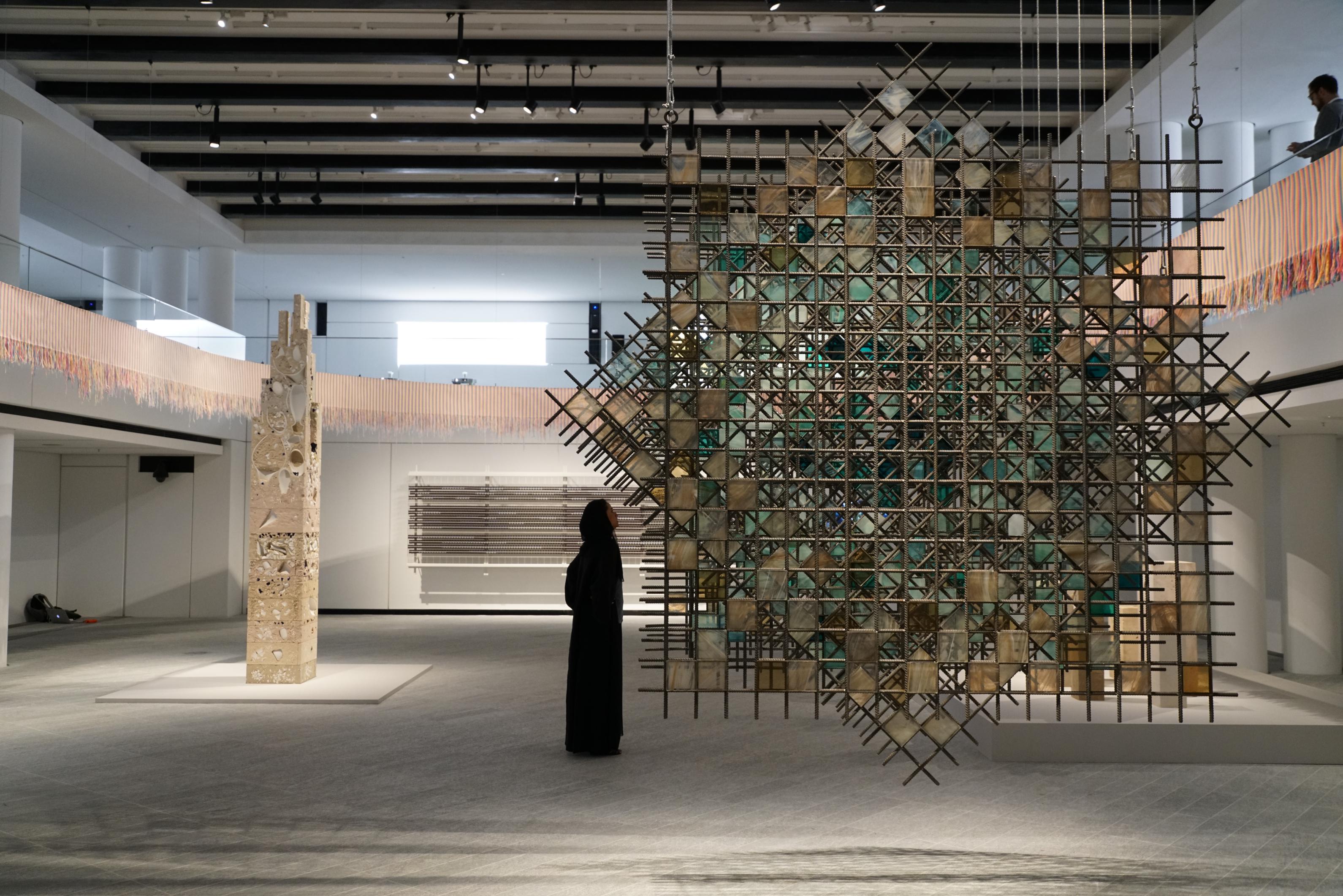

Inside The Louvre Abu Dhabi

While the Louvre Abu Dhabi is housed in a beautiful and provocative structure, it is its cross-cultural curation that proves to the real head-turner.

Squatting next to the towering, mirrored skyscrapers that line the Abu Dhabi seafront, the Louvre Abu Dhabi, a billion-dollar ode to world culture, seems uncharacteristically modest given its name and location.

