Sumatran Story

Behind the scenes of an immense Indonesian effort to save the critically endangered orangutan.

Stories often materialise when you least expect them. I first visited Bukit Lawang, Indonesia, as a tourist hoping to see orangutans and was duly rewarded for my efforts on a hot, humid, jungle trek. The moment I encountered an orangutan, I felt a connection with this species that shares a whopping 97 percent of our genetic heritage.

The experience prompted me to do my homework as a photojournalist and now, one year later, I’m back in Sumatra for this story.

It begins with a rescue in the jungle, a rubber plantation, where I quickly discover the number of people involved in saving just one orangutan. A call from a local man to the Orangutan Information Centre (OIC) in Medan, has triggered a meticulously coordinated effort, starting with the immediate dispatch of a two-man team to the site to verify the information: Is it an orangutan? What is the precise location of the sighting? Has more than one person seen the animal(s)? “We get three to four reports like this a month,” says Panut Hadisiswoyo, founder and chairman of the OIC. “Before we allocate full resources, we want to be certain.”

Within hours, I’m tagging along with North Sumatra team leader, Bedul Siregar, veterinarian, Tengku ‘Jeni’ Adawiyah and other members of the Human Orangutan Conflict Response Unit for the five-hour drive to Bangun Sari, a small village in Aceh Tamiang province, where nine of us settle in with a welcoming local family for the night. Deafening rain pummels the aluminium roof as I fall asleep.

It’s 7am as the team heads single file into the rubber plantation for what they refer to as a morning walk. Orangutans spend their days moving through the tops of trees feeding primarily on fruit, bark and vegetation. Every evening, they build a new nest. But their routine is being sabotaged. Haphazard clearing of the forest creates pockets forcing the animals into plantations as they search for food and lodging, resulting in conflict with plantation workers.

Two scouts have gone ahead. Communicating by walkie-talkie, the search lasts three hours with no result. Wilting from the effort, the group returns to the village. Just as lunch is finishing up, the call comes in and, within minutes, I’m again trying to keep up in the thick, muddy brush. And then, there it is, high up in a tree. Team members vigorously shake branches and call out, enticing the animal down to within safe range for Rudi to fire a tranquiliser.

The orangutan struggles against the effects of the dart, eventually releasing its grip and falling towards the outstretched net. Demun and Bedul brace for the catch, but the animal’s weight against the extremely steep, slick terrain sends the trio (and myself) sliding. The groggy orangutan tries to lift her arms in protest, but gently drifts into sleep as the men secure the net and carry her down to level ground where vet Jeni performs a thorough medical check. Although blind in one eye, with several air-rifle wounds on her body, the 15-year-old female is in good condition and everyone agrees she is fit to be released back into the forest. It’s a race back to the jeep to secure her in the transport cage before the sedative wears off. In the oppressive humidity, I struggle to recover from the gargantuan effort. The problem now is there is a palm-oil plantation standing between us and a viable release location in the Tenggulun protected forest. In order to shave four hours off the journey, team leader, Bedul puts in a call to the BKSDA Conservation Agency to request permission to drive through the plantation.

Night has fallen when the cage is placed flush against a tree. As the door panel is lifted, the orangutan bolts straight up and disappears into the foliage in a flash to the collective gasp of the onlookers. The weary team returns to the host family for the night, exhausted but proud of the work accomplished.

Over the next few months, I participate in several more rescues with either an immediate translocation or, if the orangutan is injured, transport to the fully equipped medical facilities at the quarantine centre of the Sumatran Orangutan Conservation Programme (SOCP).

One rescue is particularly traumatic. We drive 10 hours overnight to a site in Aceh province where reports have come in of an orangutan wandering in a palm-oil plantation. Given the flat terrain and easy access, the entire village tags along for the rescue. The orangutan is quickly located but sedating her is tricky as she is holding a baby. When the tranquiliser begins to take effect, a team member climbs the tree and gently lifts the baby away as the mother slips into sleep. The on-site medical check reveals that she is blind and riddled with bullet wounds. She must be transferred to the clinic for immediate medical attention. But, on the way, all concern turns to the baby who is suddenly in distress. Despite veterinary efforts to resuscitate him, the baby dies before our eyes. The crew is absolutely devastated, and a sombre mood lingers the entire drive back.

It is 9pm, 24 hours since the start of this ordeal, when SOCP veterinarian Yenny greets us at the quarantine centre an hour and a half outside of Medan, rushing the mother, who the team has named Hope, into the clinic. An X-ray revels no less than 74 air-rifle wounds. “I’m horrified by all these bullets, but I’m much more concerned by Hope’s broken collarbone and possible infection,” exclaims Yenny. Meanwhile, earlier in the day Brenda, a baby orangutan confiscated from locals, arrived at the centre with a broken arm. Yenny hardly thinks twice. “They both need surgery.”

“While Hope and Brenda hardly resemble most of my patients, anatomically they are similar as are the operating techniques,” says Dr Andreas Messikommer, a Swiss orthopaedic surgeon who has flown in at a moment’s notice to operate. “Being part of this process and contributing to the preservation of the species is very rewarding.” It takes six hours to complete both surgeries.

