Keeping Fossil Fuels Underground

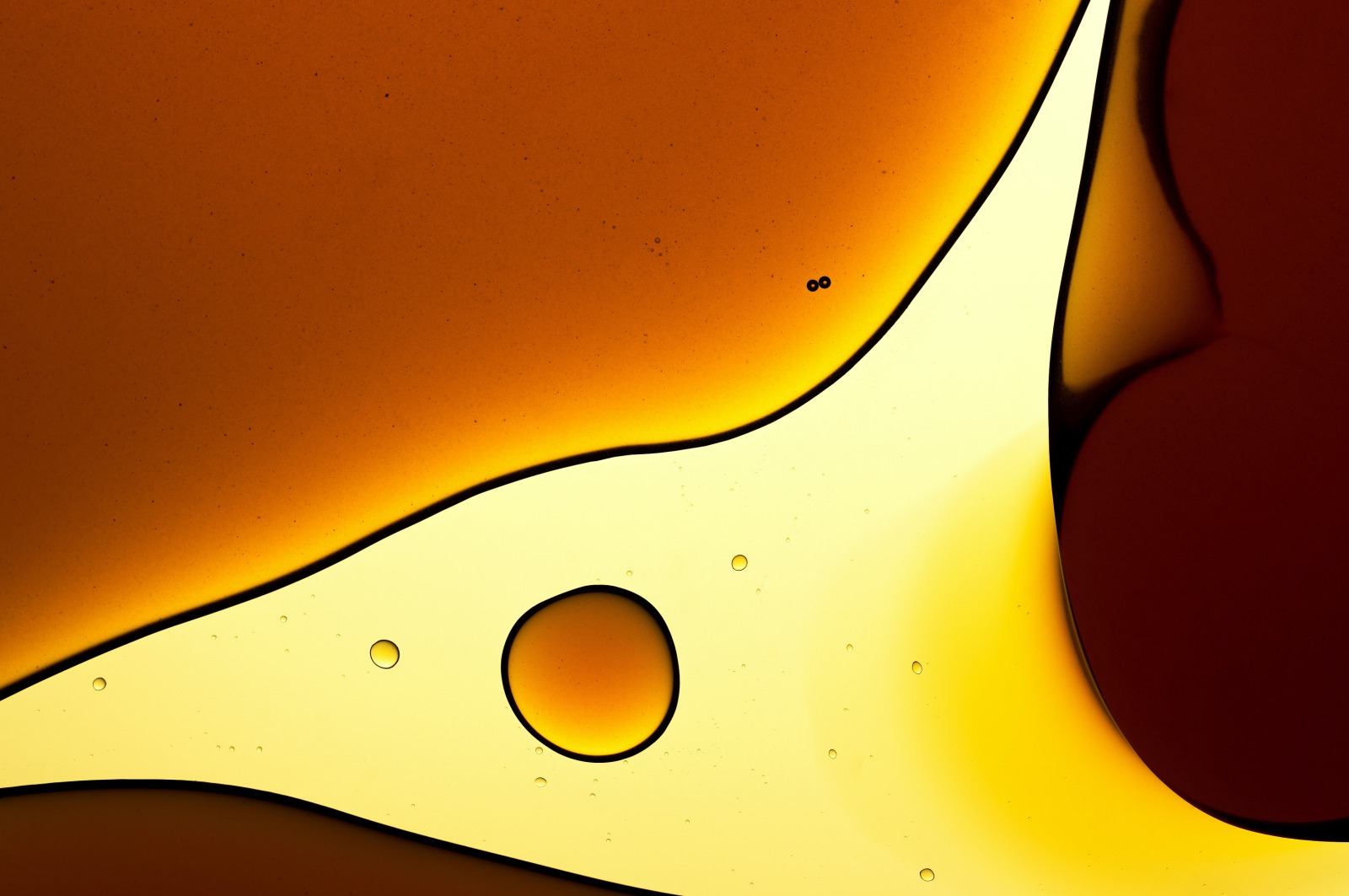

An innovation that turns waste cooking oils into airline fuel will be the biggest contributor to aviation’s net zero commitment.

On a cold, sunny November morning, a pristine Embraer Legacy 650 executive jet awaits us at Biggin Hill Airport, London, the runway glistening with last night’s frost. But, for once, this flight will not induce feelings of ‘flygskam’, otherwise known as flight shame. Our flight to Rotterdam, Netherlands, organised by private jet charter company Victor, will be booked using 100 percent sustainable airline fuel (SAF), made from a mix of discarded cooking oils and waste animal fats collected from restaurants and abattoirs.

SAF is the turning point the aviation industry has been waiting for, according to the International Air Transport Association (IATA). A so-called hard-to-abate sector over which experts have long scratched their heads; how to make flying less carbon intensive has been a foremost question ever since the 2015 Paris Agreement.

To limit global warming to 1.5C, the airline industry has to do its part by becoming net zero by 2050; the IATA estimates that by 2050, SAF’s contribution to achieving net zero will make up for 65 percent of emissions (the other 35 percent will be covered by new technologies, offsetting and carbon capture, and advances in infrastructure and operations). SAF currently reduces greenhouse gas emissions by around 80 percent over its lifecycle, compared to fossil jet fuel.

“In future, sustainable aviation fuel will do the heavy lifting when it comes to aviation achieving net zero,” says Toby Edwards, co-CEO of Victor, a UK-based private jet charter company. “Fossil fuels must stay underground. That’s exactly what SAF does. It’s reusing waste raw materials that would otherwise be discarded.”

