Art in Orbit

In Scotland, a husband-and-wife team has built a 100-acre sculpture park aimed at inspiring the next generation.

Nicky Wilson’s happy place is being surrounded by art. This much is evident as I Zoom into her kitchen in London’s Notting Hill, where she has popped down from her main home in Edinburgh. Her backdrop is a row of monographs from ancient books by Turner-nominated Tacita Dean; she is facing a triptych of Antony Gormley paintings; the shelf above is filled with a collection of wonky Hungarian pots; a Victor Pasmore abstract is on the wall; and, in the corner, sits a gilded-and-pink lamp created by late supermodel Stella Tennant.

After our call she has a coffee date with Tracey Emin, whom she collects and has great affection for. (“She’s bloody impressive. You can’t make artwork like that unless you’re a very intelligent, perceptive human being.”) Last year, they installed Emin’s 6m bronze figure of a naked masturbating woman in a quiet woodland clearing in Jupiter Artland’s sculpture park. Emin chose the site.

Nicky’s passion for art is perhaps unsurprising as she is co-founder of Jupiter Artland, one of Scotland’s most significant arts organisations located just outside of Edinburgh. Set over 100 acres of woodlands, forests and meadows within the grounds of Bonnington House, a 17th century Jacobean manor house, a visit to Jupiter Artland’s sculpture park will take you past nearly 40 site-specific works from the art world A-list by Marc Quinn; Andy Goldsworthy; Anish Kapoor; Charles Jencks; Cornelia Parker; Antony Gormley; Tracey Emin; Phyllida Barlow, and more. Open to the public between May and September, it also includes a rolling programme of exhibitions in its four internal gallery spaces.

Wilson never set out to create an art foundation; in fact, it happened almost by accident. She trained at Chelsea College of Art and worked successfully as an artist herself for many years until her 30th birthday, when she decided that the balancing act of being a mother and an artist had become untenable. “As a sculptor my work was difficult and dangerous, with a toddler wandering around and a baby crawling across the floor.” She stopped making work thinking she would pick it up, but then kept having babies. She has five children aged between 26 and 19, none of whom, she admits, disappointingly, have followed her into the arts.

Her Irish-born husband Robert Wilson, co-founder of Jupiter Artland, is heir to the homeopathic medicine giant Nelsons (established in 1860 and best known for its Bach’s Rescue Remedy), which he runs with his brother Patrick. They had moved from Fulham to the semi-derelict 1708 Scottish castle in 1999, purely for a bit more space. Robert worked in London during the week and commuted back to Edinburgh for the weekends. Surrounded by young children and without her art as an outlet, Nicky grew restless.

“We had moved from London to this house in Scotland and I was left with the babies, in the middle of nowhere, and was fairly glum. I thought to myself: I’m not going to be like this. This place is beautiful and it needs to be shared,” she recalls.

“There was never a masterplan,” says Wilson. “It was more a conversation at the kitchen table, bouncing a baby on the knee and saying ‘let’s do this’,” she says. “The first artists we contacted to create work for us were humble enough to pick up the phone and say, ‘sure, I’ll see what I can do’.”

The late US landscape artist Charles Jencks was one of the first to arrive; Nicky hired a digger and a driver and in 2008 together they carved dramatic tiered terraces and vast lakes into the fields at the park’s entrance, like a spiritual, sculpted rice paddy. “Making replenishes the soul. My work as sort-of producer satisfied that need to create,” says Wilson.

The park blossomed from its opening in 2009 and has welcomed around a million visitors since. It runs an extensive school outreach programme. “The aim is for every school child in Scotland to at some point come and see the park for free,” she says. The programme runs on Mondays for community groups and Wednesdays and Thursdays for nurseries, schools, further education and universities. The park has won awards for the artist residencies they run on site to support postgraduate artists.

Wilson is as passionate about stoking creativity in young people as she is about art. “Creativity is not prioritised; STEM subjects is the buzzword of our time,” she says. She deplores the recent substantial drop in UCAS applications to study humanities subjects.

“The arts encourage young people to find their own voice, to discover their agency, because unlike STEM subjects, they can have an opinion,” she reasons. “It creates confidence in them and encourages elasticity of the brain to think outside the box. You can tell people who have been brought up in a creative environment. They’re the ones who believe their votes count and their input matters; they’re the future pipeline of talent. Who wants to live in a future that isn’t creative?”

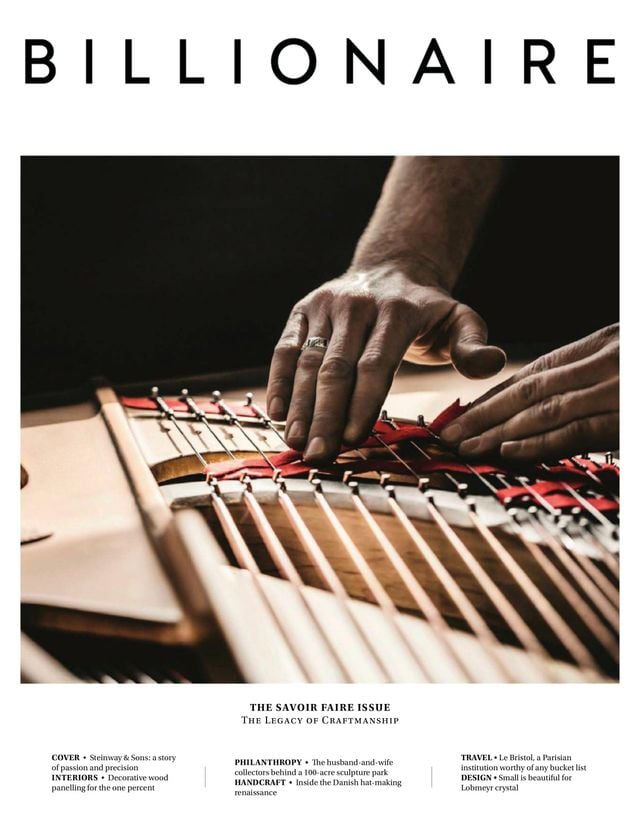

This article appeared in Billionaire's Savoir Faire issue, Spring 2023. To subscribe go to bllnr.com/subscribe