A Turning Tide

The scramble for modern and contemporary African art reflects an ideological and cultural shift.

On a dusty track about an hour south of Nairobi’s city centre, the smell of baking banana bread wafts from the doors of a corrugated iron house. “Welcome!” says Syowia Kyambi with an infectious smile, her arms wide. She bends down to sweep away the four dogs that have bounded to meet us, as we enter the studio and artist residency called Untethered Magic, run by herself, an interdisciplinary artist, and her co-founders, Kibe Wangunyu and Dennis Kiberu.

“When I was looking for land, this area was cheaper than the rest of Nairobi,” she explains. “I do work that is difficult for people to live with, about identity, power structures, history, racism. Stuff you don’t always want to look at. So, buying land was a big part of gaining independence so I didn’t have to compromise my work.”

Kyambi gives us a tour of her studio and her workshop, where she has created a bunny-like masked character called Kaspale, which she devised as a tool to speak about tough subjects. While she admits her work isn’t every collector’s cup of tea, Kyambi has been the recipient of several prestigious awards and grants including the UNESCO Award for the Promotion of the Arts; the Art in Global Health Grant from the Wellcome Trust Fund; a grant from Mexico’s External Ministry of Affairs; and commissions by the Kenya Institute of Administration. Her work is also included as a permanent installation at the National Museum of Kenya and various private collections.

Here in Nairobi, her focus is artist residencies; she points out the six structures which will soon be available for a residency program run by Untethered Magic. She shows the foundations of a vegetable garden and the plans for solar panels to get them off the grid. While she welcomes the growing buzz in Kenya’s art scene, she remains wary.

“The art scene is moving in a very commercial direction. There are no spaces for process or for people just to ‘be’, without having to make in a specific way. There is a set agenda for what is expected by collectors and institutions; I want this to be a safe space for artists to explore themselves.”

Recent times have seen an explosion of demand from collectors from all over the world for contemporary African art. In the last 10 years, the market share of African artists has increased 343.25 percent to 6.2 percent of the global total (valued at some US$65 billion) according to Articker, a tool exclusively partnered with Phillips Auction House. In the last two years alone, there has been a particularly sharp acceleration of nearly 50 percent growth in market share.

“There are a number of reasons behind this,” says Olivia Thornton, head of 20th century & contemporary art, Europe, Phillips. “The pandemic brought on a rapid, digital evolution across the art world and this in turn brought the continent’s plentiful talent to the fingertips of collectors around the globe. In addition, buyers are seeking to diversify their collections to show a fairer representation of artists active today. We are also seeing a continued trend for figurative art, a mode of representation mastered by a number of young African painters.”

