Living History

What does it take to renovate one of London’s most meaningful historic Grade II-listed buildings?

When Sir Frank Baines built the Neoclassical Imperial Chemical House on the banks of the River Thames in the 1920s, he can scarcely have envisaged the army of skilled artisans that would be painstakingly restoring it, 100 years on.

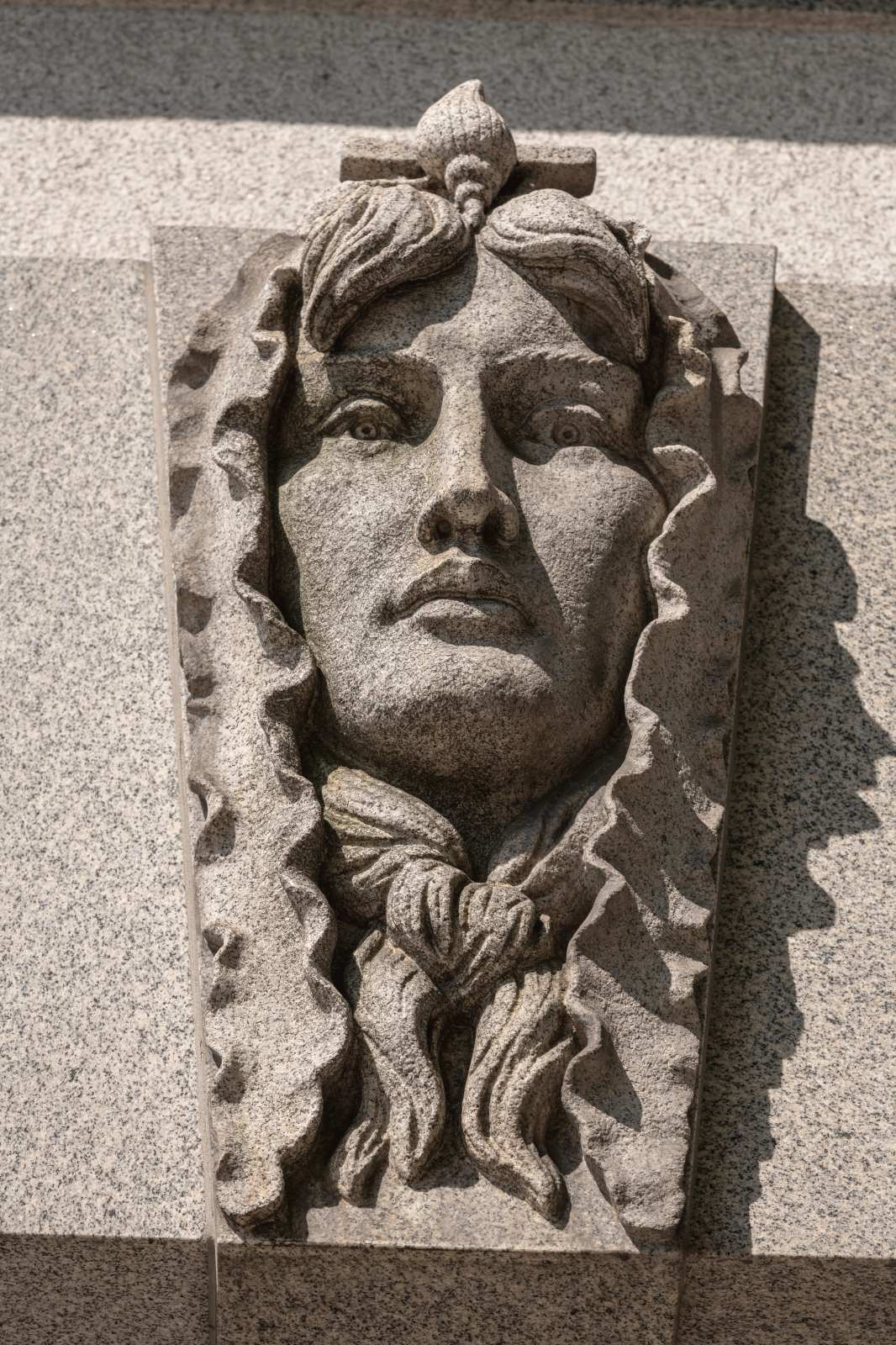

Initially built as the headquarters for Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI), at the time and, for much of its history, the largest manufacturer in Britain. Formerly known as Imperial Chemical House, the Neoclassical Portland stone building stood as a physical symbol of industrial innovation and global influence, decorated with busts of influential scientists that helped shape modern chemistry, including Alfred Nobel, founder of the Nobel Peace Prize.

