Generation Gains

Seventh-generation shoemaker Markus Scheer explains how his family firm has navigated 200 years to remain at the very top of its craft.

After more than 200 years in business, Europe’s oldest shoemaker, Scheer, has entered a new era. But some things, like the secret to a good shoe, never change. Billionaire talks to Markus Scheer about how the company has survived and adapted over seven generations.

Billionaire: How did your ancestors come to be shoemakers for the rulers of the Habsburg empire?

Markus Scheer: In 1878, third-generation Rudolf Scheer was named shoemaker to the court for the Austro-Hungarian empire. After being awarded at the world exhibition in Vienna 1873 his work became more famous. Becoming a purveyor to the court was not easy. Lots of important people had to vouch for you and you weren’t allowed to have any debts or police records, for example. The title was later awarded to both of Rudolf’s sons, Carl and Edmund, in 1906, after Rudolf retired in 1905.

How has the firm managed to remain so elite — and moreover, survive — since it was founded in 1816 by Johann Scheer?

Surviving 200 years is a great privilege, but one must be careful not to let that weight get the better of you. My motto is, ‘fill your backpack half with the knowledge, the experience, the stories and tradition; the other half should be empty’. You want to stay open, stay hungry and create your own part of the legacy.

What were the most difficult parts in the history of Scheer?

The last 200 years we have faced almost every challenge you can think of. There were times when we lost large parts of our customer base, when the monarchy died, for example, or we lost nearly all our Jewish customers due to the Anschluss [annexation of Austria by Germany] in 1938. These were times when shoes where traded for sugar — or life. When fourth-generation Carl and Edmund Scheer died suddenly in the 1920s it was only due to the presence of Carl’s wife Auguste, and a famous artisan Josef, that the company survived until Auguste’s son Carl was old enough to take over. Yet all those challenges are valuable and an important part of our identity and craft today. We always made shoes.

How has bespoke shoemaking changed in the last two centuries?

The basic assumption — the core of our search to really understand feet — has not changed. Having said that, there have been big changes in the way people perceive shoes and feet. When the company started, walking was the primary way of moving and commuting, so your feet were very important, and so were good shoes. Knowledge of how to build exceptional shoes was hard to come by; you had to travel far and devote yourself to the craft entirely. Then orthopaedic knowledge and anatomical studies became state of the art. The human hand is still the most versatile and precise factor in making a pair of shoes.

Describe some of your shoes.

We made a pair for David Leppan [owner of Billionaire], a beautiful aubergine-coloured low shoe out of calf leather with Bordeaux alligator skin. We get a lot of comments about the shoe when people see it on our website. We also created an amazing pair of ankle boots out of shell cordovan and Japanese shironameshi leather [wild deer skin], which is extremely rare. One of our Japanese customers introduced us to the only man we know still making shironameshi leather in this traditional tanning way. He only uses salt and water, and the natural bacteria in the river to tan the hides.

What is the most expensive pair of shoes you have ever made?

A sting-ray slipper with diamond initials, for €85,000. Besides that, we made a pair of mountain boots out of 200-year-old Russia leather and a pump out of 100-year-old lizard skin. We have more than 10,000 leathers stored in our workshop. Some of them are nearly as old as we are. Endangered animals are, of course, off limit for us. In our philosophy we have a deep respect and appreciation for the materials we use.

How long do a pair of your shoes take to make?

Between 60-80 hours of manual work depending on the model and the complexity of the feet. I always take the measurements, carve the last [shoe mold] and cut the leather. Then one of our artisans works on the upper leather and another one builds the shoe from there, with my supervision.

How long does it take to train as a Scheer craftsperson?

Some people start as an apprentice, while some are skilled artisans already. But here we use the phrase of ‘becoming masterful’ in one’s field. That takes a good 10 years, from our experience.

What are your earliest memories of shoemaking?

My first memories are playing and pranking in the workshop with my grandfather. My school was near the workshop so I would just come by after school to eat with the family and artisans, and then hang around the workshop, playing and inhaling the atmosphere.

