Lustre For Life

As Lalique celebrates 134 years, a new cachet of contemporary crystal-making comes to the fore.

Surrounded by forests and farmland, the small, sleepy village of Wingen-Sur-Moder in north-east France may seem an unlikely home for a sought-after crystal maker. But it is here that René Lalique, considered the Jean Paul Gaultier of glassmakers, turned a glamorous vision into the foundations of an international luxury brand. A century later, it is being chaperoned into an era of five-star hotels, blue-chip contemporary art, fine dining and interior design.

“We have never seen anything like the current order book,” says Frederick Fischer, managing director of Lalique, as we tour the factory in Wingen. “Our customers were at home during the pandemic and wanted to renovate; now we’ve got a four-month backlog.” We are in the workplace of 240 for Lalique’s overall 700-strong workforce, all deeply focused: some carrying molten red-hot bubbles on sticks out of the 1,400-degree gas-fired furnace, which they slowly rotate to cool; others are delicately painting 24-carat gold leaf onto the outlines of swallows on vases that will soon be on a Harrod’s shelf with a £11,500 price tag (or at one of Lalique’s hundreds of other points of sale). These days, the traditional techniques are complemented by modern technology such as digital design and 3D printing, but the process can still take up to 40 steps. The smallest, simplest piece takes 20 days to finish, some of the more complex take months. Many of the artisans here have been here for decades; a handful are classed as Meilleurs Ouvriers de France (best craftsmen of France.)

“To make one piece, we inevitably break eight or 10,” says one of the artisans in the so-called ‘lost-wax’ workshop, where the pinnacle of crystal expression is brought to life through Lalique Art. Since 2011, this workshop has been making intricate masterpieces in collaboration with artists such as Nick Fiddian-Green, Terry Rodgers, Anish Kapoor and Damien Hirst, and architectural studios such as Zaha Hadid Design and Mario Botta, using a painstaking process of multiple moulds and casts made from plaster, elastomer and wax. To enter this workshop — where taking photos is strictly forbidden — is to enter an Aladdin’s Cave of wonders. This workshop was where The Severed Head of Medusa by Damien Hirst was created. After many failed attempts at the complicated piece, the final, perfect model was shown at Hirst’s Venice exhibition, Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable, where it reportedly sold for millions.

