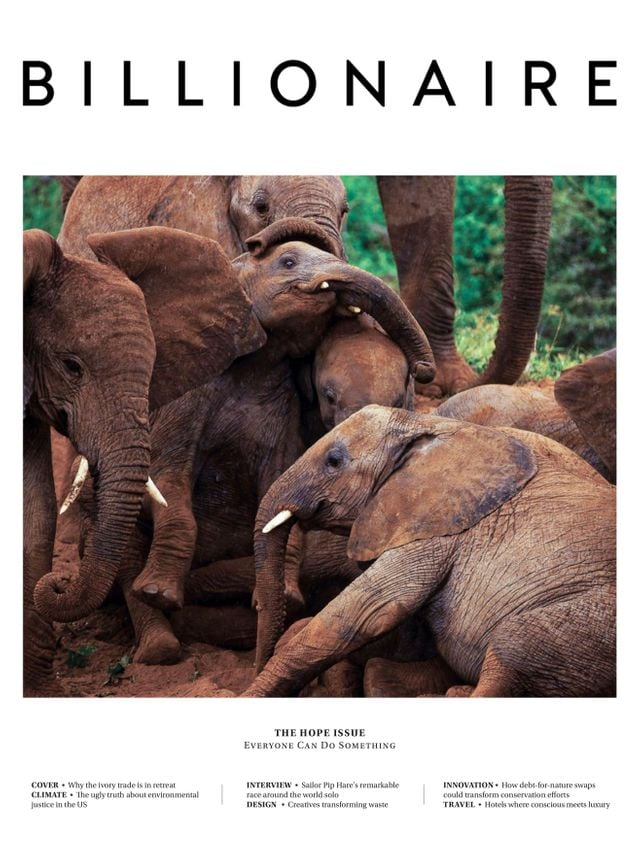

Reinvesting In Earth

The founder of the Global Returns Project on why private individuals, rather than governments, are key to solving the climate crisis.

If you had told Yan Swiderski 10 years ago that he would have become a beaver expert, he might not have believed you. “Life throws some interesting curve balls,” he agrees over Zoom from his home in Cornwall, UK.

A Cambridge law graduate with a 30-year career in international finance, specialising in sovereign debt and currency markets, Swiderski held top posts in Singapore, New York and London. In 2002 he founded an investment management business with three friends, Finisterre Capital, managing global portfolios investing in over 50 countries, primarily in developing markets.

But in 2014, after having sold his business, he swapped city suits for wellington boots in the fields of Cornwall, where he acquired a large rural estate: Hamatethy Farm. In the years to follow he and his wife Camilla (a former Greenpeace campaigner, originally hailing from Cornwall) converted the estate to organic by cutting out all chemicals and pesticides, selling off the sheep, and turning the majority of their land into a rewilding project.

This meant allowing nature to take its course, a process aimed at boosting natural biodiversity and reintroducing indigenous species that had disappeared from the area, usually due to the expansion of agriculture.

Recent additions to the neighbourhood include storks, leverets (young hares) and water voles. Of particular excitement, is the resident family of beavers, which are building a dam on the river that intersects 500-plus acres of land. This, says Yan Swiderski, is amazing as beavers have only just been reintroduced into the UK after they were hunted to extinction 400 years ago. He animatedly lists the ecological benefits they can bring to the environment by alleviating flooding and accumulating water wetlands for other biodiversity.

The career change from fund manager to organic farmer and environmentalist might seem unusual, but it made perfect sense, says Swiderski.

“I was becoming increasingly concerned with the state of the world; as a fund manager you’re evaluating the situation with all the information you have, peering through the fog to second guess the future. The climate-change situation was becoming increasingly alarming,” he recalls.

As the problems became more apparent, Swiderski started to despair. “I would have meetings with companies about the environmental effects of their activities and some of them just didn’t even understand the question.”

He started blogging about environmental news and observations and circulating it among friends. “After a while, my friend Jasper said: ‘Yan, you keep sending this terrifying stuff, what are we going to do about it?’”

Swiderski organised a brainstorming session with some friends. They established that the quickest way of effecting change would be through encouraging private wealthy individuals to give a small proportion of their assets. The world’s private individuals globally own some US$140 trillion, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers, of which they are largely free to spend how they want.

“Governments and corporations are not moving fast enough to address the planet’s problems, whereas private individuals have more autonomy over their spending and can often make decisions more rapidly than the inertia in those institutions,” he reasons.

After a few months of research, Swiderski and his colleagues came up with the Global Returns Project, a platform with a goal of raising US$10 billion every year to tackle the climate crisis. He intends to raise the first US$10 billion within the next 10 years.

It sounds an ambitious target, he agrees, but Swiderski explains his rational like this: if just three percent of the world’s private individuals gave 0.25 percent of their savings each year to not-for-profit climate change, they would be able to raise US$10 billion. The 0.25 is not legally binding, says Swiderski, but more of a “promise between you and future generations that you gave 0.25 percent of your savings and investments to projects that tackle climate change”.

Climate change is already a brutal reality for millions, with the most extreme impacts concentrated in developing countries in the global south. Global average temperatures are already around 1.1 degrees higher than pre-industrial levels. The World Bank has stated that tackling poverty and climate change are now inseparable aims. Current national commitments to greenhouse-gas emissions reduction and environmental action only deliver about one-third of the emissions reduction needed, and time is running out.

Climate philanthropy has so far been dominated by the ultra-rich with foundations, for example, Jeff Bezos, who recently announced he would donate US$10 billion to climate change, or grassroots campaigns such as Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth and Extinction Rebellion.

But the mass affluent and high-net-worth individuals (those with liquid assets of around US$1 million) have historically been less engaged with philanthropy, because of the size and scale of the task at hand.

Swiderski agrees there is not much point in doing something for climate change unless it is on a grand scale, which is why he came up with a target of US$10 billion annually. And when you quantify it, at a quarter of a percent it is hard to make a case not to give. But he wants to target everyone, for example, if someone has £4,000 in savings, they would give £10.

“The idea is to mobilise people to make it easy for them to give a tiny proportion of their wealth,” says Swiderski.

The Global Returns Project distributes 100 percent of its funds to a selected group of climate-change charities, including Trillion Trees, a joint venture between BirdLife International, Wildlife Conservation Society and WWF to tackle deforestation; Ashden, a London-based charity focused on sustainable energy; Rainforest Trust, a US non-profit that protects tropical rainforests; Global Canopy, an alliance of scientific institutions; and Client Earth, which uses the law to protect the planet.

By presenting would-be donors with a list of vetted charities, it means they don’t get the “choice overload” problem, says Swiderski; sometimes time-short people don’t donate because they don’t know whom to give to. “Everyone is busy and hopefully this will provide confidence we have done the due diligence in finding the most efficient NGOs,” he says.

The Global Returns Project has so far raised £100,000 after launching in November 2020. But Swiderski is still hopeful of meeting the mark of US$10 billion within the next 10 years. He imagines that when the first one or two ultra-high-net-worth individuals have signed up, more will follow. It is a Herculean task but nothing could be more worthwhile.

“We are not calling it investment and it’s not philanthropy, it’s reinvesting in Earth. We think everyone should do this.”