In Conversation With Gilbert & George

Seminal art duo Gilbert & George are seemingly not bothered what critics — or collectors — make of their work.

Gilbert Prousch and George Passmore have never hit it off with the art critics. Or, for that matter, with a lot of collectors. “They like the art, but they don’t want it on their walls,” chuckles Passmore. “But if they gave their cheque books to their children, well, they’d buy us. In that major struggle in the art world for supremacy — which is generally hostile to anyone doing anything different — all our pieces end up marginalised.”

Not that the duo, better known simply as Gilbert & George, seem that bothered. This year they’re opening their own foundation in East London (the part of the city with which they’re closely associated, and from which they rarely stray), in part, they say, because it allows them to show their bold art in a climate in which venues such as the Tate will not (although, in fact, among their many accolades, they’ve had a major retrospective at the Tate).

Gilbert & George met as sculpture undergraduates at art school in London and have recently celebrated 50 years together, both professionally and personally. Now both in their 70s they say that some 20 percent of their works sell, each around the £500,000 to £700,000 mark. And that’s enough for arguably art’s most famous living duo to do what they want to do: keep making art. “And we’re incredibly privileged in being able to do that. It’s incredible freedom,” says Passmore. “We answer to no one. When we started out, people said ‘oh, this will never last’. So, we had to prove them wrong. Now our biggest critics,” he says with another big smile, “are all old or dead.”

Indeed, for anyone who lives in the Spitalfields area of East London, their routine is as much part of public life as their own: they always rise at around 7am; have the same toast-and-marmalade breakfast in the same café; work in their home studio until around 6pm; and then take a taxi to the same Turkish restaurant, where they eat the same meal. They wear almost identical suits. It’s part of their proposition that together they’re ‘living sculptures’. One of their break-through works, from 1970, was standing on a podium together, singing the old music-hall favourite ‘Underneath the Arches’ for hours at a time. But it’s also, says the Italian-born Prousch, because the less they have to think about such matters, the more they’re free to think about art.

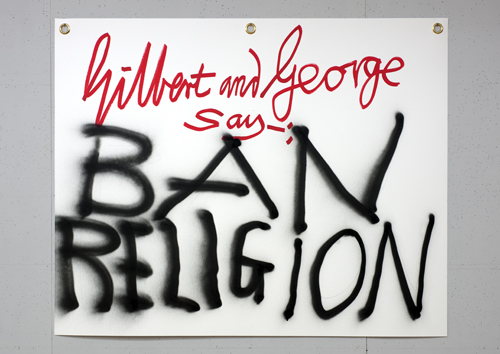

Gilbert & George

Gilbert & George say-: BAN RELIGION 1

2015

Water colour paper mounted on linen with three brass eyelets, red paint and black spray can paint 48 1/16 x 59 13/16 in. (122 x 152 cm)

© Gilbert & George. Photo © Gilbert & George Courtesy White Cube

“We’ve always kept to ourselves so that we could stay clear to our own vision of art. In the very early days, we were more part of the art scene. But we never really liked all those dinner parties. One day we made a conscious decision to just leave it behind us,” says Prousch. Both “ordinary conservatives”, Gilbert & George’s politics also set them in opposition to the stereotype that characterises most artists as left-wing. “Even if we travel, to install an exhibition, for example, it’s one day there and then straight back to what’s comfortable.”

And Gilbert & George are not short of opportunities to show their work. Early this year they had an exhibition at London’s White Cube gallery; then a vast retrospective at Luma Arles and another at Helsinki Art Museum; before being selected as 2019’s guest artists at the influential BRAFA art and antiques fair in Brussels. Here were seen the works for which they’ve become best known: large-scale, multi-panelled, stained-glass-like ‘visual sculptures’, based around photos they’ve taken locally and then manipulated, and typically featuring themselves.

They’re graphic, striking works, but they’re also confrontational. Pieces have at times included depictions of nudity, sexual acts and various bodily fluids, with titles such as Fuckosophy and the Naked Shit Pictures. These are intellectually challenging works, not shy of addressing issues such as patriotism, religion, racism, often long before such debates become mainstream.

And yet, anecdotally at least, Gilbert & George’s focus on what they call “the life force” has seen them maintain a high public regard, in part for being exemplars of an English eccentricity (that many in the UK might fear lost) and for their old-world gentlemanly ways. The latter may be a facet of their art persona, however, this lack of arty, rock ‘n’ roll wild-child rebelliousness has not stopped their readiness to kick against the pricks in their art.

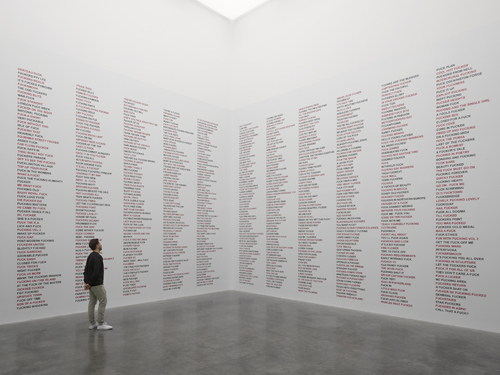

Gilbert & George

'THE BEARD PICTURES AND THEIR FUCKOSOPHY'

White Cube Bermondsey

22 November 2017 - 28 January 2018

© Gilbert & George. Photo © White Cube (Ben Westoby)

“The art world is generally hostile to anyone doing anything different,” says Passmore, “but we want our art to be visually powerful but also part of the world, which is why I think the public tends to like our work. There’s always been this huge gulf between critics and the public — there still is, not just in art, but in music and theatre. Most people who stop us in the street, and this happens all the time, have never been to an art gallery. But the art speaks to them, because it’s about life. The idea that our art is provocative is just a media invention. The public wants to be challenged. But content and meaning in art have become taboo. Look at a Degas now and critics won’t say, ‘well, it’s a picture of a ballet dancer’, but that it’s about the shapes made by the dancer’s legs, or some such absolute nonsense. Art has in some way become separated from the real world.”

It’s not just art that has become separated. Gilbert & George claim that with the passing years their art has grown better, more emotionally powerful, as a consequence of their own semi-hermitic life. “We see life in a different way because we don’t have friends and don’t go out. Our art is more modern for that,” argues Prousch. Indeed, their art is a kind of love story too, because they say they could not have succeeded in the way they have without each other.

“Working as a solo artist I could never have achieved what we have,” says Prousch. “The [artistic] ideas we had in the beginning, well, I wouldn’t have had the energy to fight the criticism, from the art world, the media. But making art together seemed like such an intense idea. In being together there’s so much more power. We’re alone together.”

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Art Issue, June 2019. To subscribe contact