Wånas Konst: Where Art and Nature Coincide

Put Wanås Konst on your bucket list, a stunning non-profit sculpture park in the grounds of a medieval castle in Sweden.

A family-run medieval castle, an organic farm, and art to discover as far as the eye can see (across 40 hectares). It sounds a little like a fairytale, but Wanås Konst is a real, interactive sculpture park filled with site-specific art of artists like Yoko Ono, Antony Gormley, Per Kirkeby, Tadashi Kawamata and Ann-Sofi Sidén.

The acclaimed outdoor art programme is one that seeks to “challenge and transform our view of society”, according to founder Marika Wachtmeister in 1987. Today, the sculpture park and permanent collection consists of around 70 site-specific artworks in the landscape created especially by artists both established and new.

Alongside co-director Mattias Givell, Swedish curator Elisabeth Millqvist runs the commissioning side: with site specific art installations, a dedicated program for children, outdoor sculpture park, she turns this site in rural Sweden into a stand-alone art destination.

Millqvist sits down to discuss the vision with Billionaire.

How have things changed for women running art institutions?

Today as a woman directing a cultural foundation, you’re surrounded by other women in the same position. In Sweden today, a great majority of art institutions are run by women, that means you’re always in very good company. I feel very fortunate to have access to a powerful network that feels very natural.

There are soft power qualities in women, that are often hard to see, that means being supportive of, or creating situations for artists that work for them. There is often more compromise and open mindedness, more humanist values. I know that running an art residency, I need to be understanding, create the best conditions for artists. On the artist side, as craft is coming up more and more in visual arts, older women artist are getting into the spotlight. I don't know if that is correlated but there is a definite interest nowadays for traditional crafts created by women.

At Wanås, you look at art and makers as an ecosystem, with production workshops dedicated to different crafts, residencies, exhibitions, architectural experiments, performing arts, festivals. How do you make it all work hand in hand?

When we start planning for the year ahead, we invite artists and not their artwork: we ask them to respond to Wånas and its natural environment. We ask them to explore new boundaries, work with the local industries. That often pushes artists to explore new directions.

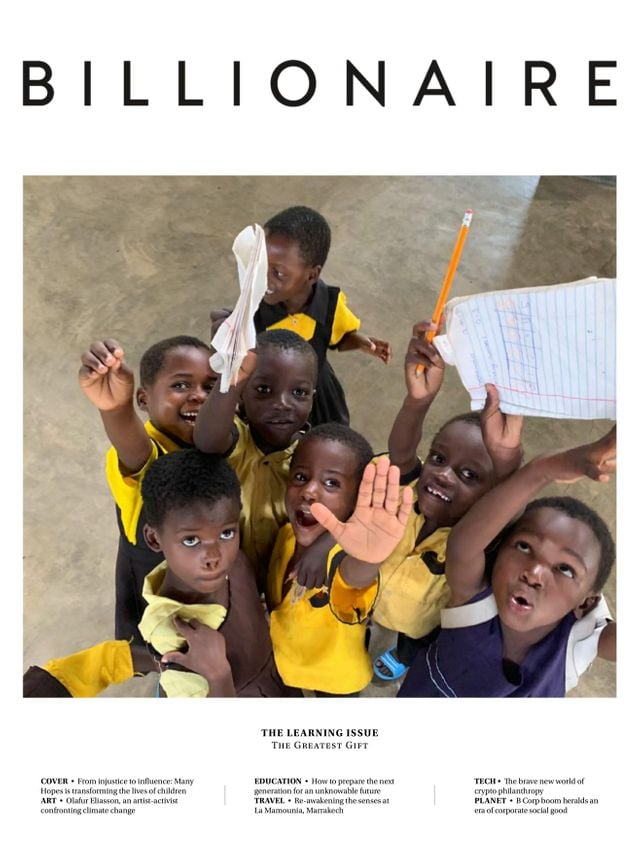

In parallel, we embrace children: we like to have a very varied audience, which we need to build. The artist can have a positive impact, but we need to be in dialogue with our future visitors. Be an inviting force. Look at how artists push forward, on track to something else: the same goes for children.

All falls into place when you consistently balance everything, with the right purpose: treat visitors, children and artists the same way. At Wånas, we favor an unhurried art experience: we take our time, we work with fewer artist, on longer projects.

It is fascinating to see how you brought together contemporary and local culture.

When artists come, they teach us about what is here. One noticed we always had bricks, so we should have had local manufactures. He wanted to learn about clay: that led to a project where ceramicists recommended other ceramicists to revive and challenge this know-how. As a result, a ‘new local clay’ was invented.

How important are children for the future of the foundation? Do you work with artistic practices tailored to them?

During the pandemic, we worked with an artist studio from the Philippines who are used to working only with children. It soon became obvious that they would not be able to come. Rather than canceling, we realized community projects are about dialogue, so they crafted a very simple film to help share their vision. Using brown carboard paper and a glue gun, each child was offered to create his own home and talk about how he felt this your home could be like. Our educators worked with local schools and online: 1500 children collaborated, and we displayed all the houses stacked up like a Babel tower at Wånas.

If you have the right contact, you can do meaningful project. I wouldn’t have trusted the process, yet it shifted our perspective on the power of collaborations. Not only were we able to carry it out but it gave us a lot of energy: it was nurturing both ways. We also learnt a lot about the perception of our homes shifted during the pandemic – homes could be about confinement as well as about being warm and safe.

The foundation develops year after year: what are the next steps?

One exciting thing is that we are creating a home – like a hub or maker’s space - for the educational work: for that, we are turning the art gallery into an educational space. We’ve been working with children since 1997, and welcome 10 000 on average every year, who attend specific programs. In addition, we want to work on longer projects to create true impact like with teenagers. All we aim for is create new opportunities for the young.