At Home In Space

SAGA Space Architects is building habitats where extra-terrestrial humans could not just survive, but thrive.

The next decade will be a defining one for space travel. In 2025, all going to plan, humans will once again land on the Moon as part of NASA’s Artemis 3 mission. The first crewed mission to Mars is scheduled for 2033; engineers are even looking at how to produce bricks from Martian soil.

Space habitation is no longer a matter of science fiction, but a reality that must be considered by the planet’s designers, says Sebastian Aristotelis, the young co-founder of Danish multi-planetary architectural and technology design agency SAGA Space Architects.

SAGA is working on making space liveable for future space travellers by approaching the design of habitats from a human perspective, where space architecture is not only comfortable, but prioritises mental well-being.

“What most people don’t realise is that space is boring,” says Aristotelis. “Astronauts often suffer from depression. Without stimuli, the circadian rhythm and cabin fever, monotony and lethargy start to set in and morale can quickly drop,” he adds.

“To prepare ourselves for the day when extra-terrestrial settlement becomes a reality, we design analogue habitats, architectural experiments, habitat concepts, space visualisations, and high-tech earth architecture, with human mental well-being in mind,” says Aristotelis.

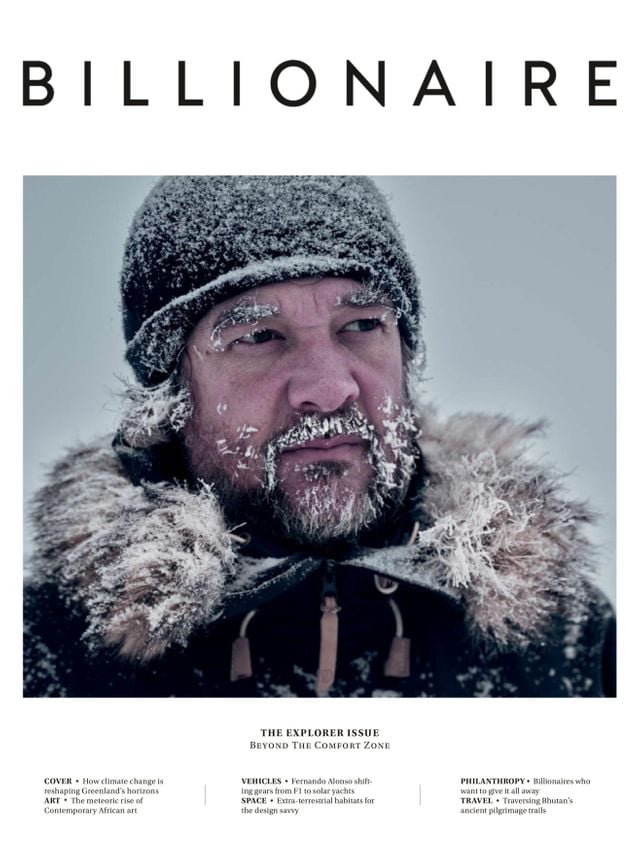

He conducted an experiment in 2020 with his former colleague, Karl-Johan Sørensen, to live in a space habitat they built called Lunark, for 60 days in Greenland, 1,000km north of the polar circle.

“It is the place on Earth that most resembles what life would be like on the Moon. With the cold we would stay inside most of the time. It was off-grid and completely isolated without Internet; it would have been almost impossible to get evacuated if something had gone wrong. Also, the landscape and the dimness made it very monotonous.”

The carbon-fibre, ovoid structure was origami-inspired, folding up to 750 percent of its folded state, making it easy to transport yet strong. “On the Moon, there is a risk of being hit by a meteor. In Greenland, you might get ‘hit’ by a 650kg polar bear.” While the habitat was comfortable enough, enduring hurricanes, polar bears and temperatures of -41°C (with wind chill), Aristotelis and Sørensen knew the real challenge would be mental.

“We gave the interiors a sense of Nordic ‘Hygge’, incorporated an algae-based life-support system to help with that human longing for nature, and created differences in temperature.”

