The Real Marfa

Marfa, a tucked-away town in Texas, is luring visitors on the strength of its artistic appeal.

The controversial Prada installation (c) Britt Collins

Tucked away in a starkly beautiful landscape in far-west Texas, the sleepy little town of Marfa has blossomed into an international art oasis. Ever since New York artist Donald Judd arrived in 1972 and planted his minimalist sculptures in the desert, it has become an unexpected draw for artists, dreamers and culture seekers.

Marfa is having another moment, propelled by the buzz of Californian artist Robert Irwin’s new 10,000-square-foot installation at Judd’s Chinati Foundation, 17 years in the making and now its star attraction. The desert settlement of less than 2,000 recently got its first high-end lodging, Hotel Saint George, and fine-dining eatery LaVenture, along with a handful of new art ventures.

Beneath a big blue western sky, my friend Jenny and I drove across hundreds of miles of desert on a two-lane highway. The wide prairie grasslands, where longhorns, coyotes, bobcats and antelope roamed, stretched on forever. When we reached Marfa, it seemed surprisingly small and deserted. The three blocks of the main drag — lined with Art Deco buildings from its glory days and mom-and-pop storefronts that kept weird hours — were mostly shut and straight out of The Last Picture Show.

As we stood in front of a derelict picture palace, watching a freight train rumbling through, an old-timer in a red baseball cap, poking his head out his car window, asked if we were lost. “Been living here for 70 years and still don’t know where I’m going,” he laughs, introducing himself as Brit Webb, Marfa’s newly re-elected 88-year-old councilman, who came here in 1944 and “started out by selling Studebakers from a garage that’s now a fancy art gallery”. He gave us a lift to Camp Bosworth’s studio, the Wrong Store, a small stone church, half-hidden by cacti, with a giant orange horseshoe out front.

Native Texans Camp Bosworth and his wife Buck Johnson, who met in Dallas after college in 1992, came to Marfa in 2001. Enchanted by its spare beauty, free-and-easy vibe, they never left. “I thought it was the end of my art career, but I flourished having the mental space and quiet,” he says, showing us around his light-filled cathedral-ceilinged atelier, with his three dogs trailing behind. “It’s like one big neighbourhood in the middle of nowhere; it’s vibrant, got a few cool places, some art. We’ve got a great store, our house and studio, and everything’s paid off. I can breathe out here.”

It’s extraordinary that so much inspiration can come from such a remote locale. Elise Pepple, who runs Marfa Public Radio, was drawn to Marfa’s community spirit. “I love small towns because they’re to human scale and you can build relationships,” says Pepple, who moved a year ago from Maine, where she ran another rural radio station, and had previously lived in New York, San Francisco, Paris and Montreal. “For me it’s about people and stories. In big cities, people are switched off. There’s something unique about places where people still turn on the dial. And going home at night and seeing the stars is a magnificent luxury. And to anyone visiting, I’d say be curious, talk to strangers.”

After running into Webb again, we join him at the Lost Horse Saloon, the local honky-tonk that’s filled with vintage curiosities and characters. Ty Mitchell, who owns it and describes himself as “a rambler born under a wandering star”, looks every inch the outlaw with his eye patch and handlebar moustache. Webb entertains everyone at the bar with stories of his wild youth and dance-hall days at Hotel Paisano and shows pictures of his college sweetheart. When ‘Sweet Home Alabama’ comes on the jukebox, he springs up on his rickety cane and has a whirl with Jolene, a musician who works as a chef at Planet Marfa.

I get chatting to a rangy silver-haired rancher in a Stetson, born and bred in Marfa, with generations of his family buried in the cemetery. “It was as quiet as a church and now we’re overrun,” he says. “Most of us here don’t care about art. We’re trying to survive. That Prada store is the dumbest thing I’d ever seen. Three weeks after it opened someone broke in and stole all the shoes.” Still, he enjoys talking to all the “fascinating folks coming through”.

A cow girl bartender (c) Britt Collins

While art tourism has rescued the old cow town from decline, the surge of visitors and rising rents has inevitably created tensions as long-time residents get pushed out to the fringes. But the maelstrom of different societies coming together — old established ranchers, cowboys, artists — gives Marfa its vitality and an alluring culture and climate. Then there’s the land — the endless sweep of unspoiled desert and mountains — that make it so magnetic and drew all the big-city artists and iconoclasts to the tiny outpost in the first place. As the local saying goes: “Marfa, tough to get to, tougher to explain, but once you get here you get it.”

On another evening we found ourselves on the edge of town, looking out into the vast emptiness for Marfa’s mystery lights. The luminous streaks first seen by a cowboy in 1883 while herding his cattle across the plains have haunted that stretch of highway since. The lights never appeared, but I couldn’t stop marvelling at the spill of stars across the velvety-black West Texas night.

