An Interview with Julio Le Parc

Julio Le Parc offers novel ways to view art, giving audiences a way to deal with uncertainty during times of political and social upheaval.

When Julio Le Parc arrived in Paris in 1958 on a French government scholarship, he had little more than the shirt on his back and a dream in his heart, as he settled into his tiny hotel room in Montparnasse. Just another unknown South American artist when he left Argentina, the Mendoza native chose Paris to forge a name for himself since it was the centre of the art world and his anonymity challenged him to demand more of himself. The French capital has proven to be a haven for Latin American artists escaping oppressive regimes. Although Le Parc may be known today as a pioneer of Op Art and Kinetic Art, he is not one to be limited by labels and refuses to be associated with one certain style or theme in the hopes of seeking commercial success.

“I don’t like being called a Kinetic artist because sometimes I am grouped with people who don’t have the same behaviour or attitude of research, someone whose work is similar to what I have done, but is only a careerist, who has developed a style just to sell or gain recognition, too wrapped up in the system,” he explains. “The problem with categorisations like these is that they encompass everything and anything. My approach is an attitude of research that has continued for a long time rather than one of becoming a monothematic artist, who has always done the same theme for 40 or 50 years. I analyse the situation of the artistic community as well. I thought the best was to start with myself. I have tried to change things by myself, not just theoretically.”

At 90 years old, Le Parc is as dynamic as ever, continuing to create daily in his light-filled atelier in Cachan, a Parisian suburb. A peek into the historical room packed full of 1960s works, sitting next to the overgrown courtyard, is like stepping inside a noisy arcade. Showing off his sharp, mischievous sense of humour, mechanical games are whirring, vibrating and rotating with plays of light and shadow, sound, movement and visual phenomenon sometimes producing optical illusions. A slatted box concealing a mechanism throws light into horizontal lines on the wall. Nearby, sculptures with reflective blades from his Displacement series fraction and multiply the image to form disconcerting optic effects as a viewer moves around them, while projected light bouncing off suspended mirrored discs creates myriad disco-ball reflections. Vibrating Image, Self-Portrait reveals his smiling face jumping in and out of focus on the wall thanks to a purposely shaky projector.

