Back To Africa

An entrepreneur sees enterprise as key to lifting his war-torn homeland of Liberia out of poverty.

Chid Liberty was born in the dying days of Liberia’s old order. It was 1979, the year before 27-year-old army sergeant Samuel Doe killed the elected president and seized power in a coup that ended the reign of an Americo-Liberian elite that had ruled the country since its independence in 1847.

Liberia had been founded as a home for freed American slaves and their descendants. But in a cruel twist, the founders had ruled over the indigenous people, depriving them of land and civil rights. Samuel Doe’s revolution was fuelled by 133 years of resentment.

Liberty’s father, CE Zamba Liberty, a Stamford graduate and vice-president of the University of Liberia, was tentatively supportive of the coup’s sentiments. He had studied in the US in the civil rights era and hoped that Liberia could find a more democratic footing. He agreed to be the new regime’s ambassador to Germany and took his family there. A few years later when Doe won the presidency in a sham election, Liberty’s father made a hitlist. The family sought asylum in the US.

Today Liberty sits a world away in the small office of his clothing label Uniform in the Fashion District of New York City. A busy team of well-dressed 20-somethings work to fulfil its latest order. Racks of t-shirts and other apparel line the walls.

Liberty remembers the asylum process as a decade-long ordeal for his family. At age 15 his mother grounded him for a year. “I didn’t get the gravity of it at the time but it was my mother’s way of protecting me to make sure I didn’t get caught with the wrong crowd — being a young black male in a suburb of Milwaukee,” Liberty says. “Just so I could always be safe and eventually win citizenship.”

Liberty’s parents’ fear was that their son might be sent home to a country that had descended into chaos. From 1990 Liberia was engulfed in a brutal civil war marked by child soldiers, cannibalism and unimaginable atrocities. One in every 10 Liberians died. Half the population were forced from their homes. Anyone with an education fled. As the fighting dragged on for 14 years, many diasporans, including Liberty’s parents, gave up on their homeland.

In Milwaukee, Liberty showed an early entrepreneurial streak. He was 16 when he began managing a local college band. He booked them college gigs and built a business that he sold two years later.

Liberty spent his 20s in California’s tech world but eventually he began thinking about his homeland. The war had ended in 2003 with Charles Taylor’s exile. In 2005 Liberians elected Ellen Johnson Sirleaf to the presidency. She was Africa’s first elected woman leader. Johnson Sirleaf had a degree from Harvard and international experience with the World Bank and Citigroup. International investors and donors poured in hoping that she would bring Liberia’s long nightmare to an end.

A chance meeting at Sundance Film Festival led Liberty into the world of social enterprise. He met Abigail Disney who was making the film Pray the Devil Back to Hell, documenting the role of Liberia’s women in pushing political leaders to peace. The star of the film, Leymah Gbowee, was eventually awarded the Nobel Peace Prize along with Johnson Sirleaf in 2011.

Liberty found the movie life changing. He’d been a volunteer for Barack Obama’s campaign a few months earlier and was energised by a feeling that, “ordinary people to band together and do really amazing things”.

