The AI Renaissance

AI art means the once heavily enforced barrier between artists and tech innovators is set to blur in a way never previously thought possible.

What is art? Is it simply something we make? Or is it an expression of our thoughts, emotions, intuitions, and desires? Some would argue it goes even deeper than that, and true art becomes a way of sharing how we experience the world, and by that extension, our hidden inner monologue.

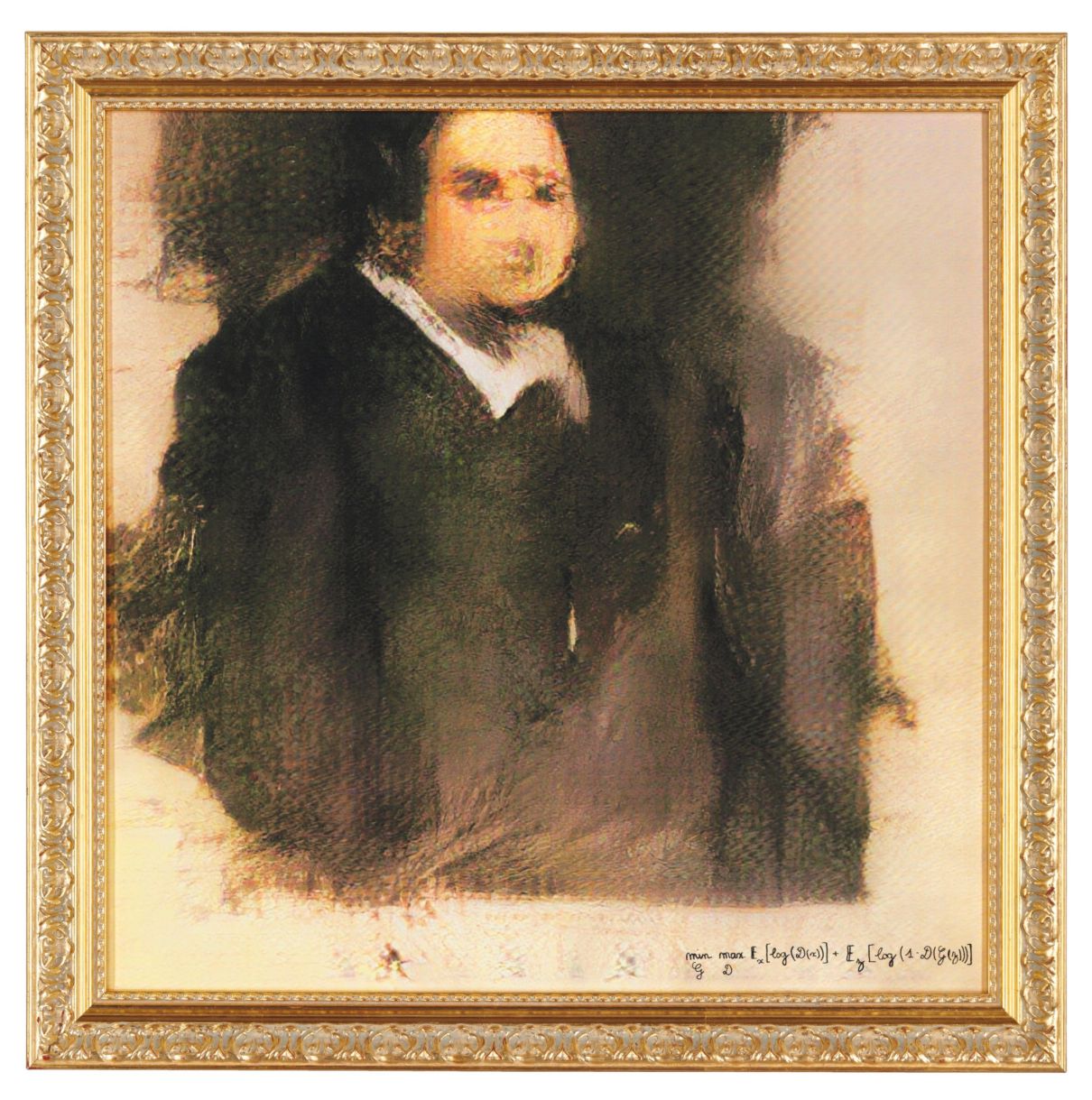

But how does our experience of art or design change when the piece in front of us has been created by an algorithm? Late last year, an ink-on-canvas portrait made by artificial intelligence was sold at Christie’s New York: the first AI-generated artwork to be offered by a major auction house. The estimate was US$7,000-$10,000. It went for US$432,500. Critics said it wasn’t art – as they once did for different modes of painting or photography – but whether you agree with the concept or not, that single sale ensured AI-generated painting, craft, and sculpture had become a new artistic medium to collect.

