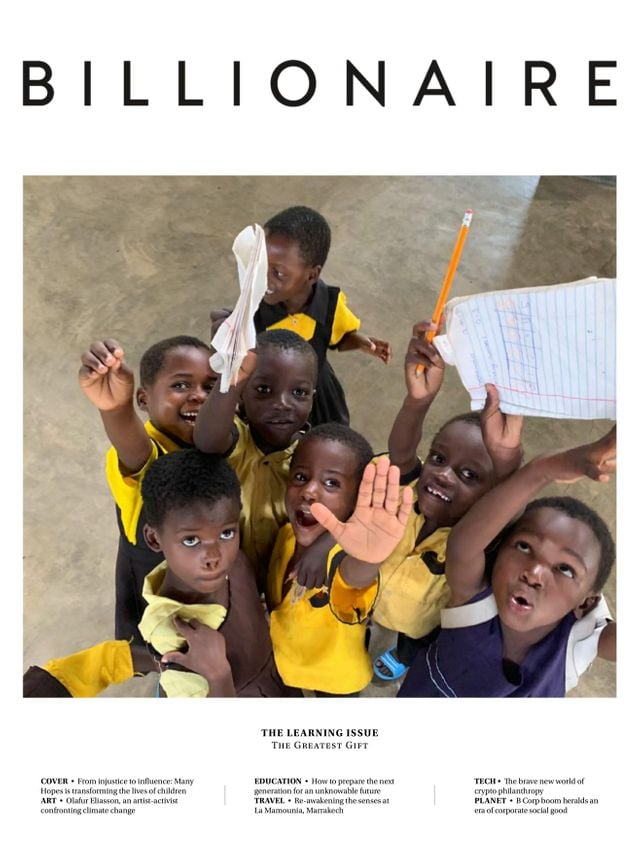

From Injustice to Influence

Many Hopes rescues children from injustice and equips them to become change-makers themselves.

“There is no one more determined to defeat injustice than the child survivors of injustice,” says Thomas Keown, Northern Irish co-founder of the children’s charity Many Hopes.

Over Zoom from his home in New York, Keown is recalling some harrowing stories of children who have escaped slavery and abuse in Africa, and gone on to be successful lawyers, bankers and then, in a virtuous cycle, rescuers for other abused children.

He points to the story of Brenda, one of the first girls rescued by Many Hopes’ Kenya partner, now a young woman in her late 20s who is now advocating for change.

Brenda never knew her father and her mother died from HIV, leaving her orphaned when she was young. She was tricked by a woman claiming to be her aunt, who took her in and put her into domestic service as a child, routinely physically abusing her for falling behind on her chores. Brenda ran away, and fortunately was discovered by the co-founder of Many Hopes, Anthony Mulongo, a field reporter in Kenya, who gave her a loving home and pushed for the prosecution of the woman who abused her, culminating in a jail sentence. Brenda was sitting in the courtroom for the trial, and turned to the Many Hopes partner and said: “I never thought that someone like me could be in court. I want to become a lawyer and defend the rights of other children.”

Thanks to the support of Many Hopes, Brenda graduated from university with a law degree and passed the bar this year, with a goal to help other children escape dire situations.

Many Hopes operates in Bolivia, Peru, Guatemala, Kenya, Malawi and Ghana. It works by developing relationships with high-profile community-minded individuals and organisations in grassroots areas, who are supported with funds from the charity to rescue children from abusive situations and provide them with a safe and loving home, education, counselling and financial support. It currently serves 3,000 children with plans to rescue 20,000 survivors and equip them to rescue others.

Finding the committed, trustworthy, on-the-ground individual or organisation, says Keown, is the hardest piece of the puzzle and also the key to effecting real change. “While you need external help at the start, we believe that real transformation, that lasts, must come from inside a person or a community,” he adds.

Keown points to James Kofi Annan, who is the Many Hopes partner working in Ghana. As a six-year-old, James was sold by his destitute mother into the commercial fishing trade on Lake Volta in Ghana, a vast man-made lake that is a hotspot of child trafficking. According to Many Hopes, some 21,000 children are enslaved on fishing boats, half of them under 10 and a quarter under the age of six.

