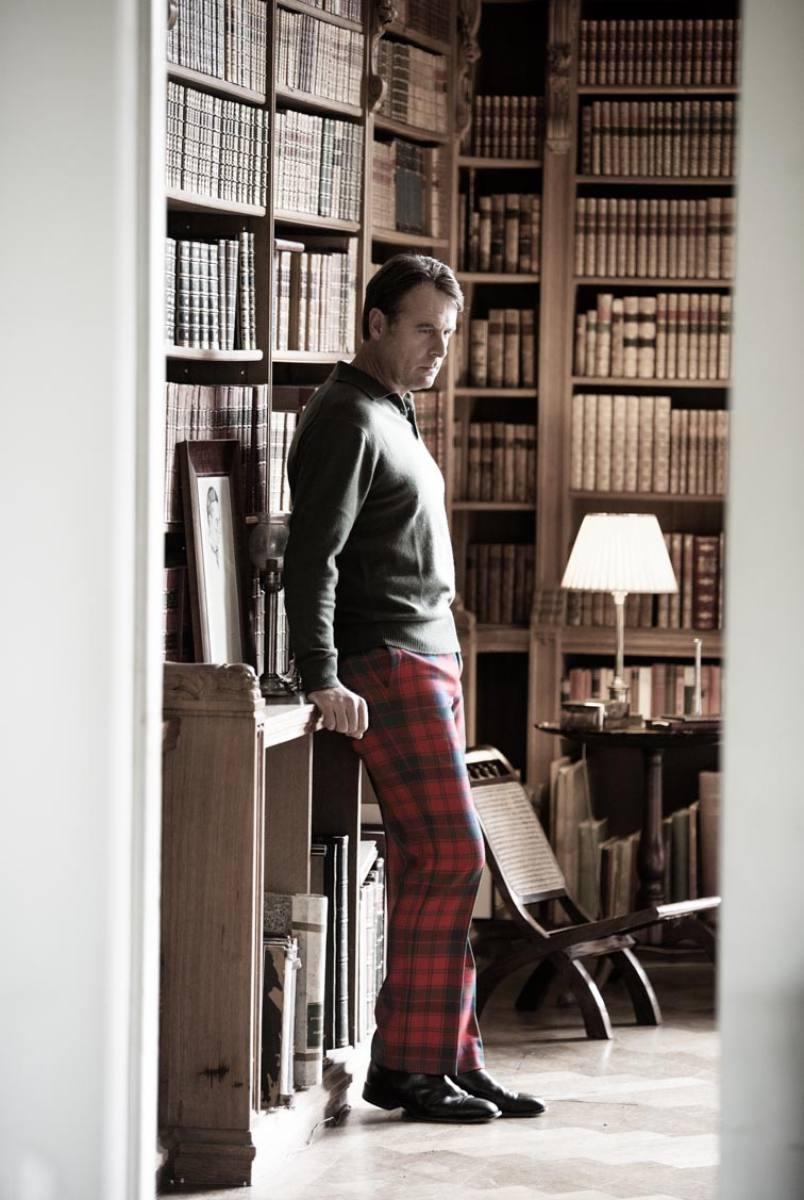

Time For Tartan

DC Dalgliesh, a hand-maker of Tartan, seeks to retain tradition whilst moving with the times.

It’s an unlikely club that contains the Dalai Lama; Neil Armstrong; Johnnie Walker; Google; Nelson Mandela; the Kings of Leon; and Queen Elizabeth II. But each has its own tartan, that characteristically Scottish pattern of woollen fabric found in kilts, of course, but also in home furnishings and fashion. Vivienne Westwood, Celine and Katharine Hamnett, as well as younger designers Ashley Williams and Charles Jeffrey, have experimented with the distinctive plaid. What’s more, they’ve all had their bespoke fabrics made by one company: DC Dalgliesh of Selkirk, the world’s last hand-maker of tartan cloths.

