Striking The Right Note

Glyndebourne is a global operatic phenomenon, which, under the helm of its third-generation director, has succeeded in staying relevant without “dumbing down”.

It’s been a torrid few years for world opera houses. Many are reliant on government funds and have had budgets progressively slashed; five years ago, the New York City Opera filed for bankruptcy; while the Baltimore, Mercury, Connecticut and Cleveland opera houses have all shut down. In Europe, Italy’s beloved Petruzzelli has cancelled several productions due to lack of funds, while even the famous La Scala has reportedly been struggling to make ends meet.

Not only is obtaining finance tough but ticket sales are dropping. Some cite opera’s failure to stay relevant to a younger audience, alienating many through price point and putative elitism. Theatres that survive are those able to tap a new vein of theatre goers without ‘dumbing down’ and alienating loyal ticket holders.

One such institution is Glyndebourne, an English country manor with an opera house in its garden. In the 1930s, the owner of the house, John Christie, and his Canadian soprano wife, hosted regular amateur opera evenings in their sitting room. Their mutual passion for music (and a conviction that the British were in dire need of some culture) led them to build a 300-seat auditorium in their garden, growing their love of opera beyond a hobby.

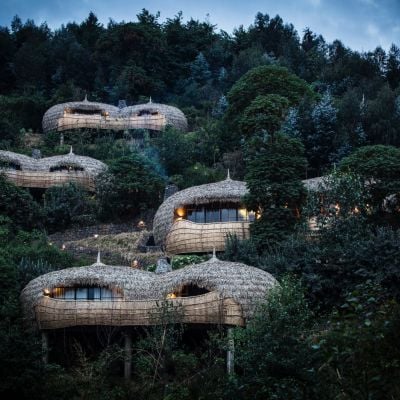

Almost a century later and Glyndebourne’s opera programme is stronger than ever. Every summer, it welcomes 50,000 attendees to its vibrant gardens for its famous festival, between the end of May and August. Guests dress up formally for an elegant picnic in the grounds, which range from an impeccable rose garden and clipped hedges, splendid herbaceous borders, a lush tropical garden, to smooth lawns reaching down to the lake, studded with large trees giving shade. A wilder area on the other side of the lake allows more adventurous opera-goers to set up their tables in knee-high grass and greater seclusion under beautiful mature beech trees. No pavilions or umbrellas are allowed, so the views are sweeping and unspoilt.

After dinner, guests amass to the storied red-brick opera house to marvel at world-class productions, ranging from Madame Butterfly to Die Zauberflöte to Faust. Performances are always original, wild and electrifying, a Handel oratorio combined with Monty Python’s Flying Circus. In this year’s performance of Saul, the curtain raised to reveal a huge, severed head of Goliath on stage covered in black ash. In the next scene, the famous Glyndebourne chorus danced and disported themselves on tables laden with the makings of a sumptuous feast: wild boars, swans, huge carp, cornucopias of fruit and massive, extravagant, flower arrangements. This was followed by the dark aftermath of battle when the whole ash-covered stage was carpeted in candles that were extinguished one by one.

For the last 18 years the opera house has been led by Gus Christie, grandson of John Christie. Gus was born at the house and raised on opera, “an amazing childhood surrounded by music and artists, and strange people coming in and out of the house”.

As a young man, his father suggested to Gus that he “might be quite good at running” Glyndebourne. He was daunted to say the least.

“I thought ‘oh shit’, it freaked the hell out of me,” he recalls over the phone from the 600-year-old house in East Sussex. “After all, it’s a national institution and a life-long commitment.” Gus mulled the situation over for a few years. “It took me until I was 30 to decide I wanted to do it. Inheritance is not an easy pill. You don’t feel you’ve earned it. But I’m really glad I did.”

Glyndebourne is bucking the trend by being the only opera season in the UK to be almost entirely donor- and member-funded. It turns over £30 million annually, two-thirds of which comes from box-office sales, the rest mainly from donors and members. It sells most of its 50,000 tickets to members, while 20 percent are available to the public at an average price of £175, ranging up to £250.

The price — not to mention the reputation — can be intimidating, Gus admits, although the venue is finding ways around that. There is a “natural tension” between maintaining loyalty among his older membership group and enticing a new audience. “We’re trying to engage tomorrow’s audience and it’s challenging. The word ‘opera’ conjures up something your parents or grandparents go to. It’s considered elitist.”

Four years ago, Glyndebourne began an under-30 scheme, selling seats for £30 for those aged 30 and under. It’s been very successful, says Gus, and to date the venue has sold 7,000 tickets to under-30s each summer. “We are breaking down barriers to get people to experience [opera] because it’s a magical, life-enhancing, art. The older members understand the importance of this and support us,” he adds.

Glyndebourne was also the first opera house to run live screenings in cinemas 16 years ago. Today its productions can be seen in 130 cinemas around the country. It also live streams its six operas every summer on the Daily Telegraph website, where people can access them for free. “People all around the world are watching operas from Glyndebourne,” says Gus.

Trying to lure a younger audience was attempted less successfully by Glyndebourne’s peer, the English National Opera, with its ‘Undress for the Opera’ campaign. Attendees were encouraged to wear jeans and trainers and enjoy cocktail and beer promotions at a ‘club-style’ bar. It raised many eyebrows in the industry, including those of Gus, who still encourages his patrons to wear formal dress. “It was complete nonsense,” he recalls.

“You can’t dumb down. Young people, people of any age, enjoy dressing up rather than wearing jeans and a T-shirt. You make an effort yourself to go to something where people have made a lot of effort; you feel part of the theatre.”

As well as achieving a fragile balance between old and new, Glyndebourne’s other great success has been to consistently attract the best talent. “I think there’s a sort of an ethos here and it’s about discovering young talent: in singing, conducting and directing, across the board. Our chorus is second to none. We hire these young enthusiastic singers from all over the world and they’re given the chance to shine if they work hard,” says Gus. Attention to detail, hiring the best prop makers, costume producers, technicians and so on, all goes into it. You can never sit on your laurels, he cautions.

“We try to uphold my grandparents’ motto: ‘Not the best we can do but the best that can be done, anywhere.’ So, we have a very high bar,” says Gus. “From the beginning, my grandfather [John Christie] was fortunate to get the directors he did on board and that set the standard for the musical and artistic standards to which we aspire today.

“When the curtain goes down at the end of the evening and there is a hushed silence, you know you’ve really captivated the audience.”

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Giving Issue, December 2018. To subscribe contact