Good Call

Phones4U founder John Caudwell was only a child when the idea of being wealthy enough to give it away first struck him as appealing.

It is, as psychology has charted, an unusual trait in any leader or self-made person to attribute their success to anything other than their own genius. But, refreshingly, John Caudwell says his own achievements are in some part down to genetics. “Some entrepreneurs just get a great product right and the rest is easier. But at the sharp edge of commerce, as I was... to do business like that you have to be genetically predisposed to it,” says Caudwell. “Of course, you need to work very hard on top of that. But it’s the difference between a great athlete and a world champion: to be world champion you need the genetic edge. And since I was six or seven I had a deep desire to win.”

Caudwell is the man who, in a tale that threatens to sound apocryphal these days, was in his mid-30s and working as a car dealer at auctions when he saw a man using a clunky, chunky, device the size of a suitcase. It was a mobile phone. “I recalled my childhood when anyone who had a home telephone was a messiah in the area. And within 20 years of that it was strange not to have a phone at home. And I figured mobile phones would go the same way; that it would be more imperative to have one,” says Caudwell.

So, he contacted Motorola, bought 26 phones, and took eight months to sell them. But he stuck with it. Two decades or so later he’d built his company, Phones4U, into one with a staff of 10,000, selling 26 phones every minute. In 2006, just as consolidation in the mobile phone business threatened a downturn, and predicting a national recession to come, he sold up and pocketed some £1.5 billion, a fortune he’s pushed over the £2 billion mark since.

“There was an emotional attachment to Phones4U but the daily stress and pressure of the business was at an incredible level. I really had had enough of living at the precipice,” he recalls. “I reckoned I could be in the industry for another 10 years and end up no wealthier than I was.”

And being wealthy is important to Caudwell although not for the most obvious reasons that it keeps him in fast cars, ski chalets, loud jackets and helicopters, all of which he’s partial to. Sure, he has no interest in business that doesn’t make money. His latest pursuit is property. Or, more specifically, the building or renovation of prime real estate in London’s Mayfair and along the south coast of France. He recently acquired the Provençal hotel building on Cap d’Antibes and is working on two other nearby developments, Parc du Cap and Les Oliviers, as part of what he calls the Caudwell Collection.

In part, his interest, now that phones are behind him, is in creating a legacy. These are projects that are “something special, that make me proud: taking historic buildings and protecting them; or taking ugly buildings and replacing them with something beautiful,” he says. “But there has to be profit for me to do anything in business at all.”

