Seedbanks: The Planet's Panic Rooms

The Anthropocene age is here and we are at risk of losing two-thirds of the Earth's biodiversity — but, thankfully, there’s an insurance policy.

The last few years of Toughie the Tree Frog’s life were a lonely time. The rare amphibian was the sole-remaining member of the Rabbs’ fringe-limbed tree frog species, discovered in Central America only in 2005. The species had been plagued with disease, which threatens as many as a third of amphibian species worldwide. Although Toughie did mate with a female, none of their tadpoles survived and she died in 2012.

When Toughie passed away two years ago in his FrogPod at The Atlanta Botanical Garden, his species was declared extinct.

But, perhaps not forever.

After his death, Toughie’s body was cryogenically frozen at The Frozen Zoo at San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research, which stores genetic material from more than 1,000 extinct and endangered animals such as the northern white rhino, of which only three now exist. The hope is that, in time, these species can be artificially recreated, for example, through insemination, in vitro fertilisation and embryo transfer, by developing Rabbs’ fringe-limbed tree frog embryos and implanting them in females of a similar or related species.

The Frozen Zoo is one of a number of institutions that are creating so-called doomsday vaults: storage facilities to preserve plant and animal species against extinction in the event of nuclear war, disease, habitat loss, devastating natural disasters, and all of the effects of climate change.

It’s the sort of pragmatism that the world needs. Whatever the reasons for climate change, one thing is certain: the world is getting warmer and it is affecting crops, plants, animals and coral life. Carbon-dioxide levels have soared since the Industrial Revolution and so has the Earth’s surface temperature, edging up by 2˚F, mainly in the last few decades. It’s a significant amount of warming that places biodiversity in jeopardy.

We look at four of the most innovative and notable ‘doomsday vaults’, safeguarding crop seeds, wild plant seeds, and coral and animal DNA.

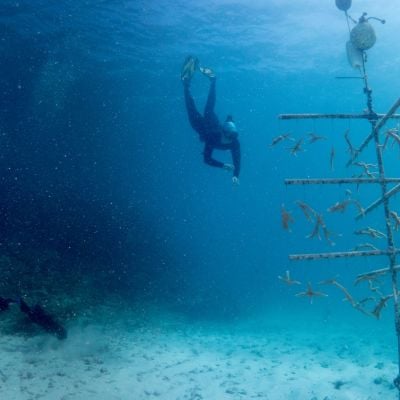

Mote Marine Laboratory

“We are witnessing the potential extinction of coral reefs,” says Dr Michael Crosby, president and CEO of Mote Marine Laboratory, an independent research institution that preserves and restores coral. “And as a scientific community, we have a choice. We can either whine about climate change and document the progressive extinction of species after species, or, we can invent technologies to actually restore ecosystems around the world, with genetic strains we know are resistant to increasing temperature.”

The 63-year-old Florida-based not-for-profit, which partners with The Nature Conservancy, grows multiple samples of three-dozen coral species indigenous to the Florida Keys and Caribbean regions in a nursery. Using an innovative technology, scientists replant fragments of young coral back onto dead and damaged reefs where they grow into healthy organisms again. “Many corals live for hundreds of years, when you see them die in the blink of an eye, you despair,” says Crosby. “But our research programme has led to a paradigm shift in the understanding of coral restoration science, and we’ve implemented a programme that I call the ‘Lazarus effect’. This involves ‘reskinning’ a 100-year-old dead coral head, and bringing it back to life in two years. It’s not science fiction, we can do that.”

Its importance has never been so catastrophically underlined. In the last two years Australia’s Great Barrier Reef has lost as much as a third of its coral due to bleaching caused by warmer waters. On a global scale, well over 50 percent of coral has died, says Crosby; in some areas, more like 80 percent. “If you wonder why that matters, you should ask yourself, ‘do you like to breathe?’”

Plants in the ocean, says Crosby, provides up to 80 percent of our oxygen. “Coral reefs are the rainforest of the sea.” And when coral dies, the whole ecosystem around it breaks down. The smaller fish that use it for shelter disappear; the larger fish that eat the smaller fish disappear; the birds that eat the larger fish disappear; and the plants that thrive on bird droppings don’t grow. It may sound like a dystopian vision but it’s already reality.

But, he cautions, his reskinning method is not a ‘Band-Aid’ to fix the larger problem of coral mortality. Without a decrease in greenhouse gases and sustainable fishing practices, coral reefs will still collapse.

“Coral doesn’t have time to evolve naturally to respond to what the environment is dishing out to it now. We’re helping the coral keep up with the insults that are coming at it, but they’re coming faster and faster.”

Millennium Seed Bank Partnership

One of the oldest world seed banks is the Millennium Seed Bank Partnership (MSBP) — set up to safeguard wild plant seeds from across the globe — coordinated by the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew. Originally founded in the 1970s by Dr Peter Thompson, it was created before concerns over climate change became mainstream. “Early on it wasn’t so much global warming, as land conversion, i.e. natural vegetation being cut down to make way for development and crops. This is still a growing problem,” says John Dickie, head of seed and lab-based collections at Kew.