“There is a low value of life here; a child is worth less than a fishing net, so frequently lose their eyes or their lives diving into murky water to untangle nets from trees,” says Keown. James escaped at the age of 13 by hiding himself in the boot of a car. At the time he could not even write his own name. He managed to find a job, put himself through college, got a job with Barclays Bank before deciding to return to the lake to free more children. To date, he has rescued 1500 children from slavery and wants to help thousands do the same. He brought schooling into his local community and began to transform the lives of other children. “Because of me, so many children began to go to secondary school; through me, people have gone to colleges and have diplomas,” says Kofi Annan in a video. “Now, those that have had their lives changed are changing the lives of others. Within a short time, survivors of trafficking become the solution to the problem.”

Rescuing children is not an easy thing to do, adds Keown. In order to carry out a rescue, the Many Hopes partner must hire a boat and organise policemen to attend who require payment to help. In addition, local families are not always aware that their children will be taken into slavery. Single mothers are often targeted by traffickers, claiming they will give their child a job where they will send money home to the family, and come home after a stint. For those on the breadline, it can be an offer too good to refuse.

The goal is, Keown says, in partnership with other charities, to eradicate child slavery on the lake completely, within 10 to 15 years. Part of this will come from the virtuous circle of Many Hopes alumni, he says. “We’re trying to raise a small number of young people who will go on to help the millions,” adds Keown. “Children who survived injustice will be adults of influence preventing millions of others from suffering what they did.”

There are other goals too. This year, the charity will go from an annual budget of about US$1 to US$1.5 million to about US$4 million, helped by its loyal donors, including the Hovde Foundation, which funded the construction of its first rescue homes and now sponsors overheads so as 100% of public donations go directly to the mission, and the Buckingham Foundation, which recently bestowed a US$300,000 matching fund grant. It has also a new annual giving programme called The 72, which involves a three-year commitment of US$10,000-US$50,000 per year; so far, 37 families have committed. In addition, Many Hopes partners with bank charity trading days, including the Cantor Fitzgerald Charity Trading Day in London and the ICAP Charity Trading Day in New York, where 100 percent of global revenues from that day is given to charity.

The extra funds will be put towards expanding new reach to enable support of another 2,000 children, building new schools such as the Mudzini School in Kenya that opened last year, with the capacity for 900 children in 44 classrooms.

“When we meet girls in the streets with no homes and no food and rags for clothes and we ask them ‘What do you want us to do for you?’ the answer is almost always the same: ‘Take me to school,’ says Keown.

Keown himself didn’t come from a privileged upbringing, he just saw injustice and wanted to help. Growing up a farmer’s son from Northern Ireland during The Troubles, after a degree at Queens University, Belfast, he worked on the Belfast Peace Agreement. It was during a visit to East Africa in 2007 that he saw injustice that truly appalled him, and he met Anthony Mulongo who at the time was running a girl’s home. Keown thought: “If people back home could see what I’ve just seen they would want to do something.” So, he returned home to Boston and wrote a piece for the free Metro newspaper about his experience (“it was rather sanctimonious”) but the next day his editor called to say there had been a flood of emails and calls from people wanting to help.

Keown responded to them all, arranging a meeting in a windowless conference room in his office in Boston, the very next night. Around 30 people turned up who became the founding volunteers. “Many Hopes was born that night,” he says. People started to host events at their house or work place and invite him to talk, and the word spread.

“My central thesis I was sharing at these events was: no one cares more about justice than someone has experienced injustice,” says Keown. “They had a tenacious desire, more desire than any charity worker I ever met, to stop other children going through the same thing. This is unrealised potential that we have here. If we can find a way to provide thousands of these children with education in their heads and confidence in their bellies and a network at their fingertips, the world is different in 25 years.”

This article appeared in Billionaire's Learning Issue, Winter 2021-22. To subscribe contact