It’s not really a question of people stopping flying altogether, says Edwards, although he adds many businesses, mindful of their reputation, have slashed corporate flights in favour of Zoom meetings. Others are buying SAF for their flights, including companies such as Sunweb Group, Scan Global Logistics, Reed & Mackay and Boston Consulting Group.

Nevertheless, global air travel has this year reached nearly three-quarters (74 percent) of pre-pandemic levels according to data from the IATA, a level from which it will be hard to meet environmental goals.

“If there is one thing that the post-Covid rebound has shown us, it is that people will always want to fly,” says Edwards. He points to the fact that in many countries, such as the UK, US and Germany, employment is at or near a record high, despite the recession. “Flying isn’t going to drop off, so we’re just going to have to do it better.”

All eyes are on SAF producers, such as Neste, an oil refinery based in Finland. Twenty-five years ago, its scientists began working on making biofuels from waste oils. Today, it is the number-one producer of SAF, and has begun using it to fly people around the world.

Our destination today is Rotterdam to visit Neste’s Netherlands-based biorefinery, where production of renewable products such as biodiesel and SAF began in earnest in 2011. Neste’s current 1.4-million-ton capacity for renewable products is the largest in Europe. We wander around the enormous plant, a vast Escher-like labyrinth of pipes and pumps. It is evidently in expansion mode, thanks to a €1.9-billion investment. By 2026, the Rotterdam plant is set to be making 2.7 million tons annually of both bio diesel (used in light, medium and heavy-duty vehicles such as vans, trucks and lorries) and SAF (used in aircraft). Victor estimates that approximately 1.52-million business aviation flights can be fuelled by the 2.2 million tons of SAF that Neste will be making by 2026.

The need has never been more pressing. Days before our visit, Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport was stormed by climate activists organised by Greenpeace and Extinction Rebellion in the build-up to the COP27 climate talks in Egypt. Their demands were simple: “Fewer flights, more trains and a ban on unnecessary short-haul flights and private jets.” Responding to the protest, Schiphol said it aims to become an emissions-free airport by 2030.

Although, of course, it isn’t as straightforward as that. The complication arises from the fact that there are currently only three Neste refineries producing SAF in the world: in Rotterdam, Singapore and Porvoo, Finland, although others are in the pipeline. To distribute SAF to all global airports where there is demand would substantially increase the carbon footprint of the practice.

Victor last year joined forces with Neste to engage in a model they call the ‘pay here, use there’ blueprint. This means the customer pays a premium to replace their fossil fuel for a booking with SAF (our flight from London to Rotterdam cost €3,520.67 to pay for 100 percent SAF, on top of the cost of the private jet, which was €25,250, so a 14 percent premium on a regular flight). Neste then supplies that exact volume of SAF to one of their partner airlines, at airports such as Amsterdam Schiphol or Helsinki. The airline will ‘burn’ the SAF and the purchased carbon emission reduction is therefore realised.

In future, as SAF production scales, refineries will become more commonplace and the infrastructure will improve, meaning that more and more flights will be located nearer to the bio-refineries themselves. This will allow transportation to make more sense and not impact the SAF’s carbon emission reduction.

The UK, for example, announced that the government is exploring a SAF mandate and is supporting the UK SAF industry with £180 million funding over the next three years to build three new SAF plants; it is also aiming to accelerate the commercialisation of SAF plants and the establishment of a fuel-testing clearing house in the UK. “We look forward to working with ministers through the Jet Zero Council to continue to explore mechanisms to attract the required private investment, in addition to a planned mandate, so we can help deliver the government’s 10 percent SAF uptake goal by 2030,” said Tim Alderslade, chief executive of Airlines UK, in a statement.

Of the 2,500 private jet flights that Victor arranges annually, around one in five customers choose to fly using SAF, says Edwards. Some of those have signed up because they have a commitment to science-based targets to try to track and reduce their emissions, a platform that 4,151 global corporates are assigned to. More demand will create more supply, says Jonathan Wood, vice-president of renewable aviation at Neste. “Hopefully at the end of the day it can be a value-added proposition, a differentiator in the market place,” he adds.

“It requires bravery,” says Edwards. “When a big corporate signs up to reduce their carbon footprint and then gets slammed for whatever reason there are then accusations of greenwashing.” That is still one of the big barriers, another being the additional costs.

What other options are there currently? Flyers can voluntarily carbon offset their flight, a way to compensate for emissions by funding an equivalent carbon dioxide saving elsewhere. So far, this has had little traction. Typical take-up for voluntary offsetting schemes lies somewhere between only one and three percent of all airline customers, according to the IATA. But, again, part of the problem is fears over greenwashing, with NGOs such as Greenpeace labelling the practice as “a scammers dream scheme”. There are also other options that will contribute to the net zero goal, such as hydrogen and electric aircraft. However, they seem unlikely to achieve certification before 2025 for short-haul flights and perhaps not until 2030 for long-haul flights, according to the IATA.

Safety is the most important part of the conversation, so every option has to be tested rigorously over many years before certification. Aircraft are only currently allowed to fly with 50 percent SAF at the moment blended with fossil jet fuel. Work is ongoing to increase this to allow 100 percent SAF to be used, however, this will take time. Neste is working with partners such as Airbus and Rolls-Royce on research into utilising 100 percent SAF and test flights are now being frequently conducted. Despite these current limitations, the Victor-Neste ‘pay here, use there’ model allows customers to purchase 100 percent SAF to fully replace their fossil jet fuel.

It may take several years before you will board a flight that is actually 100 percent fuelled by last month’s McDonald’s chip fat. But that time will come.

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Healing Issue, Winter 2022-23. To subscribe contact