The MSBP represents the world’s largest wild-plant seed bank, safeguarding well over a billion seeds, 38,000 species and around 15 percent of wild plants, from bamboo to wild bananas and all flora in between. Seeds are banked in hermetically sealed-glass containers with silica gel packets to keep them dry, and kept at -20˚C.

The MSBP’s goal is to reach 75,000 species by 2020. “We’re focusing on the ‘three e’s’ — endangered, endemic and economic — the plants that are most vulnerable and most useful to man,” says Dickie. In particular, the MSPB is taking plants from drylands, as “they tend to be neglected with the global focus on tropical rainforests”, and around a quarter of the world’s people live and graze animals in arid and semi-arid areas, under threat due to desertification. “Those plants are clever with drought stress so especially useful in coming years,” says Dickie. The partnership is also looking at mountain habitats as warmer vegetation zones move up the mountains and squeeze species off the top. “And with the sea-level rise we’re interested in islands with their endemic plant species.

“There is a danger that as we have the technology to do this for many species, it could encourage people to overdevelop and take natural ecosystems out of play, as they think they have got an insurance policy,” says Dickie. “That’s a dangerous argument. What is always more desirable is in-situ conservation, which maintains a functioning ecosystem.”

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault — Crop Trust

The need to safeguard crops is essential; it underpins nearly everything we eat and drink, says Marie Haga, a Norwegian politician and president of Crop Trust, an international non-profit that works to preserve crop diversity.

This is a fact globally recognised, and there are now as many as 1,750 crop seed banks around the world — in fact, almost every country has its own. While some of these are in excellent shape, others lack funding and proper management, and some have been destroyed in war, or through simple equipment failures. “It can be devastating if the freezer breaks down,” says Haga. Thankfully, the Crop Trust, partnered with the Norwegian government and the Nordic Gene Bank, has created a back-up.

Deep inside a mountain on a remote island in the Svalbard archipelago, a stone’s throw from the North Pole, is the iconic Svalbard Seed Vault. “Svalbard is the safety net for a huge global system,” says Haga. “Our mandate is very simple: to safeguard the diversity of the major crops that we eat around the world. We need each one, as one might have a trait we need in 100 years.” Containing nearly a million seed samples stored in sealed three-ply foil packages at -18˚C, Svalbard represents the world’s largest collection of crop diversity.

“Temperatures may increase maybe three to four percent in some parts of the world in the coming decades. We don’t know what that will mean for agricultural yields, we just know that it will be bad,” she says. “We will need to breed hybrids in future. Without diversity we can’t see how to best adapt to changes.”

Svalbard’s insurance policy has already been put into practice, when Syria withdrew a few thousand seeds from its deposit to replace those that had been damaged by the current conflict in the country.

Almost every country in the world is represented on its shelves. There are 32 different potato varieties from Ireland; around 25,000 types of soybeans; and as many as 200,000 varieties of rice. “We have seeds from North Korea, South Korea; the seeds from Russia and the Ukraine are on the same shelf,” she chuckles. “It’s awfully peaceful up there in seed land.

Unfortunately, we don’t see many initiatives these days where all the world’s countries contribute something together.”

Crop Trust also manages seed banks for Mexico, Peru, Kenya, the Philippines, and other countries, funded by the Norwegian government and large foundations, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Its budget is around US$34 million a year to safeguard “everything”, according to Haga. “That’s where the private sector can and must help us out.”

The Frozen Ark

The Frozen Ark at the University of Nottingham houses one of the largest collections of animal DNA, with approximately 48,000 samples belonging to 5,000 species. A joint charitable partnership between the university, the Zoological Society of London and the Natural History Museum, it stores DNA at -80˚C with the hope that, one day, cloning technologies will have matured sufficiently to resurrect extinct species.

Samples range from the scimitar-horned oryx (extinct in the wild); the Amur leopard (critically endangered); the Colombian spider monkey (critically endangered); and the Siberian tiger (endangered). Some DNA is already being used in direct conservation measures, for example, measuring and protecting genetic diversity in highly endangered species through providing germ plasm for a genetic rescue.

Critics have pointed out that doomsday vault back-up of animals could excuse climate change, becoming a defeatist solution to humanity’s destruction. But Mike Bruford, interim director of the Frozen Ark and professor of biodiversity at the School of Biosciences, Cardiff University, believes the two solutions need to work side by side. “Funds used for bio banks are very rarely the same as the funds used for in situ conservation, so it is not the case that we are ‘robbing Peter to save Paul’,” he says. “And these are complementary approaches. The fact is that species extinction is something we should be fighting on all fronts.”

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Ideas Issue, March 2018. To subscribe contact