“There is still a fetishisation of traditional ways of making things,” says east London-based sculptor and furniture designer Gareth Neal, whose extraordinary pieces have been acclaimed globally and are partly designed by an algorithm. “But a great object or painting inspires you and makes you feel wonderful, and it doesn’t really matter who has made it, so long as it creates that feeling. The soul of an object is all in your perception of it; it’s what you imbue it with.”

Some of the biggest artists and craft makers in in the world are now using AI in their work. In New York, HG Contemporary – one of Chelsea’s glossiest galleries – recently held a month-long exhibition entitled “Faceless Portraits Transcending Time.” The catalogue describes the show as “a collaboration between an artificial intelligence named AICAN and its creator, Dr. Ahmed Elgammal,” thereby anthropomorphising the machine-learning algorithm that did most of the work. According to HG Contemporary, it was the first solo gallery exhibit in the world that has been devoted to an AI artist.

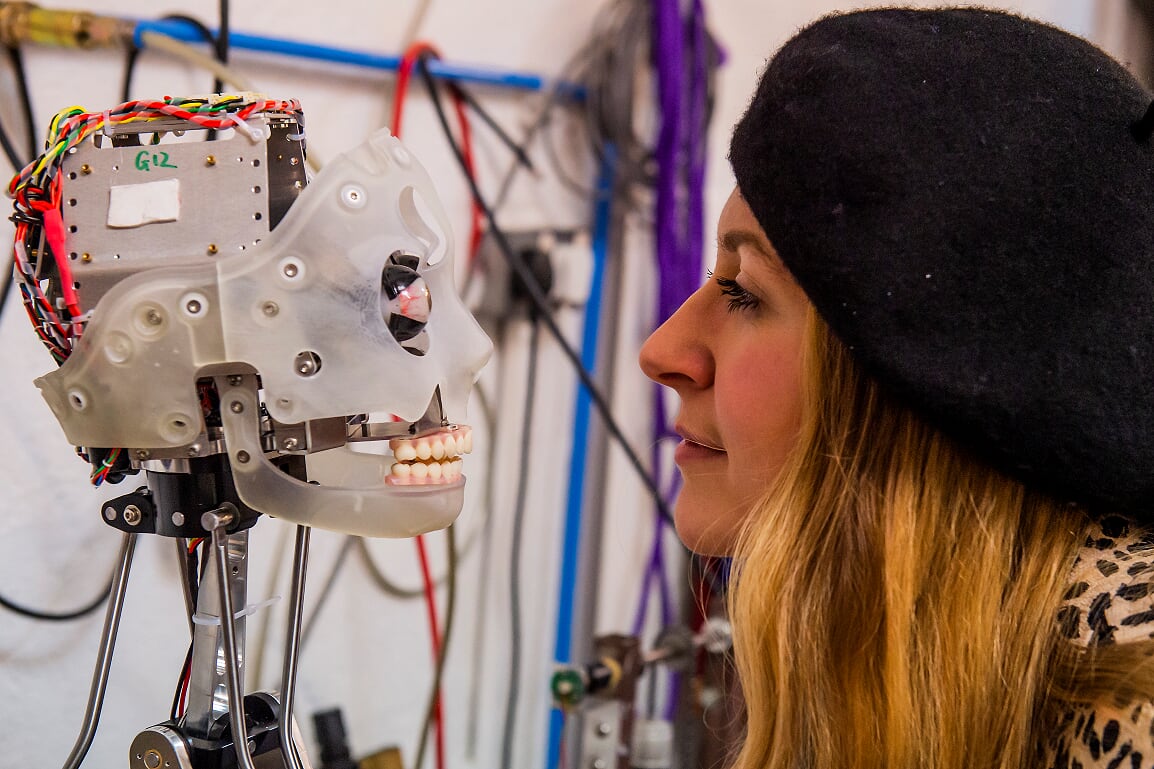

A British arts engineering company is going one step further, by creating the world's first AI robot that can draw people by using a microchip in its eye. The mechanical artist, which is named Ai-Da, can sketch subjects who pose for it by using a pencil placed in its robotic arm. Algorithms allow it to process human features, and the result is apparently ultra-realistic portraits of its subjects. Designer Aidan Meller, who is overseeing the final stages of her construction at Cornish robotics company Engineered Arts, hopes that the robot will begin talking soon and is looking forward to an exhibition of its work later in the year.

