Atkinsons: Heaven Scent

Once Britain’s pre-eminent maker of fragrances, Atkinsons is making a comeback in the venerable surroundings of London’s Mayfair.

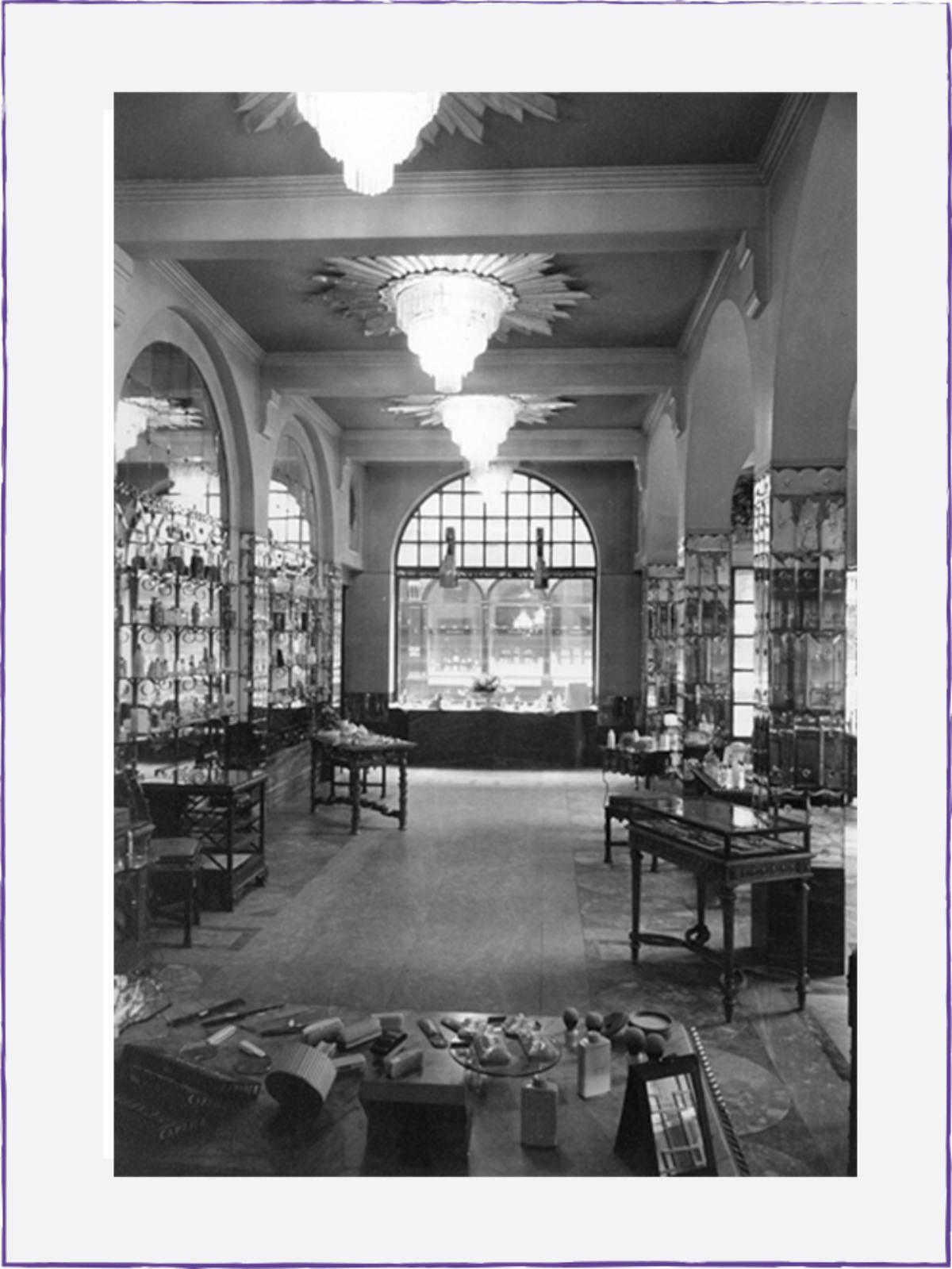

Walk along Burlington Gardens, in London’s Mayfair, to the corner with Old Bond Street and, once it’s pointed out to you, the fascia of one building may strike you as an especially intriguing dip in the city’s retail past. There stands some Gothic Revival architecture built in 1926, the ornate, colourful Arts and Crafts stone work detailing the three Nativity kings who delivered frankincense and myrrh. That’s revealing, because this overlooked, department-store-sized building was the headquarters for Atkinsons.