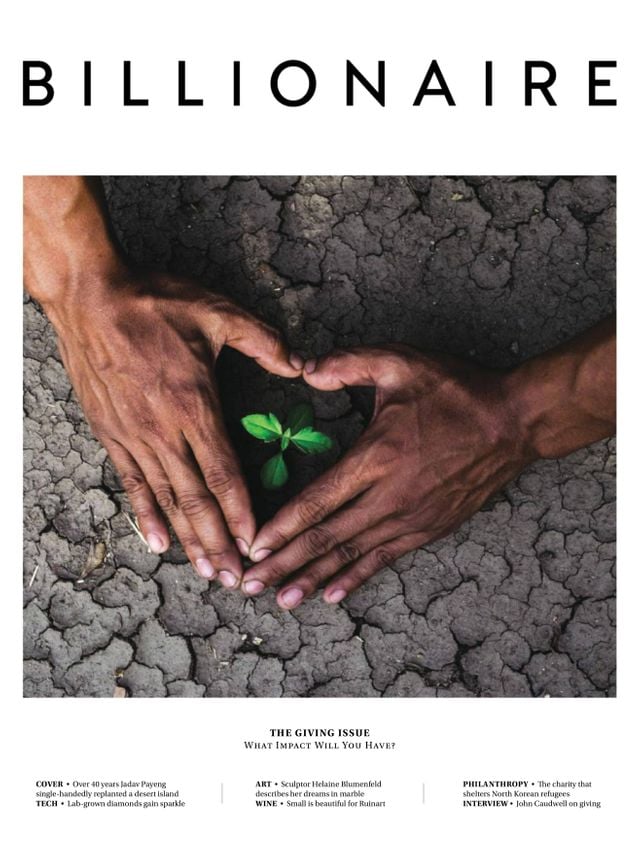

That will be because the more wealth he accumulates, the more he gets to give away. Caudwell was one of the first British billionaires to sign up to the Giving Pledge of Bill and Melinda Gates and Warren Buffett. The pledge is a commitment to give at least half of one’s wealth away to charity on one’s death. But he seems to be enthusiastically giving it away long before then. His Caudwell Children charity focuses on helping families with seriously ill children who have reached rock bottom. “Most of my family died of strokes or heart attacks so I could have focused on that, but it would have been in self-interest. Children just seem to me to be the obvious target for philanthropy,” he says.

Indeed, Caudwell says he was a child himself when the idea of being wealthy enough to give it away first struck him as appealing. “At the age of seven I had this vision of myself driving around in a Rolls-Royce handing out fivers, which is very strange for a seven-year-old,” he chuckles. “That was my idea of philanthropy then, I suppose. But philanthropy gives me immense satisfaction — a spiritual wellness. And the fact is I’ve been incredibly lucky and using that money to improve things is an imperative part of my life.”

He adds: “I feel obliged. Why, I don’t know. But I see how the world is a horrific place for a lot of people and I’m in a position where I could improve thousands, maybe in the end hundreds of thousands of lives, so I don’t see how I could justify not doing so when I have the amount of money that I do. If I had half a million I would be less sure. I’d still want to but would feel less certain about my ability. But with this amount of money, yes, there’s an obligation.”

Not that Caudwell just throws his money around. As well as being focused on a few core charitable concerns (for example, he also operates charities for largely under-served people suffering from Lyme disease) he is also intensely focused on how they’re run.

“My feelings about philanthropy have always been the same: it’s about doing the most for the most people at the lowest cost, so, for me, philanthropy has to be immensely efficient. It’s my money, but it’s other people’s money too so we have to deliver value,” he says. “We’ve got phenomenal returns on the money delivered. We negotiate hard-ball to get the best deals possible. And it really bothers me when charities waste money. And even more so when they’re nepotistic, giving money to favoured businesses, for example.”

Caudwell plays a strategic part too, by putting himself at the centre of the action. He’s an enthusiastic cyclist and regularly rides to raise money. A few years ago, he rode from one end of Britain to the other, raising some £60,000 in the process. Why did he bother, for such a relatively low sum? “Of course, I could put another £60,000 in from my pocket but what’s the point of that?” he asks. “That doesn’t really grow the charity. What does is getting people to buy into the charity with hearts and minds. It’s not just about giving money but creating advocates for what you’re doing.”

Remarkably, he’s enthusiastic (“well, I wouldn’t say enthusiastic exactly,” he laughs) about giving his money to the state too, because he sees paying his taxes — rather than dodging them in Monaco — as part of his humanitarian thinking. He concedes he’s not above managing his tax contribution, and further concedes that, were the British government to tackle the “already-too-big” divide between rich and poor by introducing a punitive tax rate he might radically re-think his position. “But if you’re planning to give most of your money away when you die anyway, isn’t it socially responsible to contribute to the government’s efforts to help people too? There’s a responsibility to contribute to the country that helped make us,” he argues.

Indeed, it’s the kind of unusual lesson (unusual among the very wealthy, at least) that’s he’s tried to instil in his four children. Perhaps they too have benefitted from the money-making-cum-philanthropic gene but, all the same, he’s set on not spoiling them with overwhelming inheritances. “The only thing that matters to me is that they’re happy, whatever happiness is for them, and that they try to leave the world a better place,” he says. “Of course, they’ll never be poor. They’ll always be privileged. And the amount of money I’ll leave them could ruin the wrong person. So, it’s been about encouraging them to be the right person, not a trust-fund baby. I’ve always told them that I’m giving all the money away to a cat’s home. And they have never batted an eyelid. But they do all have cats, so perhaps they’re hoping to be beneficiaries through that…”

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Giving Issue, December 2018. To subscribe contact