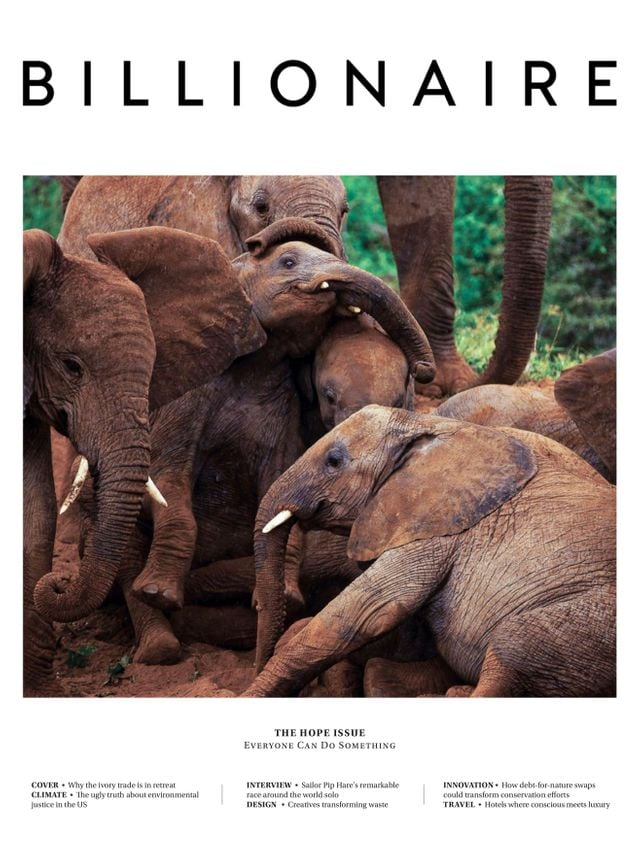

Swapping Debt For Nature

Debt forgiveness in exchange for domestic environmental conservation paves the way for others.

It is a matter of celebration that the Seychelles, a beautiful archipelago of 115 islands and one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots, should become the first country to successfully undertake a debt-for-nature swap.

A debt-restructuring mechanism was signed between The Nature Conservancy’s NatureVest and the government of the Seychelles, which pledged to make 30 percent of its Exclusive Economic Zone (essentially ocean territory) protected areas within five years. Seychelles already hit this number, in fact, a year ago, so it is ahead of schedule.

That comprises 410,000 square kilometres, an area the size of Germany, making Seychelles one of the countries in the world with the most resources given over to conservation relative to land mass and population.

It marks the first time a debt conversion was combined with major conservation policy.

For Blue Safari, an eco-tourism company established in 2018 in the Seychelles, there are only benefits to the archipelago being more protected. Blue Safari is the brainchild of South African fly fisherman Keith Rose-Innes. “My main objective was always to have a sustainable business,” he says over a zoom call from South Africa.

Rose-Innes has grown his business into a boutique holiday company offering sustainable fly-fishing tours: sustainable because they always throw the fish back alive, once caught. “After a quick photo, we return the fish to the sea and it swims away. The government now sees we can make more money catching and releasing a fish, than killing it.”

Rose-Innes runs eco resorts on four of the Seychelles islands: Alphonse, Cosmoledo, Astove and Amirantes, which are all in Zone 2, where tourism is allowed. (As opposed to the islands of Aldabra Marine National Park; Aldabra Marine National Park; D’Arros; Poivre; and the ocean area around Marie-Louise. These are all in the high-biodiversity-protected areas of Zone 1, which is strictly regulated.)

“Planning permission and development is strictly controlled in the Seychelles. You cannot build your hotel closer than 25m from the shoreline, in comparison to places such as the Maldives where many of the hotels are built on stilts directly in the sea,” says Rose-Innes. Blue Safari’s resorts have also incorporated solar power, and with 2,200 solar panels it is now 90 percent off grid. Some of the luxury accommodation is made out of repurposed shipping containers, and there is a vegetable garden that grows 80 percent of the resort’s fruit and vegetables, including watermelon, pumpkins, beetroot, limes, eggplants, beans and cucumber. Fish that end up on the guests’ plates are caught with rod and reel in deeper waters.