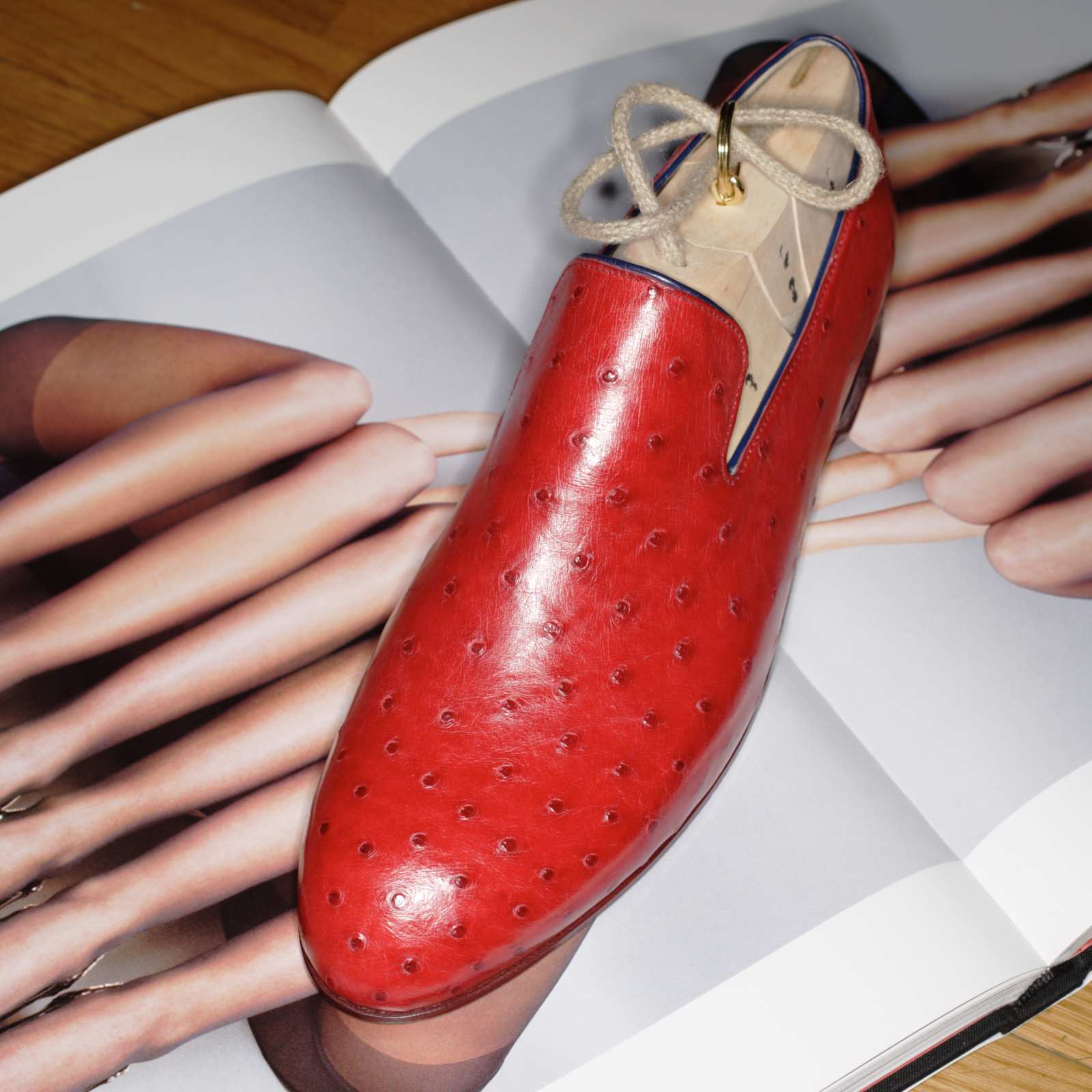

What is your personal favourite pair of shoes?

A clean red pair with orange stripes. It was one of the first models I designed and made on my own and therefore one of the starting points for me as an artisan.

What is the secret to a good pair of shoes?

It has to feel like walking on clouds on the inside, and to be as perfect as a sculpture on the outside.

How have you changed the business since you took over?

I took over the business in 2011 after nearly 20 years of training alongside my grandfather. I have modernised and grown the company and we now employ 20, including about eight shoemakers. At one point the workshop was about 16 shoemakers, but in the 1980s my grandfather slimmed down. Now we’re growing again.

If you had a time-traveling capsule, which time would interest you the most in the history of Scheer?

Definitely Rudolf’s period (1870-1890), when the craft reached its peak for the first time. At this point in history, style was over the top and craftsmanship was extremely well respected. I would have liked to walk through the streets then, with Rudolf showing me around. I feel it must have been an amazing time of opportunities and influences as a passionate artisan.