Essential Marfa

Stay

The Hotel Saint George, an 1880s-era hotel for cowboys and railroad travellers that had lain derelict for decades, has been reconceived as a dazzling-white 55-room modernist affair, with a ritzy restaurant and lobby bar showcasing paintings by local art stars, and a new home for the Marfa Book Company, a decades-long institution, in the lobby. The Hotel Paisano, set in a 1930s Spanish-revival building, is steeped with history, where James Dean and Elizabeth Taylor stayed while shooting Giant in the mid-1950s and still a hotspot for visiting celebrities. The courtyard, tiled, opulent and charming, is a lovely place to unwind for dinner and drink fresh-lime margaritas around the sparkling fountain. For those wanting to sleep closer to nature, El Cosmico offers a collection of vintage trailers, tepees and Mongolian yurts. Possibly the chicest campground, it features shaded hammock groves, a reading room, wood-fired hot tubs, and is the centre of Marfa-hipness with non-stop music festivals and cookouts. Recently the Brite Building, an arty two-bedroom loft, has become part of El Cosmico’s offerings.

Eat and drink

LaVenture inside Hotel Saint George, is a sleek white-brick space that’s the perfect balance of sparse-chic, where Austin chef Allison Jenkins whips up seasonal Med-inflected American small plates of handmade wild-mushroom ravioli, citrusy salads and fanciful artisan cocktails, has quickly become the best restaurant in town. Pizza Foundation, a weekend-only Marfa staple, serves amazing thin-crust pizza with the freshest, homegrown ingredients. The Capri, a jewel-toned canteen and lounge designed by a Hollywood set designer, sits in a dreamy wildflower-and-cactus-studded garden. Owned by the same people behind the retro-cool Thunderbird Motel, it hosts pop-ups and showcases desert-inspired Meso-American fare: mesquite bread, tempura-fried yucca blossoms, watermelon radishes and prickly-pear sorbets. Although it has been around forever, Planet Marfa, an offbeat open-air bar decorated with twinkling string lights and kitschy treasures, is something of an all-hours social club. It serves beer, wine and authentic Tex-Mex food and has a warm, laidback atmosphere with its happy mix of ranchers, hipsters and out of towners.

See

There are multiple collections to see at Chinati Foundation, a modern art museum housed in a disused military fort, and tours can take an entire afternoon to explore. Donald Judd created the place in 1986 for his own permanent, large-scale works and his contemporaries. Robert Irwin’s stunning monument to light and space, and John Chamberlain’s crushed-car sculptures are the highlights. The Marfa Ballroom, a dynamic non-profit arts space in a converted ballroom, is a brilliant alternative for those who don’t have the time for the Chinati. It has film screenings, a concert series and year-round exhibitions that are free to the public. The new Rule Gallery, the Marfa outpost of the Denver gallery, is in a craftsman bungalow and provides lodging to visiting artists who run it in exchange for room and board. Catch a show at the Crowley Theater, which took over a grain store and turned it into a performance venue for everything from plays to live music and films.

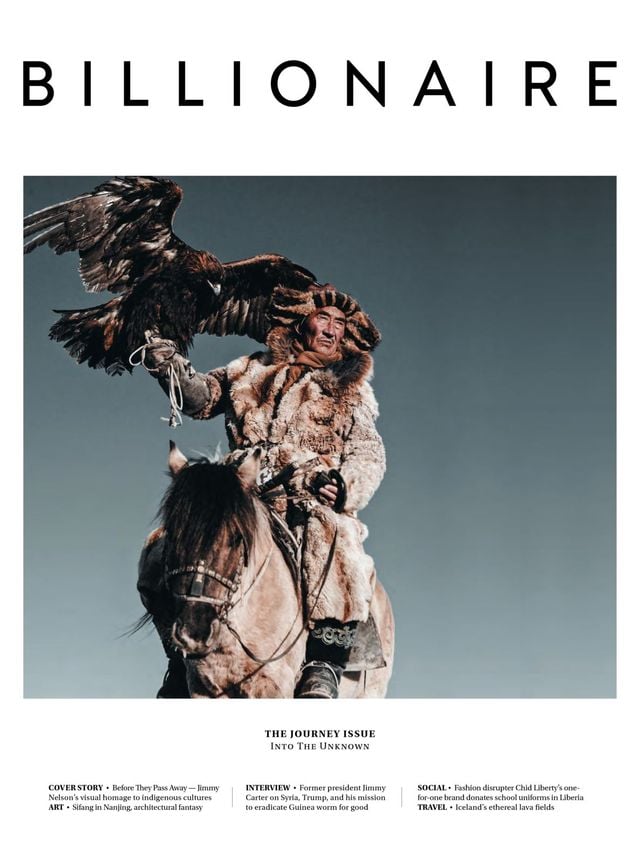

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Journey issue, September 2017. To subscribe contact