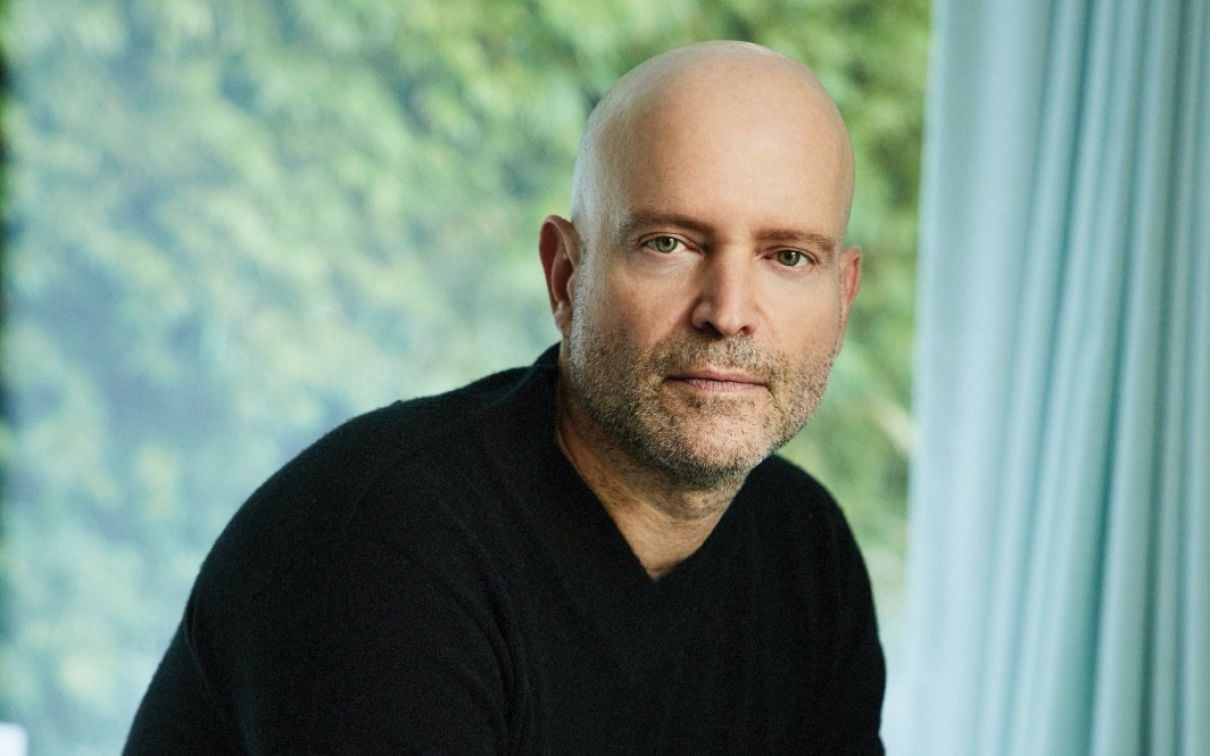

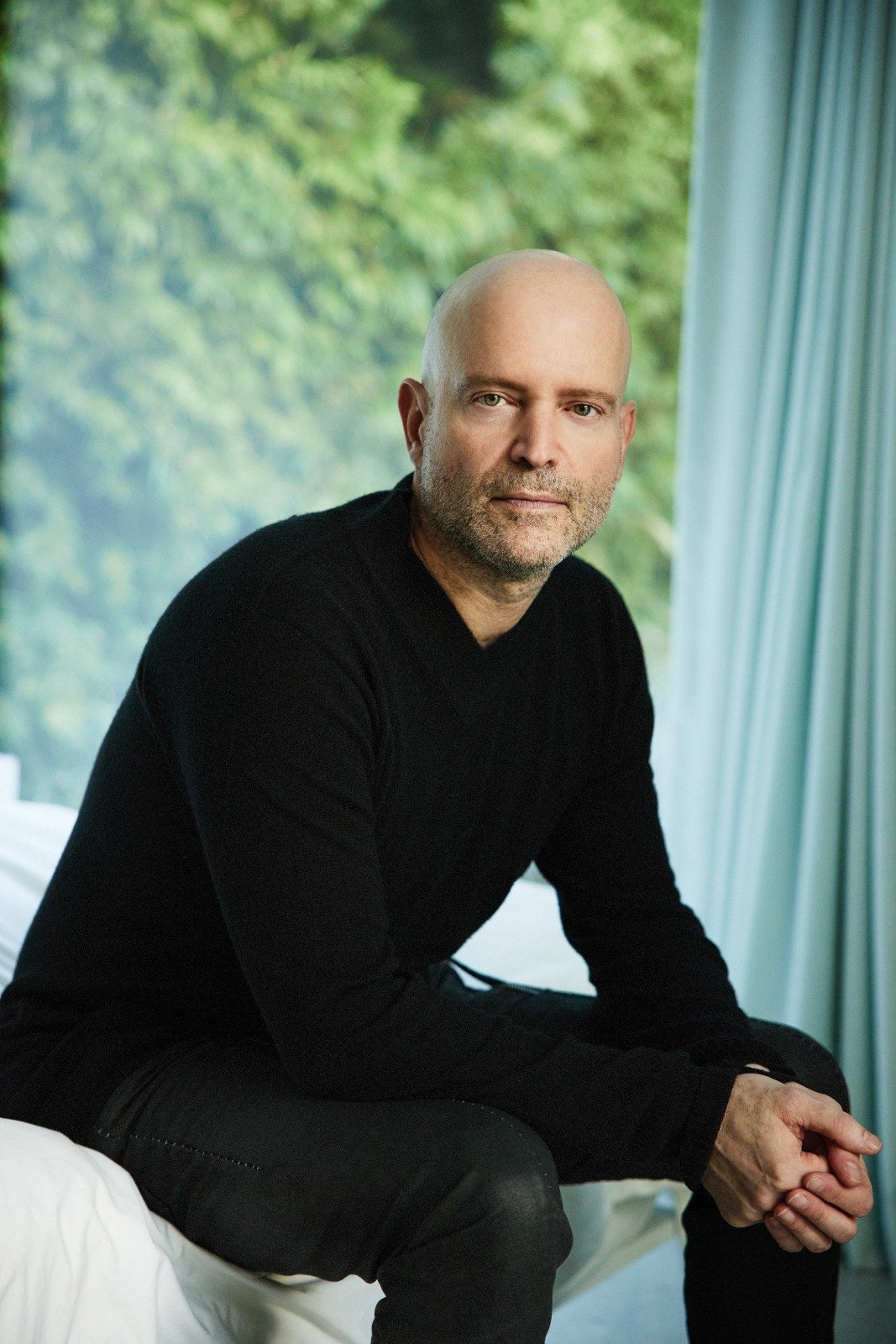

The Story-Tellers

Film-maker Marc Forster believes that cinema and theatrical film can play a healing role in society.

It seems ironic that one of the most accoladed film-makers of our generation grew up without a TV. Instead, he would entertain himself for hours in the forest, playing with imaginary characters, scenarios and costumes, which, much later, would form the inspiration for the character of JM Barrie in Finding Neverland. It was this upbringing perhaps that meant Marc Forster’s first visit to the local cinema — to see Apocalypse Now — in a small mountain town near Davos, Switzerland, left such a deep impression on him.

“I was in a dream-state, I felt I was transformed. At that moment I became obsessed with movies,” he recalls, when we meet at the Warner Bros De Lane Lea recording studio in London’s Soho, where Forster and his creative partner and co-CEO Renée Wolfe (together they work under the 2Dux2 banner) are overseeing the finishing touches to the dubbing of A Man Called Otto, a feature film starring Tom Hanks.

Fast forward four decades and a slew of box-office smashes and awards under his belt, the 53-year-old German-Swiss film-maker and screenwriter followed his childhood dream and then some. He favours no particular genre, having directed movies ranging from children’s feature films such as The Adventures of Thomas and Disney’s Christopher Robin; to the zombie movie World War Z starring Brad Pitt; to dramas Monster’s Ball and The Kite Runner; and the 22nd Bond movie Quantum of Solace (he turned down the opportunity to direct the Casino Royale follow-up). Forster and Wolfe are currently working on a Walt Disney Studios adaption of Neil Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book, which is about a boy raised by ghosts after his family is murdered; as well as White Bird: A Wonder Story, a war drama set in Nazi-occupied France in the Second World War.

What links all these films together? “They are all human stories,” he says.

He and Wolfe answer a few questions about their journeys in film.

Can you tell me about your most recent film A Man Called Otto?