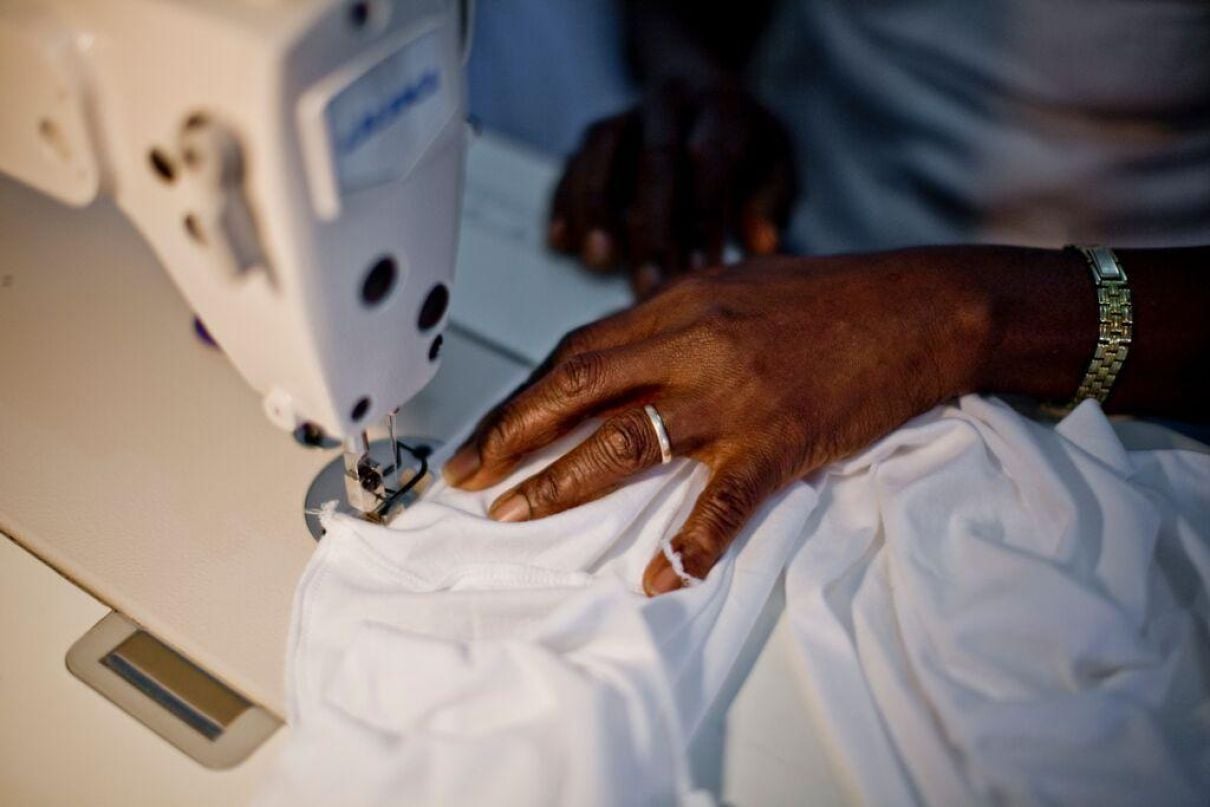

He decided to set up a business supporting Liberian women, “to turn what was a peace movement into a jobs movement”. Liberty and Justice, Africa’s first Fair Trade certified clothes factory was launched in 2010. Disney was an early backer. Prana, a sustainable clothing company, offered a contract before he’d even set up a factory.

At the same time Edun, a clothing company started by Bono and his wife Alison Hewson, had suffered big losses because of quality-control issues in Kenya and Uganda. “It didn’t help that everyone who had tried to do this had failed miserably,” Liberty concedes. Edun was bought by LVMH but many investors still had doubts. Liberia was no Kenya. The war had left it with no power, no infrastructure and no real business climate.

“By far the only thing I had on my side was naivety. That was the secret sauce. We had no idea how dumb we were being.”

Despite teething problems, by 2014 business was rocking. The company signed two agreements worth about US$40 million a year with US brand Haggar and Japanese trading company Itochu. The deals would create 2,500 jobs in Liberia and thousands more in other parts of Africa. Liberty and Justice spent US$1 million on a factory, machinery and training new workers.

Then Ebola struck. Most of their 300 workers came from the nearby slum of West Point. Liberty realised “if one person gets sick and comes to the factory, we’re gone”. Days later the president declared a state of emergency. West Point was put under military quarantine. “We pretty much knew that was it.”

Liberty and Justice provided cash and food for the workers. None of the workforce came down with the virus. But more than 10,000 Liberians were infected and 4,810 people died. It would be nine months until Liberia was declared Ebola-free. The orders went away. The company had political risk insurance but no insurance had foreseen Ebola.

The road back has been long. In the Waterside Market community of Monrovia the factory is running at reduced capacity. Forty workers still come every day — most of them have been with Liberty and Justice from the beginning. Rows of empty sewing stations are a reminder of an opportunity lost.

"It’s a totally made-in-Africa apparel brand. I’m excited as an African about all the things going on on the continent and being able to make very competitive clothing and having an industrial revolution that looks very different from its predecessors in the West and in Asia. We have the opportunity to for instance, power our factories with green energy and to embed worker rights and wealth creation in everything we do."

The business has kicked up again with a one-for-one model. Uniform sells high-end t-shirts in Bloomingdales. For every t-shirt sold, one child in Liberia gets a free school uniform. Liberty expects to announce more retailers soon. His investors have stayed on board through it all.

Liberty has no regrets. “I would rather learn the way we did than be among the people who hear ‘Liberia and anything innovative’ and just stop the conversation right there,” he says. “At some point these things are going to break through. If we just say, the government’s too corrupt, the people are uneducated, the banks lose all their money, we’re assigning Liberia to this future that will make this a certain failure. If we can muster up the courage to say we’re going to try some new models and we know that some of them are going to fail and we’re okay with that, then I think something positive can really happen.”

Liberty has a message for people who are thinking about investing in Africa but nervous about the risk. “I think people have mispriced the risk in that they are really, really, really scared of Africa,” he says. “I see that as an amazing opportunity because any time that people have mispriced risk due to discrimination somebody else has come in and made a lot of money. That’s what we hope to do. While other people continue to misprice risk we hope to be the ones coming in and making money and doing a lot of good while doing that.”

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Journey Issue, September 2017. To subscribe contact