But from the moment you step out of the brilliant Emirati sunshine and inside building, it becomes clear that this multi-national project is extraordinary in more ways than one.

Renowned French architect Jean Nouvel designed the building, which opened earlier this month and is allowed to share a name and artworks with the iconic Parisian museum for the next 20 years. This is the result of a US$800 million deal — a first for any art institution outside of France.

From the outside, the low-slung dome looks like a hovering spacecraft, weightless with no obvious means of support other than a cluster of white, cubed buildings built next to the flat Gulf sea.

But once you step inside Nouvel’s other-worldly structure, it becomes clear that the 180m-wide dome is self-supporting, open to the air on all sides and constructed from a honeycomb of stainless steel. This filters the sunshine into shafts of light, creating lattice-like shapes across the museum floor.

But while the structure is beautiful and provocative, it is the curation that is notably unique for a world-class museum. The entire institution is a meditation on universal human values, allowing the curators to celebrate the modern Arab world and the region’s multicultural heritage, while exploring the emotions that bind all human beings together.

“Categorising objects based on geographical origins or material actually stems from 16th century Europe,” says curator Mohamed Abdulla Al Mansoori, who walks me through the museum one hot November morning. “The Louvre Abu Dhabi is unique in that it is a 21st century institution that looks at the relationship between cultures and the development of shared themes, technique and aesthetics.”

And, after decades of museum-going, this feels almost revolutionary to me. We are all accustomed to curation that divides work by classically defined art-history movements, but the Louvre Abu Dhabi has chosen a ‘chrono-thematic’ arrangement instead.

This can lead to highly unlikely pairings. For example, one room explores the nature of motherhood, in which Renaissance paintings of Madonna and the infant Jesus are hung next to Ancient Egyptian depictions of the goddess Isis and her son Horus, alongside maternity figures of the Yombe culture in the Dominican Republic.

Other displays are philosophical, focusing on academic theories such as pictorial perspective. The artwork is then used to illustrate the contrast between Europe, where man was at the centre of philosophy and through whom the world was viewed; and the Middle East, where a divine or heavenly perspective was projected onto the world.

Inside the Louvre Abu Dhabi (c) Greg Garay

Overall, the rooms range from the easily comprehensible, (depictions of Sumerian priest kings next to the pharaohs of Egypt) to the confusing — Leonardo da Vinci’s 15th-century portrait of a woman reading, with some floral Iznik tiles from Turkey of a century or so later.

And if you aren’t an art-history graduate, you will need an audio guide to understand some of the more complex groupings. But as we proceed through the cavernous rooms, it becomes clear that by stripping away the boundaries, all the works are displayed in an entirely new context.

“Louvre Abu Dhabi’s new narrative is shown not only in our universal arrangement of objects but also in our interpretation of these objects in relation to one another, reflecting today’s globalised world,” says Al Mansoori.

“I believe the similarities outweigh the difference s between cultures and people who really all stem from a shared origin or heritage.

We are highlighting these similarities and shared values in our museum — it is an absolutely interesting view of human history that must be considered in other cultural institutions.”

This exploration of universality feels particularly important in our era of rising Western nationalism. But, on a more specific level, it has allowed the new Louvre to distinguish itself from its iconic namesake and immediately step out of its long-reaching shadow.

“The two museums are completely different,” says Al Mansoori. “Louvre Abu Dhabi has a new approach to the story of human history that differs greatly from the traditional and somewhat segmented museography used by other museums. The similarities really stop at the name.”

But proving there is no ill will between the two, the museum is currently running an exhibition entitled, ‘From One Louvre to Another’, on the inauguration of the Musée du Louvre in Paris in 1793. This will include an overview of the Parisian art scene of the era, with paintings and ornate pieces of furniture from King Louis XIV’s personal collection in Versailles also on display.

This peek into Paris’ golden age will run until late April, after which ‘The World in Spheres’ will take its place. This far-reaching exhibition will look at the world from antiquity to the present day through a collection of exquisite painted globes, including those created by philosophers in Ancient Greece and 16th century Muslim astronomers who were at the forefront of celestial research.

“See humanity in a new light.” Before I arrived, I thought the tag-line for the Louvre Abu Dhabi was slightly overblown. But it might just be right.

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Ideas issue, March 2018. To subscribe contact