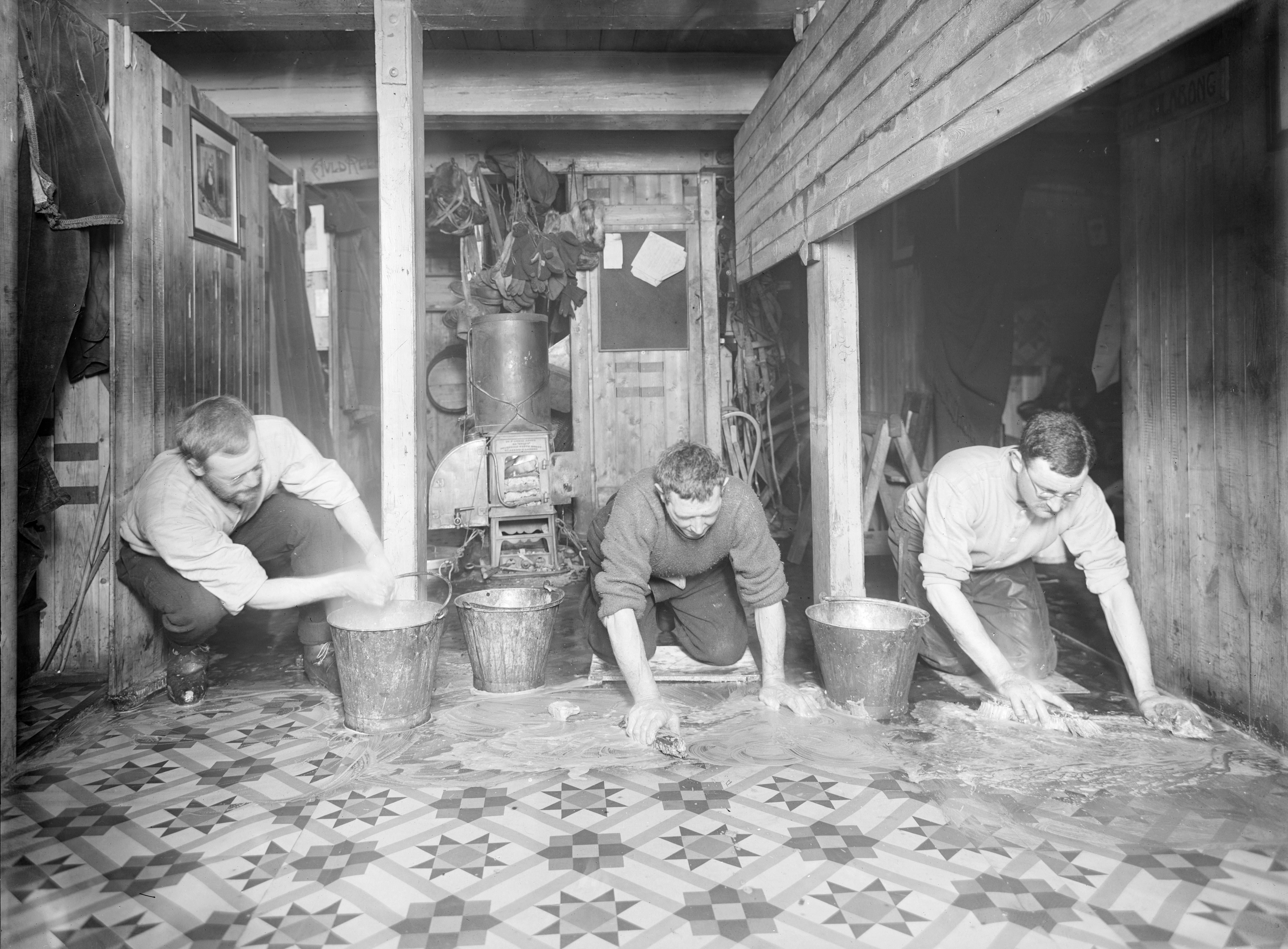

Prints From Shackleton's Endurance Expedition

A century on from Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance expedition, platinum photographs are available for one more week at Hong Kong-based travel company, Jacada.

The Endurance stuck in the ice (c) Frank Hurley

Alexandra Shackleton never knew her grandfather, arguably the most famous polar explorer in history. Sir Ernest Shackleton died of a heart attack when her father was only 10 years old. But the family is intimately connected with his story of leadership and courage.