Over the next few months I return often to the quarantine centre to observe routine medical checks. Orangutans such as Hope, Leuser, Chrismon or Fahzren, who have been severely injured or domesticated, will live out their lives here or at the Haven, the SOCP’s soon-to-open protected sanctuary nearby. But the greatest reward for everyone working with orangutans is the release of those who have assimilated the skills to survive in the wild. Preparations are underway for six specimens. One by one, the animals are carried piggyback or transported by wheelbarrow to the examining room for a final medical check. As if to protest their departure, heavy rain explodes from the sky as each orangutan is placed on a bed of leaves in a cage and loaded onto a truck. Accompanied by vet Yenny, they will travel 15 hours overnight, then transfer to jeeps for the two-hour jungle-track drive to the reintroduction centre located in the Jantho Pine Forest Nature Reserve in Aceh.

Forest training will continue here as keepers evaluate whether the animals are sufficiently prepared to survive in the wild on their own. Caregivers focus on three factors: ability to build a nest; find fruits and leaves; and, finally, how willing they are to distance themselves from humans that have been caring for them. As the sun sets, the orangutans return without incident to the safety of the large forest cages. This monitoring will continue for as long as necessary. Eventually, on graduation day, the orangutan is ferried across the river and released into the protected national park.

Since the centre opened in 2011, more than 100 orangutans have been reintroduced into their natural habitat. “Every orangutan we are able to release is a major contribution to a new, genetically viable, self-sustaining wild population, and to the long-term survival prospects of this critically endangered species,” says Ian Singleton, director of SOCP.

--------

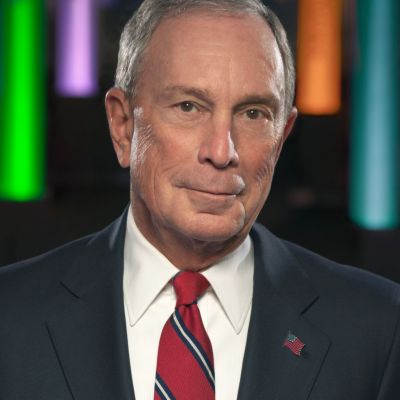

Interview: Ian Singleton, director of SOCP

Does the SOCP have a specific goal for how many orangutans you will have saved/released in the next five to 10 years?

Our goal is to have at least 250 surviving reproducing animals in each of the two new reintroduced populations. Given that not all will survive or reproduce, we would like to release at least 350 animals in each before we would consider them potentially viable and self-sustaining in the long term. In Jantho, we have released 120 over eight years, which averages at 15 per year; 350 minus 120 is 230 and 230 divided by 15 gives us 15 more years to achieve that. In Jambi, we have released about 180 so far, since 2003, which is 11 per year, and 350 minus 180 is 170, and 170 divided by 11 is also about 15 years. So that would be our goal for the two reintroduced populations, meaning we need decent long-term funding support to achieve the targets.

Do you think the efforts of the SOCP will be enough to save the orangutans from possible extinction?

Yes, in the Leuser Ecosystem we still have around 13,000 orangutans. If Indonesia can better protect its forests and prevent further fragmentation and degradation there’s still a good chance that there will be enough orangutans remaining in big enough populations to still be viable over the long term. But we are not there yet. In the Batang Toru, we are already close to the minimum viable numbers, and every individual or hectare of forest really counts. Those animals cannot tolerate further losses or fragmentation. We are creating two entirely new genetically viable and self-sustaining populations, which will act as a safety net should some catastrophe befall the existing remaining original wild populations.

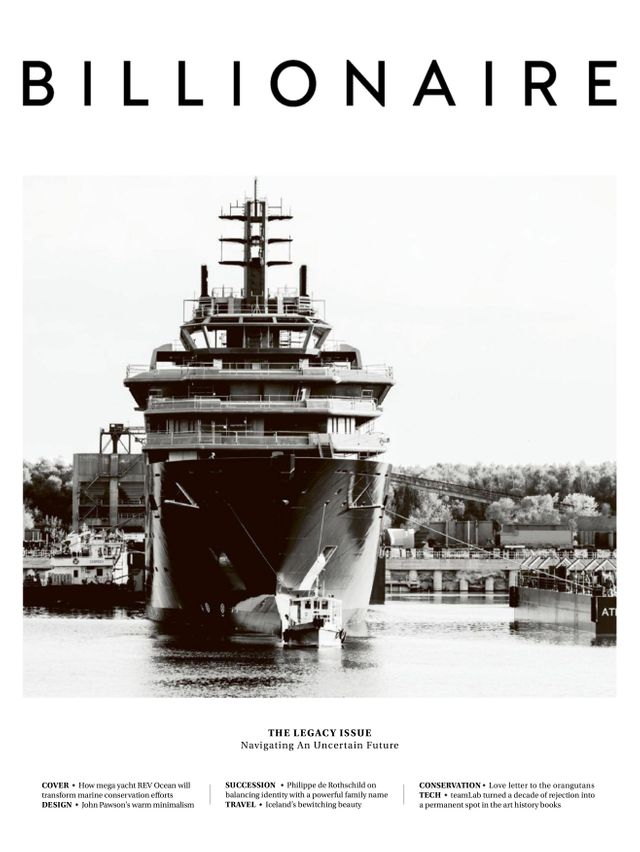

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Legacy Issue, March 2020. To subscribe contact