“Because there is so little impact, you can always see 30 or 40 turtles swimming in front of your villa. It’s as wild as you will see,” says Rose-Innes.

The outer islands where Blue Safari operates are now part of The Outer Island Project: a GEF-UNDP funded project that has been running alongside the Nature Conservancy Seychelles Marine Spatial Plan in order to ensure conservation projects and essential infrastructure and monitoring protocols are in place to ensure the successful implementation of the protected areas scheme.

Some highlights from this project on Alphonse include coral-reef and sea-grass monitoring; mooring buoys installed (to prevent anchors being dropped and destroying coral); and terrestrial areas in the outer islands receiving official government protection being demarcated.

Lifelines to places such as the Seychelles are crucial, but the reality is that if climate change is not addressed on a global scale, the Seychelles cannot be saved. Like almost everywhere else in the world, the Seychelles has been touched by climate change. In 1998 it lost up to 90 percent of its coral reefs during the biggest El Niño weather event ever recorded in the western Indian Ocean. The partially recovered reefs suffered further bleaching events from warmer waters in 2016 and again in 2019. Experts predict that unless climate change is curbed, there will be annual bleaching events around the Seychelles by 2050.

That is why the two fold debt-restructuring package for the Seychelles was crucial. Working with NatureVest (the investment branch of The Nature Conservancy) Seychelles was able to buy back US$21.6 million of its sovereign national debt from its Paris Club creditors (all EU states) at a discount; the money to buy back the debt was raised by private philanthropic funding and loan capital.

This money went into the Seychelles Climate Change Adaptation Trust (SeyCCAT), which will repay the US$15 million in loan capital over the next 10 years, as well as giving US$5.6 million to conservation and climate-change-related projects within the Seychelles and create a national US$7 million endowment fund that will ensure these conservation projects continue into the future.

The Seychelles deal could pave the way for similar debt forgiveness mechanisms in other developing biodiverse nations, says Rob Weary, who pioneered the use of blue bonds at the Nature Conservancy.

“Many SIDS [Small Island Developing States] have a number of issues that they are dealing with, many have very high debt loads that are unsustainable, some are attributable to natural-disaster recovery costs.”

A lot of SIDS are highly vulnerable to external shocks, and the combination of low growth means the countries have limited ability to invest in the environment and to adapt to climate change, points out Weary. He points to the example of Hurricane Ivan blowing through Granada in the Caribbean in 2004. Damage was 200 percent of GDP, and the island is still recovering from this after restructuring its debt with the IMF.

He is now working on a debt-for-nature swap in Ecuador, to swap public foreign debt in exchange for the government expanding ocean protection around the Galapagos Islands.

The initiative to finance ocean conservation via debt conversions is promoted by Ocean Finance Company (OFC) and Weary’s Aqua Blue Investments company. They propose to collect US$600m in funding to buy up to US$1bn in Ecuador’s commercial bonds that are currently trading with a discount of 40 cents on the dollar.

In return, the government must expand the Galapagos marine reserve, from the current 133,000 square kilometers to a marine area of up to 518,000 square kilometers.

The transaction will allow Ecuador a debt relief of US$120m through debt cancellation, US$103m in interest savings, plus US$412m via redirecting debt into investments in the country. Weary believes another 30 countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America could benefit from debt forgiveness packages in future, and the “secret sauce” as he puts it, is that the debt is given an AA- rating as it is insured by the United States’ Development Finance Corporation. He adds that some of the world’s biggest banks are interested providing the loan capital necessary to finance the deal and repacking the loan into Blue Bonds and offering these to private clients, family offices and investors as part of their CSR drive.

“It could be an absolute game-changer,” he says. “It’s a great model using financial engineering at the scale of a hedge fund, with the client being Mother Nature.”

For a blue future, unquestionably our approach has to be green.