"Like Everyday LSD"

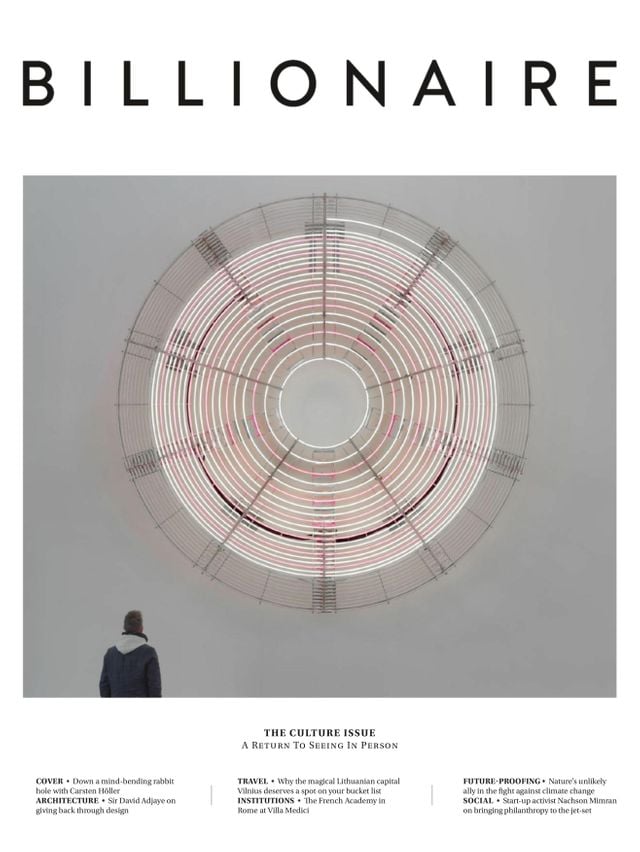

Escape into the trippy, occasionally terrifying, world of artist Carsten Höller.

“Consider the two extremes of joy and fear, pleasure and discomfort, madness and delight. Usually as humans we are somewhere in between. If we take away the in between we are left with the extremes, and it’s an interesting place.”

So says Carsten Höller part-scientist, part-artist, considered the Willy Wonka of the contemporary art world, while taking us through his new retrospective exhibition at Lisbon’s Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology (MAAT).

On show until end of February 2022, it is the five-year-old museum’s first single-artist show. It is easy to see why Beatrice Leanza, executive director of MAAT, chose Höller for this honour; he is everything you would want in an artist: exhilarating, experimental and a completely out-of-the-box thinker.

Our starting point is a huge billboard outside MAAT covered with 1,100 brightly flashing LED lightbulbs, simultaneously blinking at 7.8Hz, a frequency that supposedly activates brainwaves, accompanied by a rapid clicking sound. Looking at it, a sense of panic rises and the heart beats faster.

Höller calmly explains he has it at home in his living room in Stockholm where he has been fine-tuning it for years. “I’ve been exposing myself to this for many years.” I can’t imagine waking up to this brain-altering mechanism every day. “I’m an artist, I have to suffer,” he jokes in his dry Germanic way.

“You start to see things after a while, it makes you a bit high. It makes you hear the words you say to another person in a different way, and, in some way, it creates a sense of freedom. It is like everyday LSD,” adds Höller.

Next up, he leads us to a dark doorway called ‘Choices Corridor’ halfway through the show. An utterly pitch-black corridor winds back and forth in curves so we have to feel our way through the space. In the middle, unbeknown to us, the ‘blind’ viewer, the corridor separates into two sections, so that voices heard behind you ‘disappear’ acoustically.

“Suddenly you get a feeling of profound loneliness and über angst, deep anxiety that you might have felt as a child when you felt alone,” says Höller. As an extra-scary fillip, there is a door to a room in the middle where you are within thin walls, where you can feel the hands of others blindly feeling their way.

“It’s all about divisions as I think that is how we understand the world.” Höller shows us an enormous digital clock in pink and white, a collection of gold Fly Agaric mushrooms in a tank (which are said to induce hallucinations, especially when drunk in the urine of reindeer after they have consumed them) and a human-sized sphere suspended from the ceiling with blinking lights, inspired by the dimensions of a “modern day Vitruvian Man” (“I call it the suicide ball,” he adds, half-joking). It feels like I’ve disappeared down a rabbit hole into a rather sinister Wonderland.

He references his slides, the giant helix-like metal slide sculptures he installed all over the world from London to Copenhagen to Miami. With the slides, Höller hopes to recalibrate a person’s understanding and experience of their self. “The madness of a slide, that ‘voluptuous panic’, is a kind of joy, through that you find a certain freedom,” he explains. As with many of his pieces, this idea is that the viewer becomes part of the art.

We’ve stopped at a piece called Two Roaming Beds, which takes the form of two slowly moving robotic hospital beds fitted on a mechanism on wheels that moves around the room. Attached to the beds are a red or blue coloured crayon that draws lines on the floor as the bed rotates round the room. At the end of the exhibition, the idea is the floor will be covered in random squiggly lines. “Then in the morning you wake up and think, where have I been? We sleep on planes, trains and cars, there’s something about sleeping and moving.”

Visitors can rent a night in a moving bed that cannot be switched off, for €200 a night during the week and €300 on Fridays (the pass to explore the museum, solo, is included). You also get a toothbrush and pack of three tubes of differently coloured hallucinogenic toothpaste and an activator toothpaste, which Höller says can make you “dream like a man, dream like a woman, dream like a child, or you can mix all three together”. They also contain, he says, hallucinogenic plant extracts, some of which would be illegal if taken as a plant. But the leaves are burned to ashes in a pharmacy in Vienna and made into a paste, which can then be consumed legally, he says.

“I felt a bit like the painter in Provence who was mixing the colours on the palette. This is a modern version, and instead of a painting it is a dream,” he explains.

Although many of his works allude to drugs and shamanism, Höller himself is not a regular drug-taker. “Drugs are not useful, really, but they are super-interesting in that they show you how simply your everyday drug-free experience can be altered. I think it is almost like a must for an artist to at least experience that,” he said in an interview with The Guardian.

Höller was born in 1961 in Brussels, to German parents. He was very close to them, and later, in the name of art, recreated the scent of his mother and (then dead) father, by using items of their clothing. He invited viewers to sniff their smells at various exhibitions from 2017 as a ‘smell portrait’. “The people who sat on that bench also smelled like my mother and father. It was a little bit spooky.”

As a young man he earned a PhD in phytopathology (study of plant diseases) with a specialisation in chemical ecology. Although he never went to art school, he decided to dump science in favour of art. It was a process, he says, that happened “gradually, organically, over a long time”. (In fact, there is even a work in the MAAT exhibition he created in 1987, before he officially became an artist).

But science and experimentation colour everything Höller does, as well as the sense of the binary. “With Höller there is never just one way, it is always a dialectic. If it is about light, it is also about darkness,” says Vicente Todolí, curator of the show at MAAT and a long-time collaborator and friend of Höller’s. “Physicality is essential in the work of Höller, but also ambiguity, and putting into doubt the way you perceive the world,” he adds.

What informs Höller’s work the most, though, and perhaps the reason for his shift in career from scientist to artist, is his rejection of narrow rationality, his love of the random, the unpredictable, letting ourselves go and even experimenting on ourselves. After I leave, intrigued, I order a pack of the hallucinogenic toothpaste (€50). Now, like a painter, it is up to me to create the colour of my dreams.

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Culture Issue, Autumn 2021. To subscribe contact