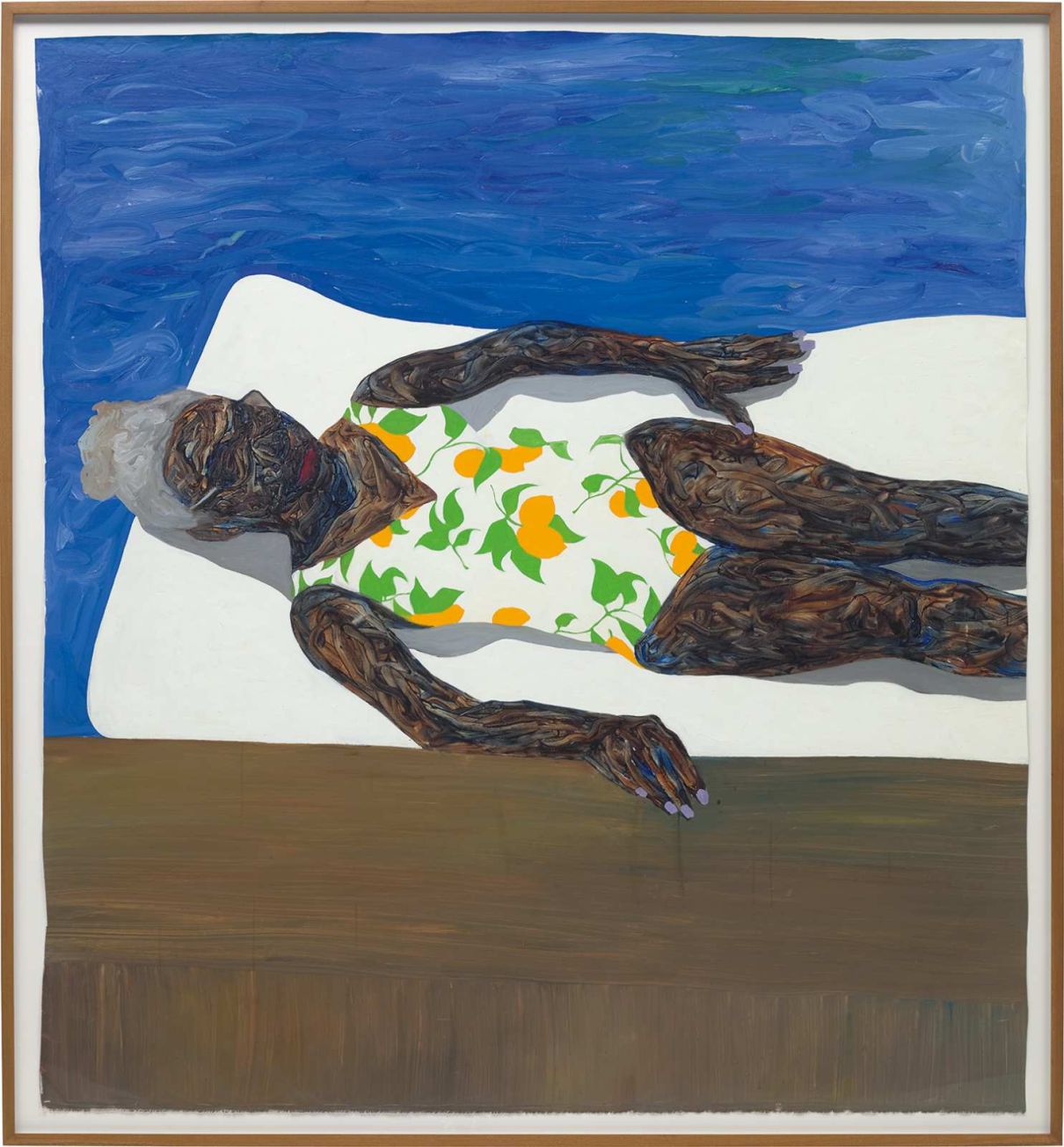

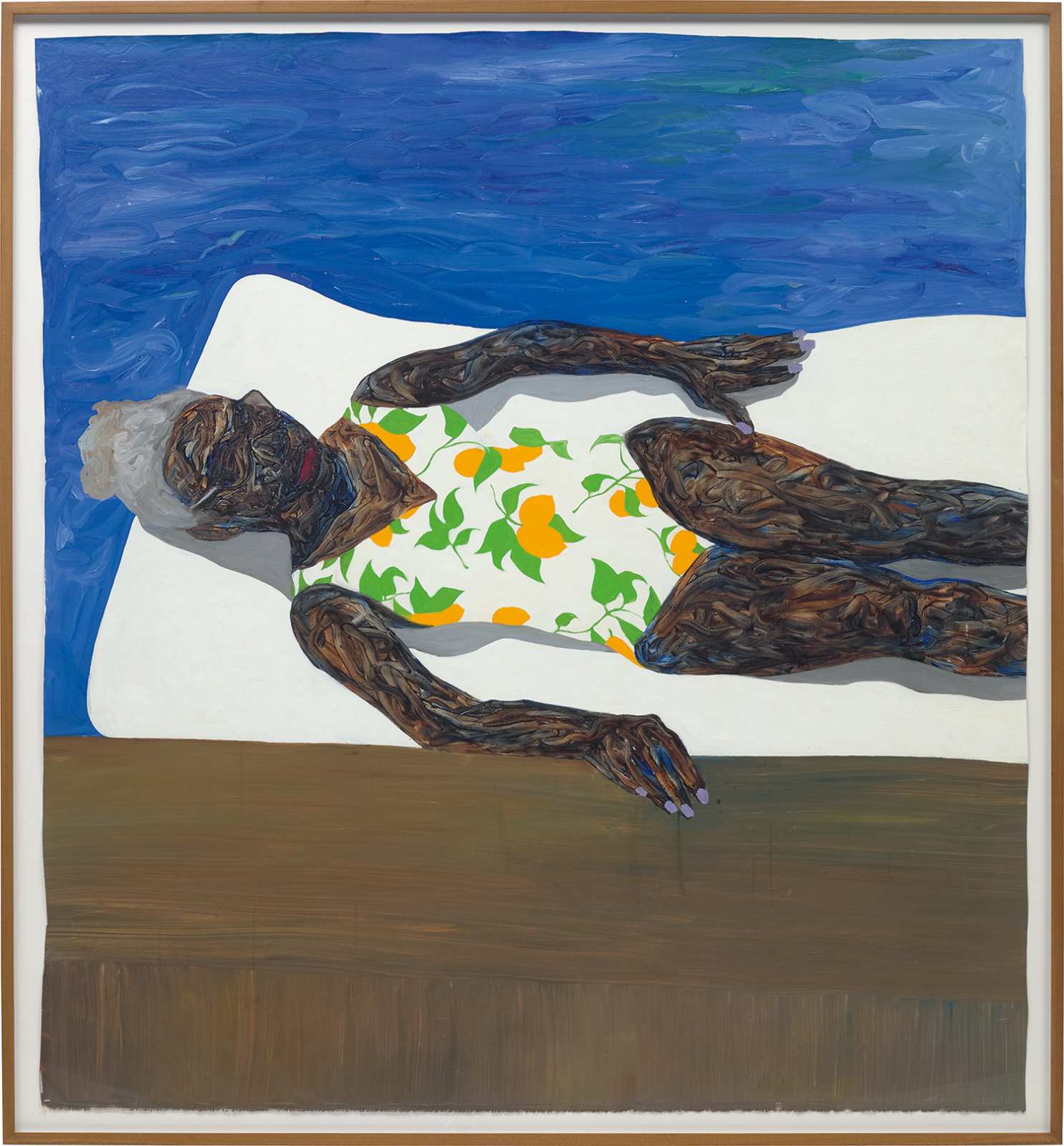

The ascent has been led by African artists Amoako Boafo, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Michael Armitage, Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe, Cinga Samson, Leilah Babirye and Ludovic Nkoth, according to Phillips, while world auction records have recently been set by artists including Oluwole Omofemi, Emmanuel Taku, Cassi Namoda, Godwin Champs Namuyimba and Serge Attukwei Clottey, some igniting bidding wars at auction before they have even so much as signed with a gallery.

Some say the journey truly began in 1989 with an exhibition put on in Paris’s Pompidou Centre called Magiciens de la Terre (magicians of Earth), which featured 100 living artists, half of them from the West, half from the rest of the world. Never before had contemporary artists from Africa and Asia been given equal weighting on such a major platform. It inspired the collection of African art by Johnny Pigozzi, heir to an Italian motor fortune, which remains today the largest collection of contemporary African art.

But even so, collecting in the genre didn’t properly kick off until around 15 years ago, when in 2007 Bonhams London began selling South African art at auction. The highlight was a 2008 auction when 250 lots made over £7 million in sales.

In 2012, the Tate Modern embarked on a mission to diversify its collections, earmarking a large chunk of its annual £4m-£5m acquisition budget to African art. It also dedicated a wing of its galleries to two contemporary African artists, Beninese conceptual artist Meschac Gaba and Sudanese painter Ibrahim El-Salahi.

Why wasn’t African modern and contemporary art collected before? “Lack of imagination; intellectual laziness; racism?” suggests Pascale Wheeler who was on the Tate Gallery African Art Acquisition Committee for 10 years. “But all of a sudden there was a real sense of momentum,” she says. She founded her gallery dedicated to contemporary African art, 50 Golborne, in 2014 and believes the swelling tide behind this segment will only continue to grow. “There is a growing number of African collectors — collectors tend to begin by collecting artists of their own country — and Black diaspora collectors who are keen to support artists from their country and culture of origin,” she says. These include A-listers such as Jay-Z and Beyoncé, Justin Bieber, basketball player Grant Hill and the Obamas. “I think that generalist collectors will acquire more African art as ‘Africa’, or notions related to blackness are so entwined with the contemporary global culture from music, fashion, celebrities, literature and dance.”

But, Wheeler caveats, “to grow much more, with regard to pure ‘African Art’, there is a need to have more and better art schools and residencies in some African countries that do not benefit from them.”

