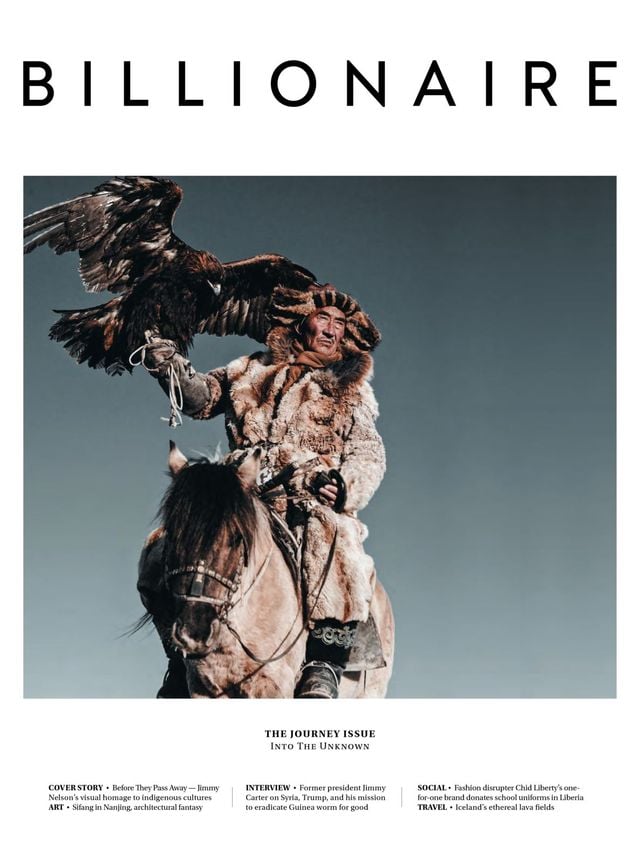

This article originally appeared in the Journey issue, September 2017. To subscribe contact