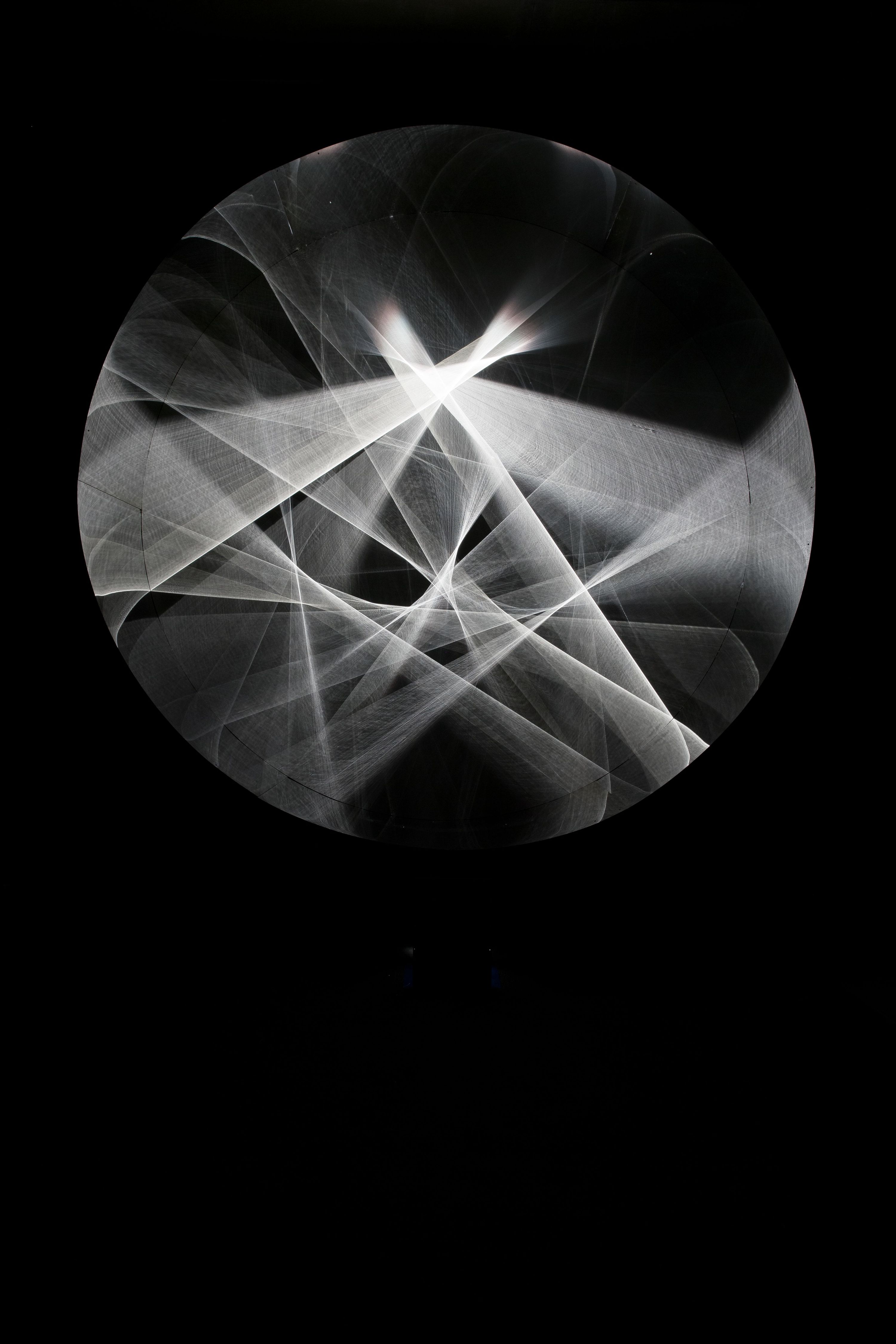

Throughout the decades, Le Parc’s wide-ranging work has spanned paintings on canvas, sculptures, works on paper and even virtual reality, as he now embraces digital art. A recent solo show at The Met Breuer in New York highlighted Form in Contortion over Weft with its long curvy strips undulating and merging with a black-and-white, vertical-striped background that was at once painting, sculpture and machine. At his first solo show in Asia at Galerie Perrotin in Hong Kong, Continual-Light-Cylinder, which he has been making since 1962, was affixed to the ceiling. Formed of wood, superimposed rotating metal discs, lamps, Plexiglas mirrors and motors scattering light rays in a circle within a pitch-black space, it gave viewers the impression of directly entering the hypnotic artwork.

The Long March mural is composed of 10 panels, each two square metres, displaying looping rainbow bands of colour that stretch from one panel to another in a continuous composition, like a dancing ribbon representing life’s unpredictable twists and turns. Then there are Le Parc’s Alchemy paintings, where multicoloured dots of pigment fan out across black or white backgrounds; large spherical mobile sculptures composed of hundreds of translucent Plexiglas squares are hung individually from the ceiling; and labyrinth installations featuring black-and-white striped floors, ceilings and walls with mirrored structures that disorient viewers and challenge their spatial perception.

The human experience lies at the centre of Le Parc’s immersive and interactive works, as opposed to art for a passive audience that is kept at a distance and forced to accept an artist’s proposals. An example of active audience participation is the motorised Ensemble of Surprise Movements, which establishes a connection with the viewer, who presses different buttons to set off spinning wheels, bouncing strips and shaking beads made of different materials, each moving part also creating a sound.

Le Parc says: “Participation was the beginning of the analysis with my friends, Francisco Sobrino, François Morellet and others, but there was someone who did not participate at all: the public who came to an exhibition, without making too much noise, only to receive things, but without any power. We began to do tests to find out if it was true that the public was unable to understand the art of its time. Our preoccupation from the start was the eye of the person looking, to have visual optical resonances. If we corrected the parameters a little, is the work more or less visual; does it produce more or less an optical reaction in the person looking at it? We started with the experience of the person looking and then, from there, participation was solicited little by little with other experiences until it was an active and reflexive participation. We realised that the public was very capable of appreciating what was currently being done or refusing the proposal. They looked and thought things over.”

Offering audiences novel ways to view art, Le Parc gives them a way to deal with uncertainty during times of political and social upheaval, as they emerge with a sense of optimism to overcome difficult situations. He says: “If there is a contact that is established between my proposals and viewers, and they leave my exhibition with a certain sense of optimism, that’s enough. Optimism may perhaps help them to better confront their problems.” As Le Parc himself states: “Optimismo siempre.”

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Art Issue, June 2019. To subscribe contact