The fact that this name will be lost to most (and the building overlooked by most) is a shame, especially for anyone interested in the history of fragrance, because Atkinsons was once Britain’s pre-eminent maker of fragrances. One James Atkinson launched the company back in 1799. Such was Atkinson’s success that he could soon count the dandy Beau Brummell and the Prince Regent, Napoleon, the Duke of Wellington and Horatio Nelson, as well as Queen Victoria, Sandra Bernhard and TE Lawrence among the company’s regulars. Clearly, enmity in life did not stop certain men sharing the same affection for their perfumer. And now the company is back, with a store as close as possible to the original, on Burlington Arcade.

“The fragrance industry at the top end is all about niche products now, appealing to a limited number of people, perhaps, but people who want craftsmanship, with history and a story. And Atkinsons has so much of that,” says Dino Pace, CEO of Perfume Holding, owners of the Atkinsons brand, which has unsuccessfully passed through several hands since the store closed during the Second World War and the original company effectively fell into decline over the following decade. “Deciding to go back to the roots of the company is romantic, of course, but there’s also a sound business decision there too.”

Going back to the roots is certainly what the new owners are doing with Atkinsons. Its most obvious expression, the store, has been conceptualised by designer Christopher Jenner as a neo-Georgian English gentlemen’s club, with some chinoiserie details lifted from the original store, entirely bespoke and made by English craftspeople. Set over three floors, with a lounge area for one-to-one fragrance consultations, there is a traditional barber in the basement, with the main sales area arranged as a contemporary fragrance bar. Further stores are set to open in Moscow and Dubai.

“Getting as close to the early 20th century original building was absolutely on purpose,” says Pace. “Burlington Arcade has recently become something of a ‘fragrance alley’ [Roja Parfums, Chanel, Penhaligon’s, Frédéric Malle and True Grace all have perfume shops on the famed covered shopping street]. But we’re here for a deeper reason.” The location of the shop places it “right at the heart of that English sartorial tradition”, as Pace puts it. “And, while it may be Italian-owned now, Atkinsons will be run out of the UK by British people. That’s important to ensure the brand retains its British sensibility, which does seem to be so in demand around the world.” He adds: “Like so many British creative enterprises, from fashion to music, Atkinsons will be all British except the ownership”.

That sensibility’s famed quirkiness might not, however, perhaps match that of Atkinson himself. One of his first products was a rose-scented bear’s grease balm: then, and up until the 1910s, a popular treatment for men for hair loss (the 17th century thinking being that, since bears were hairy, smeared over the right places, their fat, mixed with beef marrow and a fragrance to mask the resulting unpleasant whiff, would facilitate in the re-growth of human hair). To advertise his product, Atkinson, would tie a bear up outside the shop. Such was the early association between Atkinsons and bear’s grease (largely because, the company claimed, its product was made with “genuine” bear’s fat, and not the pig fat used by rival manufacturers) that a chained bear became the company’s early logo. Fortunately, Atkinsons reputation as a perfumer soon surpassed that of his more ursine preparations.

But these fragrances also stood out for taking a distinctively English approach to eau de colognes: they were as fresh as fragrances then coming out of continental Europe, but they were also spicier and stronger, with a longer trail, all characteristics retained in the new interpretations. For these, the ingredients are, where possible, sourced in Britain or its historic colonies; right down, for example, to favouring neroli grown in the Scilly Isles over the more commonplace variety sourced from around the Mediterranean.

The fragrances themselves are effectively all unisex, with sales split roughly 50/50 between men and women. The 24-strong collection includes classics (rose, cedar and lavender-based fragrances); some eight heritage fragrances that use original recipes; as well as modern fragrances designed by leading noses, among them Karine Dubreuil, Benoist Lapouza and Christine Nagel (now the in-house perfumer at Hermès). Each year the company will launch a limited-edition fragrance of some 1,799 bottles, the latest being called 41 Burlington Arcade.

Pace argues that Atkinsons fragrances, both the 18th and 19th century concoctions, as well as the new styles, are sufficiently distinctive to not be for everyone. The main note in 41 Burlington Arcade, for instance, is liquorice. “But I think that’s one definition of niche now, something that polarises,” he says, quite happy about the idea. “In a way, the more you have people who don’t like what you do, the better; as long as there are enough who do like it, of course...”

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Discovery Issue, September 2018. To subscribe contact