What It Takes To Sail Round The World, Solo

More men have walked on the Moon, than women have sailed round the world solo. Pip Hare wants to change that.

Pip Hare is not the sort of person to take no for an answer. “My mother would call it sheer bloody-mindedness,” she laughs, over the phone from her home in Poole, Dorset. She is recuperating after 95 days of solo sailing during the legendary Vendée Globe round-the-world race, where she never got much more than 30 minutes of sleep at a time.

Hare jokes that she missed, above all, her coffee machine and her bed (sleep was a nap on a bean bag). But 47-year-old Hare’s feat was not for the faint-hearted. Her body and mind have been under unimaginable pressure over the last 95 days: 95 days, 11 hours, 37 mins and 30 seconds, to be exact, and her stoicism is undimmed.

But rewind a year, and it was all Hare could do to stay positive. Hare, who has sailed professionally since she was a teenager, had been offered the opportunity to charter a 21-year-old IMOCA 60 (the 60ft monohull sailed in the Vendée Globe) at what she considered an affordable monthly rate, to fulfil her lifelong dream to sail in the Vendée Globe race. It was an ancient boat, by global racing standards, built by a Swiss skipper and his friends in a hangar in Brittany. But it was a chance, and Hare had nothing else, except for her self-confessed stubborn nature.

“I looked at the charter fee and I thought, if I work really hard, I can crowdfund that charter fee every month.” Effectively, Hare created a campaign from thin air. She set up a crowdfunding page, took out a personal loan that covered the first three months to get the boat up and running. She visited local businesses in Poole, where she is now based, to ask for sponsorship. While they were able to give a little, there was no one who could give anywhere near the kind of backing (US$1 million and up) she needed to carry out the upgrades the elderly boat desperately needed.

Meanwhile, Hare kept slogging. “I did the fundraising, the admin, the boat maintenance, the racing, the coaching. My idea was, if I could keep alive for long enough and gain a place in the Vendée Globe race, someone would look at what I was doing at some point and see the value in it and a ready-made campaign.”

The wait was painful. In 2019 Hare had passed the qualifications to gain entry into the race, along with 32 others, but still no title sponsor. And then came COVID-19, with less than a year until the start of the race on 8 November 2020, leaving from France. At that point, Hare seriously doubted she would find the money she needed to properly compete.

“The thing that I heard a lot, was, ‘I can’t sponsor you, but I can introduce you to someone who can’. And you end up just going down these rabbit holes and, meanwhile, the clock is ticking,” she recalls.

“I never doubted I would do the race. I was so well supported with crowd funding and personal donations. But I doubted I could do the race in a way I could perform.”

Then, “like a fairy tale” she says, Hare’s knight in shining armour appeared. Out of the blue, she received an email from the CEO of a Silicon Valley-based software company called Medallia, which provides services for companies such as luxury goods firms Prada and Ferragamo.

Medallia was co-founded by Borge Hald, a Norwegian entrepreneur who had always harboured a dream to sail around the world. In addition, Leslie Stretch, the no-nonsense Scottish CEO of the company, has a passion for sailing, which he enjoys recreationally in the San Francisco Bay Area. It was Stretch who reached out to Hare.

“COVID had hit and I was thinking about what our brand means and how to get it next to our customers. The truth is, I wanted to have an association with a great athlete with a great story, who was circumnavigating the globe,” says Stretch over Zoom from his office in San Francisco.

He went on the Vendée Globe website and was surprised to see that one competitor seemed to be lacking a sponsor. Stretch did a bit of research, watched a couple of Hare’s videos, and sent her a message. “I see from your website that your sails are white; there’s no title sponsor, let’s have a go!”

Hare told Medallia what she needed, which amounted to a seven-figure sum. “It was pretty reasonable,” says Stretch.

For Hare, the money was “game-changing”. She took on a part-time team so she could focus on sailing the boat, and did an extensive refit, including new sails; an upgrade of the auto-pilot; a ‘coffee-grinder’-style winch; and other changes to make the boat safer and more reliable.

The Vendée Globe itself is considered one of the toughest offshore sailing races on Earth. To sail solo 24,000 miles around the planet, with no help or no break, for three months, takes a rare type of strength. It makes it understandable why, to date, only around 100 people have ever sailed solo around the world.

Her low point, Hare recalls, came just after rounding Cape Horn, about halfway through the race, when her rudder broke. She managed to replace it obviously single-handedly (“an immense physical effort that was really hardcore”, she recalls) but then a litany of issues arose from the rudder switch, leakage, problems with steering and so on. “At the time it didn’t stress me because I just had to make it work. All those ‘what ifs’, and thoughts of failure... there is no other choice but to succeed, it is so simple. But at that point I did feel like I was not in control of the boat.”

Hare had an objective to beat the current female record for a solo round the world race, of 94 days four hours and 25 minutes set by Dame Ellen MacArthur in 2001. Ultimately, Hare finished the race about a day and a half behind her goal, as the first of four British skippers to cross the line and only the eighth woman ever to sail solo round the world. As Hare puts it, “there are more men who’ve walked on the Moon than women who’ve finished this race”.

Hare’s performance has drawn admiration from all corners of the globe, in part for her drive and efficiency on an old boat, but also for her regular video and social-media posts during the race with which she hoped help to “demystify” sailing for others. She used the Medallia LivingLens, one of Medallia’s technology products, to send and receive hundreds of thousands of videos from fans.

Now, Hare’s goal is two-fold: first, she wants to change the face of sailing, which is often considered an expensive and elite sport. “Sailing is suitable for everyone. There is a huge range of facilities and clubs where you can get out on the water,” she says. Hare also has a strong sense of duty of her role in promoting sustainability, and her chosen sport powered by wind and waves could hardly be greener.

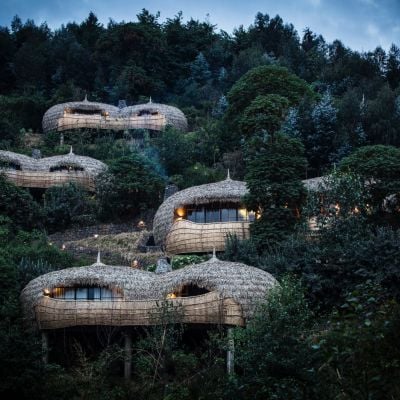

During the race she was supported by solar and hydro-power; in the next race she wants to be almost entirely zero-carbon. As we speak, the sails from Medallia are on their way to a company that will melt them into plastic pellets for use in making water bottles. The proceeds will go to an ocean charity.

Hare is looking towards 2024 when the next Vendée Globe will take place. Importantly, she will be sailing a much more modern, high-performance boat, albeit still a second-hand one, and Medallia has said it will continue its sponsorship.

It might seem unimaginable to want to go through it again, but Hare explains her reasons. “I’m just a normal person but doing this race makes me become an incredible person, by forcing me into incredible situations. It gives life a new meaning.”