Ai-Da does, however, raise the question of what use all this development is if its end is only to build machines that do no more than mirror our own output. If we are pouring our creativity into the AI art, we must either build machines that can go beyond us – that are intelligent enough to create machines and artistic worlds of their own, without human intervention – or use their work to say something about the relationship between man and machine.

A number of artists are experimenting with the latter – one is multimedia artist Addie Wagenknecht who has programmed a robot with an algorithm to paint a canvas, but she reclines naked in its pathway to obstruct it. Or there is the installation by pioneering digital artist collective JODI, which trains a computer to play noughts and crosses. What unites them is a self-aware exploration and critical examination of the tech age and how the fusion of human creativity with new forms of innovation by machine or algorithm is creating an entirely new art form.

Hans Ulrich Obrist is the artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries in London’s Hyde Park and he has helped to make AI central to the gallery’s offering. Following digital commissions for their website, AI also recently featured in a Serpentine show by American simulation artist Ian Cheng, French multimedia art icon, Pierre Huyghe and German writer, artist and filmmaker Hito Steyerl.

And the Serpentine is not the only institution to give a significant platform to AI artworks. The Victoria & Albert Museum in London had an Artificially Intelligent display last year, and MoMA in New York held a Research & Development salon called AI – Artificial Imperfection.

The worlds of craft and sculpture have also been using AI with equal success. Neal has been using digital fabrication in his work since he was at university, which he graduated from back in 1996, and subsequently used the technique in a globally acclaimed one-off design partnership with Zaha Hadid just before her death.

“It always feels like a collaborative effort between me and the machine,” he says. “It wakes up and swings its head and gets into action, as if to say, ‘Oh thanks for using me’. I do think there is still an element of distrust from the consumer about machine-made goods that are also considered art, but that will change. And it doesn’t stop me being very grateful for the machine; it takes out a lot of the hard work and enables me to make objects that would otherwise take months. And it often takes me in a new direction I wasn’t expecting”

Ultimately, artists and designers have been relying on human advancements for centuries. Where would the Impressionists have been without the invention of portable paint tubes that enabled them to paint outdoors? Who would have heard of Andy Warhol without silkscreen printing? Seen in that sense, tech is simply another format for them to express themselves with.

“I fully support the idea of robots in craft and question why someone has to sweat and graft and hurt themselves over an object for it to become part of the prize,” says Neal. “In the past, photography wasn’t art, but we now accept that it requires serious talent to choose the right angle and know how to print and process in a certain way. It’s the same with AI. If an algorithm was created, the art was the algorithm and the artist was the programmer; the picture that came from it was an output from that art.”

And while this is a technique that seems skewed towards millennials, it is not an innovation that is used exclusively by the young. John Makepeace is one of Britain’s top furniture designers and his technique relies heavily on 3D printing and machine help. He is also turning 80 this year.

“When you’re a designer and maker looking to do the best you can, you’re open to any possible method for achieving a result,” he says. “We’re dependent on tools and machines in all other works of life, so why not art and craft? In this industry, we still ascribe to the notion of romantic handwork, but I think it is a false basis, as we’re not giving up handwork, we’re just extending our ability in an entirely new way.”

As a result, the once heavily enforced barrier between artists and tech and science innovators is set to blur in a way that we never previously thought possible. Stephanie Sy is a 30-year-old AI specialist based in Manila, who has built machine learning models and data strategies for major clients in the private sector. But in her spare time she creates AI art.

“I think of the algorithm as another sort of paintbrush, she says. “It’s a medium of expression and I can see why some people worry about the entire field of art because the medium is changing for certain people, but they shouldn’t. It’s super exciting. Don’t forget how much we can learn from machines. In the future our ideas and concept of creativity will be shaped by AI learning, and that will lead to a renaissance in how people perceive art and express themselves.”

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Art Issue, June 2019. To subscribe contact