Ed Cross was one of the first galleries to offer solely contemporary African art, opening his eponymous space in 2009. He lived and worked in Kenya as an artist himself and became fascinated with the art scene. “The quality of the artists; they were cultural leaders and inspiring young people. None of them were being taken seriously by the West, which troubled me.”

He returned to London in 2009 and began selling art from African and the diaspora through the Ed Cross Gallery. Some of his top young artists from the diaspora include Anya Paintsil, Pabi Daniel and Abe Odedina; recently, business has been great. Over the last two years turnover has doubled every year. “There has been a sea change in perception,” he says, “people have woken up to the amazing work coming out of the continent. Also with the Black Lives Matter movement, institutions have been mandated to make sure their collections reflect diversity, which helps.”

Touria El Glaoui, the Franco-Moroccan entrepreneur behind the 1-54 Contemporary African Art fair, has seen the genre take off since she launched the fair in 2013. Now held annually in London, New York and Marrakech, with talks of an Asian outpost, 1-54 shows the work of some 50 galleries and 130 artists from Africa and its diaspora, with an approximate footfall of 10,000 per show.

Touria named the fair in reference to the 54 countries that compose the African continent, expressed as a ratio (“one continent, 54 countries”). “This is what we have fought for and now it has happened; artists from Africa having a stronger voice and visibility, African pride taking root all over the world,” she says.

The daughter of the artist, Hassan El Glaoui, Touria used to work for Cisco Systems, travelling Africa selling internet routers, falling in love with the continent. With her father being an artist, they would visit artist studios on the weekend or see local galleries; with the quality of the work, Touria wondered why these artists had no presence outside of Africa. “It bothered me because it was odd that these artists had no international voice. I felt a platform was needed, even though I doubted whether people would get engaged with it.”

But while great strides have been made, Touria believes there is a way to go. “There is still a gulf between the visibility artists are getting and the actual sales being made.”

Put another way, according to data company Art Market Research, there are currently only 12 African artists in its index of Top 1,000 artists. Before 2008 there were only three: Marlene Dumas, Irma Stern and Jacob Pierneef. (Value is judged on the average of 24 months’ worth of sales at 130 auction salerooms worldwide.)

Touria adds: “I would love for 1-54 to fade away because there is so much integration and visibility that it is redundant. That journey is very long and we’re not completely there yet. We still have a role.”