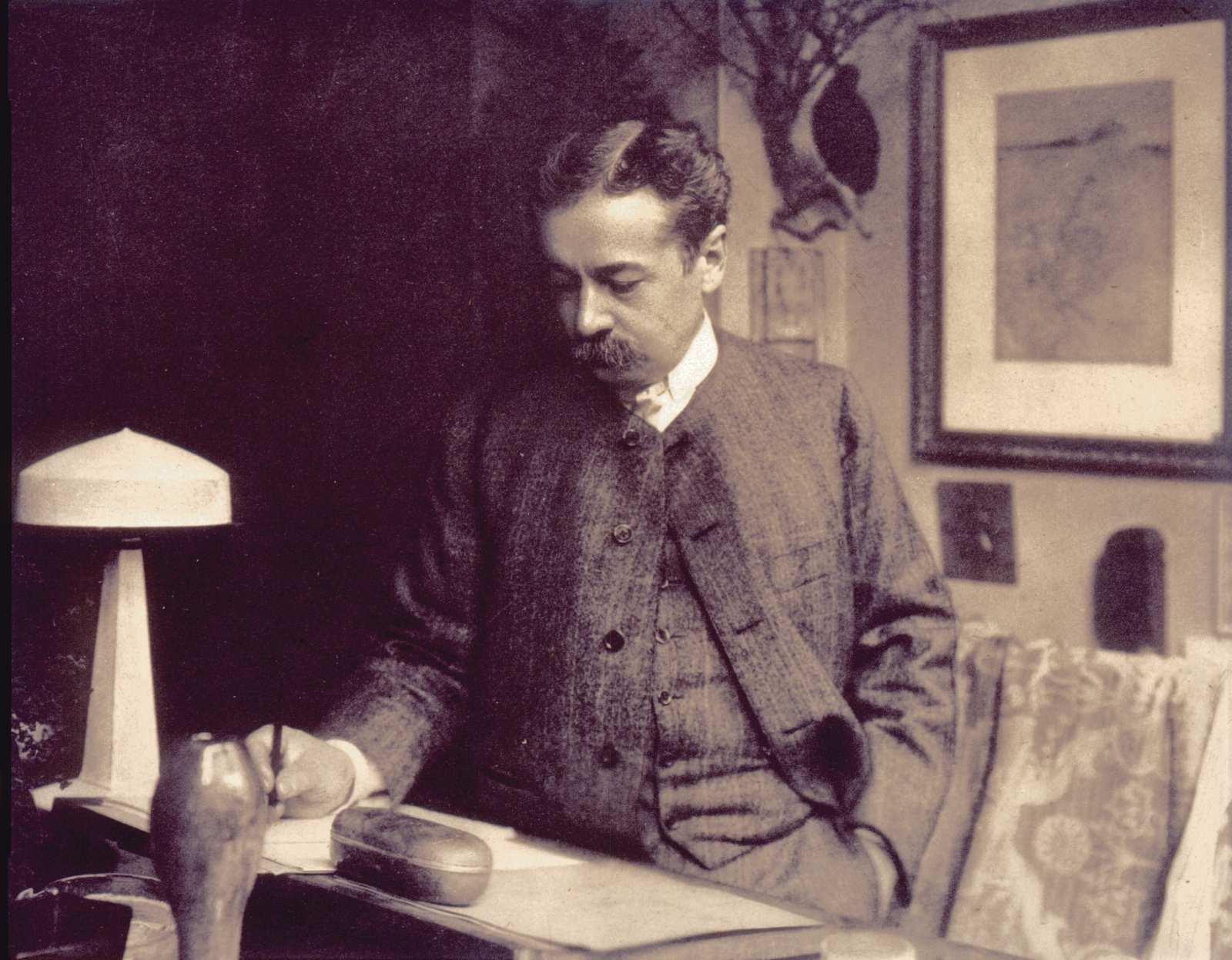

Beloved by some of the wealthiest and most influential collectors over the last century, you will find Lalique objects at Number 10 Downing Street and Buckingham Palace; Bill Clinton and Elton John are also known as loyal collectors. The late fashion designer Karl Lagerfeld would insist his soft drink was served in a Lalique Langeais glass. The brand’s cachet stems from its eponymous, meticulous, and reportedly womanising, founder, who, a century ago, was disrupting the jewellery scene as we know it.

Lalique studied in London, attending Sydenham School of Art in Crystal Palace for two years (1878-80). The Arts and Crafts movement had a huge influence on the young designer. He started his career working for Boucheron and Cartier, but then departed from their styles, eschewing their favoured use of precious stones for enamel, glass, bone and semi-precious stones such as tourmaline and bloodstone. In the process, Lalique became recognised as the father of modern jewellery.

Lalique was ahead of his time, using ‘influencers’ to promote his products. He gifted Sarah Bernhardt, the ‘divine’ French actress, all her dramatic stage jewellery. He moved on to making perfume bottles, initially for his neighbour François Coty, a famous perfumer and his neighbour on the Place Vendôme in Paris, where Lalique had a shop.

Shortly after the First World War, he decided to expand his operations with a factory in the glassmaking region of Alsace. Lalique set himself a challenge to make beauty more accessible. Glass tableware was a predominant element in the production, but his creative vision was in demand in hospitality. Lalique designed the interior of the Cote d’Azur Pullman Express train and Prince Yasuhiko’s Asaka’s residence in Tokyo. In 1928, he designed glass panels to adorn the Orient Express. Lalique panels are displayed at the Fumoir Bar at Claridge’s. René Lalique designed the iconic Poisson Fountain at The Savoy courtyard and Lalique adorns the walls of the Rivoli Bar at The Ritz.

German occupation during the Second World War shut down the factory in Alsace. It reopened after the war, but René Lalique died before he saw it. His son Marc took over, renovated the production facilities and replaced glass with crystal (with the addition of lead), taking the product into luxury realms; his daughter Marie-Claude took over in 1977, but with no heirs to pass it to, she sold it in 1994.

The latest chapter of Lalique began on Valentine’s Day in 2008 when it was acquired by entrepreneur Silvio Denz, ranked one of the 100 most influential figures of the Swiss economy by Bilanz magazine.

Since then, with the help of creative director Marc Larminaux, Denz has transformed Lalique from a 134-year-old sleepy heritage brand to a global lifestyle and hospitality brand, diversifying into the realms of art, interior design and hospitality. Now, there are “many different touch points for new customers to interact with Lalique”, Denz says over an emailed interview. Combining material goods with experiences is a popular marketing strategy pursued by luxury industry giants; Lalique is no exception. Over the past five years the Lalique hospitality stable has grown to comprise three hotel-restaurants in France, Château Lafaurie-Peyraguey in Bordeaux; Villa René Lalique and Château Hochberg in Alsace; and one restaurant in Scotland, which recently opened, within The Glenturret Distillery, with five Michelin stars between them. Denz has also been instrumental in new partnerships with other luxury brands such as Ares Design, Singapore Airlines and The Macallan.

Denz adds: “We will never stay still… by increasingly sharing [Lalique’s] beauty and magic in some of the world’s finest restaurants, including our own establishments in Alsace, Sauternes and Scotland and through the eyes of some of the finest artists and architects today such as Damien Hirst and Zaha Hadid and through partnerships with other luxury brands.

“It allows us to share… Lalique with new and existing consumers and allows us to bring all our pillars under one roof,” he says.

It starts to make sense when we sit for dinner that evening at the two-Michelin-star restaurant at Villa René Lalique: now a five-star hotel but once the family home of Rene Lalique just five minutes from the factory. The 12-course tasting menu is served on plates and bowls carefully crafted by the very artisans we met earlier; the Champagne, from Denz’s 12,000-bottle cellar downstairs (designed by starchitect Mario Botta), is poured into slender Lalique flutes, the chandelier above us glinting with multi-faceted Lalique light. When we retire for the evening to the six plush suites in the former home, it is a challenge to find anything that is non-Lalique, from the perfumes and toiletries to the bed linens and armchairs. Even the crystal sound system was a collaboration between Lalique and electronic music composer Jean-Michel Jarre.

After a full immersion, it is hard not to fall in love with a brand where pure craftsmanship remains so finely moulded into its work.

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Luminaries Issue, Summer 2022. To subscribe contact