Dalgliesh last year celebrated its 70th anniversary (it was founded by tartan expert Dixon Dalgliesh to offer a superior-quality tartan). However, it was facing closure not so long ago. “It was going the same way of so many makers; suffering from the manufacturing of cheap tartans out of China, in particular,” says Nick Fiddes, company managing director, who led the purchase of the company by Scotweb. Fiddes saw the opportunity to make tartan at volume (up to 400m of fabric at a time, for organisations such as the British Armed Forces) but also to push harder on creativity and the hand-making of very small runs.

“The manufacture of tartan can be a mix of the modern and the traditional; and we’re now the only maker with the old and much slower shuttle looms, which make for a much higher-quality tartan, and with the capability to make a tartan with a selvedge,” says Fiddes. “But you do have to be more progressive about what tartan can be too. When we stepped in we weren’t from a dyed-in-the-wool tartan background, so wanted to know, for example, why certain colours weren’t being used. That’s down to tradition. But while we don’t want to lose hold of traditions, tartan manufacture has to move with the times. It should be a vibrant culture.”

The diversity of DC Dalgliesh’s clients speaks to just that: corporate interests such as Canadian airline Westjet; signature tartans designed for whole cities (Kraków recently commissioned its own tartan); film work (it supplied tartan cloths for the making of Netflix’s The Crown); and those used throughout the Gleneagles Hotel. Golfers are represented by the late Arnold Palmer, who had his own tartan. Most are careful to have selected colours of some personal significance (although the idea that certain colours used in tartans have specific meanings is a modern one), with others even having a special number reflected in the weave via the thread count.

Few of those seeking their own tartan are Scottish. Indeed, while tartan has been widely associated with Scotland since the 16th century and was used to distinguish the inhabitants of different regions of Scotland since the early 19th century, tartan is believed to have roots with Celtic peoples more generally back to the 6th century BC.

“The idea that you must be Scottish to have your own tartan is really a big myth too,” explains Fiddes. “There are some conventions, of course. It’s not the done thing to use the Queen’s Balmoral tartan, for example, unless you’re the Queen’s personal piper. But tartan is historically inclusive and has been right back to the old clan system. It wasn’t just the MacDonalds who wore the MacDonald tartan.”

That’s MacDonalds, not McDonald’s, by the way, although it would be small surprise if the fast-food giant had its own tartan soon enough. After all, tartan is enjoying something of a revival: current autumn/winter collections from Balenciaga, Dolce & Gabbana, Louis Vuitton, Calvin Klein and Isabel Marant, Stella McCartney, Hermès and Chloé all featured plaids. However, this is a revival that tartan manufacturers have seen before. “It’s become a standing joke with us when someone in the fashion industry announces that ‘tartan is back’,” chuckles Fiddes. “There seems to be a constant rediscovery of tartan by designers and has been since the 1960s.”

He does, however, stress a distinction between a run-of-the-mill checked fabric and a tartan. “The difference is that a tartan, traditionally, is associated with a certain place, or event, or people,” says Fiddes. “It’s the fact that it has a story associated with it that makes it stand apart and makes each tartan unique.”

A royal connection underscores tartan too. Remarkably, the wearing of tartan was once banned under the Dress Act 1746, which stated that to do so was an act of Scottish rebellion. So when, in 1822, King George IV visited Scotland, the first visit of a reigning monarch in almost two centuries, it was to lead to something of a rapprochement with the pattern, if not an outright craze for it. The bright-red Royal Stewart tartan that came out of that visit remains the most popular of all tartans, and the royal family, notably Prince Charles, has been enthusiastic wearers of it since.

“There’s a reason why some people have referred to tartan as being Scotland’s gift to the world,” says Fiddes, “because it has that association with history, heritage and community, while also being visible at 50 paces. These days it’s regarded more as simply being a beautiful fabric with great use of colour and, like a whisky blender, we often think of finding the right tones for a tartan to be a similar process. But a tartan still resonates in telling people who you are. That’s why people still like the idea of having a tartan that is theirs.”