Forster: It comes from a Swedish book called A Man Called Ove, which I think is even more relevant in its topics of loneliness and suicide today than when it was written in 2012. It is a powerful, life-affirming story of a man who goes through difficulties when his wife passes away, but, ultimately, he finds friendship and community. Otto is an archetypal character to whom we can all relate; everyone knows an Otto.

Wolfe: It’s meant to be an invitation to dialogue about loneliness and taboo. The minute he reaches out to the hand that’s being offered to him, he starts to transform from within. This story is about the healing of a man. We’re living in a time when there is a reassessment of what the male role is in the world. What we need is to tell stories and have dialogues about this question of masculinity and where the male resides in our lives. Christopher Robin and A Man Called Otto were consciously stories about healing a man with love and without judgement, holding him in a safe space to transform him. You can’t demand change, you can’t bully change, and you can’t frighten people to change, but what you can so is hold people in a space of love and invite that change in.

Do you feel a duty as film-makers to create films that serve a social purpose?

Forster: Our mandate is to tell stories that can elevate consciousness of the dialogue about planet or community, because we do have a responsibility as film-makers. Sometimes, as a film-maker, you come across people who recognise you and they suddenly open up to tell you stories or experiences they had as a result of one of your films, and you see that you made a difference; often it is about their personal healing.

How is the role of cinema changing and is there still a place for it against streaming?

Forster: Digital is a bit more like fast food and consumerism, whereas there is craftmanship to film-makers that is appreciated on a big screen, and sometimes fast food can be great. Just like there is a place for reading stories on a device, and reading a print magazine.

Wolfe: Cinema is changing, though, and I feel there will only be five or a maximum of 10 years of movies as we know them. In future, there will be additional experiences that are part of the universe of the main film that continue the dialogue of storytelling. Let’s say one character or scene really resonates with people, there may be an offshoot of that in a virtual space; think of the first lobby fight scene in The Matrix, it would be cool to experience that in VR. Virtual reality games, virtual cities, the metaverse, these will all overlap between cinema in future.

Speaking of the advent of new technologies, how do you think this will affect humanity in future?

Forster: Technology has developed so fast, whereas humanity and our consciousness has not developed so fast, there is a gap as we find it harder to know what is real and what is not, and that will affect our neuro-synopsis. Going back to the themes explored in A Man Called Otto, mental illness will be one of the big challenges in the 21st century and we are seeing record suicide rates. We are seeing people getting more and more medicated, it will be a real issue for people to truly feel that they have a purpose, and if you don’t have a purpose, it will be very hard to find future happiness.

Could these be the seeds of a future film?

Forster: Yes. We’ve not yet done science fiction film yet so that’s the next thing after The Graveyard Book. It’s a story about the human heart, really where technology and humanity come together; it’s about what is worth keeping in humanity as we inevitably make this launch forward into the future. It’s a story that is incredibly dear to us and one of our most important stories.

What would be your advice for budding film-makers?

Forster: Naiveté helps. When I was 15, I knew I wanted to go to film school and be a director. If anyone had told me what the chances were for succeeding, I would have probably given up. All the odds are against you in film. When I look at the class I graduated from at New York University’s film school, only a fraction is working today. But I wasn’t thinking about failure, I never doubted myself for a second. There was a moment my family said ‘why don’t you come back and be an investment banker or something’, and I said, ‘no, this is what I am doing, I am a film maker’. From a parent’s view it’s understandable as they don’t want you to suffer. Call it unquestionable passion for what you want to do.

Wolfe: We never thought we would do anything different. Even when we were sharing a studio apartment in Los Angeles: we called it ‘the shoebox’. I was doing odd jobs, I worked across the street in a DVD store. It was never: ‘This is rough, what else can we do?’ It was like: ‘This is rough, how do we keep problem solving?’ The key to succeed at anything is to keep evolving and moving towards what you want to create.

Forster: I also made a decision when I was younger to never do anything for material reasons, do what your heart wants and makes you happy. I grew up in a wealthy household but one day my father lost everything. I was surprised that I didn’t feel depressed, but then I realised suddenly my parents had more time, so gave me more attention, love, we became a family unit. There was a peacefulness in me. Because ultimately what you can’t buy is time. You only have a finite amount. If you use your time to do a job you don’t love, out of fear, you will never find fulfilment. Only if you follow your vision, passion and dream will you feel fulfilled. Yes, you will fail, and we’ve had some flops, but these are just lessons to learn from and you will come back.