At the time it cost nearly £1.8 million to build (£120 million in today’s terms) and it was highly innovative, being built faster than any other similar structure in the UK. It was also the first building in the world to be lit by artificial daylight and employees would breathe air freshened by an ozone plant and enjoy central heating and cooling in summer. Two 460ft artesian wells were sunk beneath the basement to create a private water supply and storage tanks to accommodate 80,000 gallons were put in the basement and on the roof.

But ICI lost its way and, in 1940, the fine building had been requisitioned by the government and occupied by the Board of Trade and Ministry of Aircraft Production. In recent years it has undergone another change of hands, this time to St Edward, a joint venture owned by M&G Investments and developer Berkeley, with a view to turning it into five luxury apartments called The Heritage Collection. Designed by Goddard Littlefair, St Edward commissioned master artisans to meticulously restore and, in some cases, delicately replicate, a catalogue of 1920s features.

ICI boardrooms and dining halls were transformed into grand entertaining spaces, while secretarial offices and postal messenger rooms have been repurposed as equally impressive bedrooms and bathrooms. Internally, intricately carved architraves, hand-cut timber panelling, ornate decorative ceiling plasterwork and cornicing, all subject to enhanced protection by Historic England, have been painstakingly repaired.

Sometimes this was harder than imagined. For example, the entrance to the building is flanked by two immense 20ft doors designed in 1927 by William Bateman Fagan, reminiscent of the celebrated bronze gates made by Lorenzo Ghiberti for the Baptistery in Florence. The two doors, each weighing 21 tons, are cast in bronze sprayed with Silveroid and each door is divided into six panels illustrating the progress of industry under the application and innovation of science.

These had to be renewed, however. Silveroid, a nickel-copper alloy used for watch casings in the 19th century fell into decline following the invention of stainless steel and is no longer made, so an alternative was required.

“We came up with a powder-coated aluminium, similar to Silveroid both in terms of performance and visual aesthetic, and this was subsequently adopted as the finish for new external metalwork,” says Kit Wedd, a heritage consultant and architectural historian who worked on the project.

Then there were the floors. Records of the building note the high numbers of people slipping over on the marble floors, and early on the marble was covered with linoleum given the safety hazard. When St Edward took on the building, the linoleum was removed and the original flooring uncovered. “Unfortunately, it was in such poor condition that it could not be retained but we restored the original pattern in new non-slippy marble,” says Wedd.

The walls have a decorative contrast dado and skirting detail in Green Purbeck Marble, which is a cretaceous limestone from a quarry on the Isle of Purbeck in Dorset; while the Italian stone used in entrance lobbies, decorative door architraves and columns is Perla Limestone, from a quarry in southern Albania near the village of Skrapar. The stone in the lobby was sourced from Italy, from the exact same quarry that the original stone came from in the 1920s and the Portland stone replacement colonnade on the sixth-floor terrace was also sourced from the original quarry in Portland.

Timber is used throughout and so was a major concern. To source the best timber match, joinery contractors first visually inspected the original panelling and took photographs, primarily focusing on colouration and grain, a range of the close matches were then put forward for approval with various tints and waxed finishes.

“We used European Oak to match the existing. The new was wire-brushed to open the grain and lime polished, the white lime polish sits recessed into the open grain achieving the visual match of the existing timber,” says Wedd.

The result is five stunning Grade II-listed homes priced from £18 million and above, scheduled for completion in the second half of 2022, one even including an original stone sculpture of the famous chemist Charles Sargeant. For a daily dose of living history, one can hardly find better than that.