“I grew up with this one at home, and as a child I used to ask, ‘what happened to the dogs?’ and the grown-ups wouldn’t tell me for ages,” recalls Alexandra, pointing to a photo taken by legendary photographer Frank Hurley, who accompanied Sir Ernest Shackleton and his men on their Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition from 1914 to 1917, during the heroic age of Antarctic exploration.

Like many polar exhibitions of that era, of course, the men were forced to eat their huskies when they were stranded, starving, on the ice.

The story of Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance expedition is a legendary one. He kept his whole team together without losing a single life, despite being stranded in extreme conditions for over two years. His leadership skills are still lauded today and the ‘Shackleton Method’ (staying calm in a crisis, knowing your men, and other essential traits) is taught at institutions from Exeter University to NASA.

After having successfully led two polar expeditions in the early 20th century, Shackleton set his sights on crossing the South Pole, from sea to sea. Shortly after he and 28 crew members set off from the whaling station at Grytviken on the island of South Georgia, the Endurance became trapped in pack ice. After being stranded for nine months, Shackleton and his crew were forced to evacuate as their ship was being crushed by the ice. They set up camp on the floating ice for five months until Shackleton decided there was no rescue coming, and they had to find help or face starvation. Shackleton and five crew members set off on a journey of 1,300km in an open-top boat with no sailing equipment through the Drake Passage, considered the most tumultuous patch of ocean in the world.

After eventually coming to land in South Georgia, Shackleton led his team over an unchartered mountain range without maps or mountaineering gear. They eventually reached a whaling station and he organised a rescue party for the remaining stranded men, which only succeeded on the fourth attempt due to ice and weather.

It’s no surprise that in his 1956 address to the British Association, Sir Raymond Priestly, one of his contemporaries, said: “[Robert] Scott for scientific method, [Roald] Amundsen for speed and efficiency but when disaster strikes, and all hope is gone, get down on your knees and pray for Shackleton.”

The incredible journey is brought to life thanks to photographer Frank Hurley, who was a member of the expedition and miraculously able to salvage 150 of the best prints, even though over 400 were destroyed. They create an essential pictorial record of the incredible story. Some are now available to purchase as platinum prints, with all proceeds going to the Royal Geographic Society. Alexandra Shackleton describes Hurley as “a genius of a photographer”.

In Hurley’s diary, dated 2 November 1915, as the Endurance was sinking beneath the Weddell Sea, Hurley described: “During the day I hacked through the thick walls of the refrigerator to retrieve the negatives stored therein. They were located beneath 4ft of mushy ice and, by stripping to the waist and diving under, I hauled them out. Fortunately, they are soldered up in double tin linings, so I am hopeful they may not have suffered by their submersion.”

Alexandra has long been a flagbearer of her grandfather’s legend, representing him at global exhibitions of Hurley’s Endurance images. The roaming ‘Enduring Eye’ exhibition, she says, has received over 280,000 visitors alone.

“Shackleton once set down the qualities he thought a polar explorer should have,” she relates at a launch of the prints at Jacada Travel, a Hong Kong-based travel curator. “First, he had optimism; he never looked back, he was pragmatic. Second, patience. Patience enough to lie in a tent with a blizzard howling outside and knowing that the wind would abate at some point. Third, imagination, to remember why you’re there, it’s a great adventure. And last of all, you might have thought he’d put courage as the first. But he said, no, no man in the polar regions needs courage more than a man in ordinary life. In ordinary life a man needs courage because his friends are trying to take what Shackleton describes as the ‘rose-leafed path’ and make him do the wrong thing. He said that takes true courage.”

But Alexandra believes that he had courage in spades, as well as many other good qualities. “He was a nice man, he loved his men and they loved him. He was good company, you know, Irish.

“He was a great leader, but atypical of leaders 100 years ago, because it wasn’t usual then to do all the menial jobs. Although he expected his men to obey him, they knew he was totally committed to them, and the expedition,” she says.

But Alexandra says the thing that makes her most proud of her ancestor is that he turned his back on being the first man to the South Pole, because his men would have died. “It is one of the great decisions in polar history. He brought triumph out of disaster.

“He simply said in his diary, ‘a man must set himself to a new mark, directly when the old one goes. And the new mark is to bring every member of the expedition home alive’.”

As well as through Jacada Travel, prints are available for purchase through RGS London. For matters regarding print purchases, please contact