The real bio-mimicry success was the dynamic circadian light system. “We created a synthetic sky inside that was the main contributor to our well-being. It gave us an intuitive feel of time passing when the sunlight outside was alien and monotone. Waking up to a sunrise inside our sleeping pods was an incredible natural feeling.”

They even created a variation between the days, so some days would be rich and saturated with sunrise and others would be dull and grey. Likewise, some days the daylight would be overcast and low intensity, while others would simulate a clear sky with high intensity and warm light.

When they returned from the mission, they underwent the same cognitive and psychological performance tests that astronauts do. Whereas the cognitive performance of astronauts, on a similar time frame, gets progressively worse, theirs was stable. Aristotelis puts it down to the human-centric design of their pod.

“Lunark is concrete evidence that a two-person crew in a small habitat can carry out an extended mission in Moon-like conditions. Based on the positive results from the expedition in Greenland, we’re looking into other environmental, seasonal, and weather effects to simulate. Ideally, we could emulate the sensations of rain, snow, or other weather-events inside the habitat.”

NASA has recently confirmed it will acquire the lights from SAGA to install as an experiment on the International Space Station (ISS); they will travel with the Danish astronaut Andreas Mogensen and he will trial them for six months. In the wake of the Greenland experiment, SAGA has been contacted from all corners of the world. Another prototype has been built in the grounds of Institut auf dem Rosenberg, one of the most prestigious and pioneering Swiss boarding schools. The school is known for its enrichment programme that focuses on the benefits of technology from an early age. In the grounds of the 133-year-old school, there is a Future Park where students can learn from Boston Dynamics’ dog-like robot, Spot, explore the Climate Gardens and do experiments on the school’s fleet of Audi e-trons powered by Rosenberg’s very own vertical farm and wind trees.

Now, thanks to SAGA, there is a new addition to the campus, a Space Habitat that the students co-designed with the architects. The 15-square-metre habitat is the tallest 3D-printed structure in the world. It was specifically designed to fit inside the SpaceX’s Starship rocket created to carry the first inhabitants of the Moon colony to the lunar surface, and beyond.

The students were involved in the design of the three-floor structure from the outset. Floor One is dedicated to hygiene, lab research and workshop facilities; Floor Two is designed for recreation and entertainment; while Floor Three is intended for privacy and rest. With mental wellbeing and sustainability at the forefront, just as with the Greenland structure, the floors and furniture of the habitat are multi- functional, allowing for as many various activities as possible within the limited space. With two sleeping pods on the top floor, the shape gives the primary living quarters a higher ceiling, which helps make the space feel larger.

The pod will be used by students for experiments that will include questions of human well-being, plus co-creating monitoring tools for remote mission-control systems. Learners will also explore the importance of sensory stimulation in remote living environments with light, sound and smelling simulations.

“Why would a school embark on doing a project like this?” says Bernhard Gademann, the fourth-generation headmaster at Rosenberg. “We want to educate a future generation of leaders that can go on to do amazing things. I believe what many leaders lack today is idealism, the willingness not to accept the status quo. All the problems we have today are man-made and they can all be solved by man; its why you need young, inspired minds.” More recently, a Chinese privately owned science organisation called Go Mars purchased a licence from SAGA to self-build a habitat in the desert in China. “They want it for education and STEM outreach, they were super enthusiastic. We came up with this licence agreement and they agreed immediately,” says Aristotelis.

China announced recently that it is planning for its first uncrewed Mars exploration programme between now and 2033, followed by a crewed phase between 2040-2060. It already has one of the most extensive analogue Mars simulator habitats in the world, built to house up to 28 people, 3,000km into the arid Qaidam Basin, which replicate some of the conditions on Mars.

Aristotelis predicts extra-terrestrial settlements will rapidly become a reality within the next decade. “Space habitation and extra-terrestrial living is vital for human development. If we stop exploring, we stagnate.”

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Explore Issue, Autumn 2022. To subscribe contact