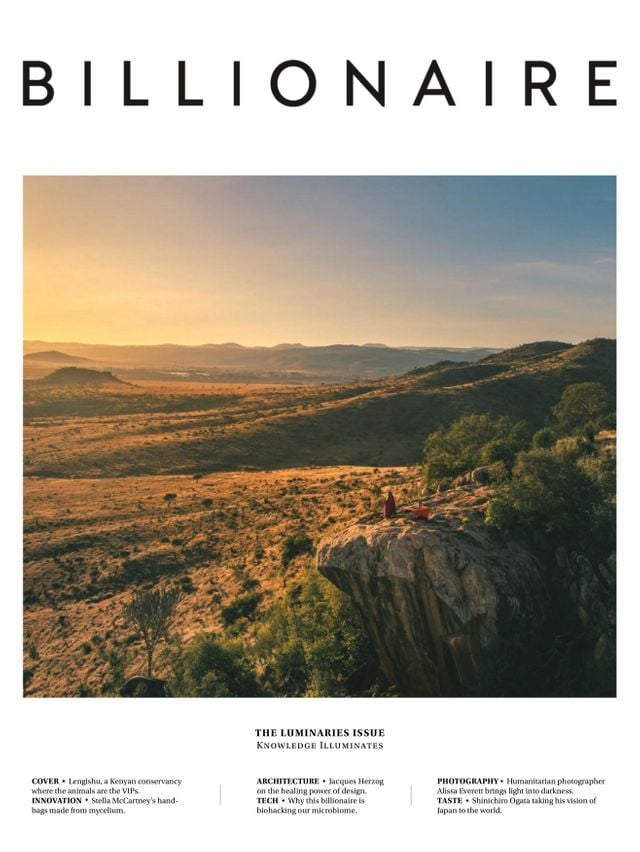

Wild At Heart

An exclusive-use lodge and a Kenyan wildlife conservancy where the animals are the VIPs.

As our little green Cessna Caravan descends towards the uninterrupted horizons of Laikipia, Kenya, the pilot warns us about warthogs on the runway. Earlier, the dirt-track strip was in use by a family of “pumbas”, he explains. “I’d have to do another loop until they’ve moved on.”

Our destination is Lengishu, an exclusive-use luxury lodge and private home, perched on the Laikipia Plateau, in the foothills of Mount Kenya. As we are about to learn, at Lengishu the animals that roam in the 32,000-acre Borana Conservancy are the VIPs.

Welcoming us off the plane are our hosts and the owners of Lengishu, Joe and Minnie MacHale, a British couple who split their time between Kenya and rural Hampshire. Minnie fell in love with the African country after spending our years living there during the 70’s: “It sowed a tap root in me which I then instilled in Joe, and our children,” she says. Then an opportunity came up to become the fourth shareholder of the Borana Conservancy, a reserve in the hands of the third-generation Dyer family, who still retain five shares. They jumped at the chance to build a family home to enjoy with their four children and growing brood of grandchildren.

Had it always been the plan to create a lodge? “Absolutely not,” says Joe emphatically, as we bump along in one of the converted Land Rover Defenders, its interior encased in buttery Dorper sheep leather, retrofitted with polished wood interiors and padded khaki canvas.

He looks at Minnie, behind the wheel, expertly navigating the stony paths. “But at what point did it turn from being our home, into a lodge?” he asks. Minnie scratches her head, she isn’t sure, either. “It sort of just grew into the idea until it made sense. Initially we planned to have eight staff; actually, we need 25 to keep it ticking over.”

It was a happy accident and, from a conservation perspective, a no-brainer. Since the MacHales first came here in 2015, Joe tells me, the rhino population has increased from 165 to 256 across Borana and the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, the partner reserve. With the exception of one unfortunate incident in 2019, the two conservancies have been poaching-free. “Winning the war against poaching is partly through the ranger patrols, but even more so by winning the hearts and minds of the locals,” he says. “When they see a something or someone that doesn’t look right, they report it.”

Winning the war against climate change is not so straightforward, though. As the road twists up towards the lodge the land is parched brown. The MacHales agree it is the driest they’ve seen in May, historically a rainy month. “Global warming is without doubt a growing problem,” says Joe.

At last, we arrive at Lengishu House, typical in gorgeous understatement; no signposts, no pomp and ceremony. Built with thatched rooves and natural stone, shaded by gnarled wild olive trees and thorny acacias, Lengishu is as well-camouflaged in its natural habitat as the tiny lizards that scurry along its paths.

Minnie and Joe take us on a tour of the exclusive-use lodge, which opened in 2018. (Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta was their first paying guest, according to their guestbook.) Pathways are edged with colourful, drought-resistant beds, fiery red succulents, scented lavender and aloes in shades of pink, orange and green, their tendrils twisted like mysterious sea creatures. Spotty guineafowl weave through the undergrowth. A weathered garden gnome peeks out from a patch of sedums. “He came with us from Hampshire,” says Minnie.

Inside the cool stone walls, an eclectic treasure trove of antiques, furniture, art and photography are displayed with taste and care against the raw Kenyan timber, including some good black-and-white wildlife shots taken by Henry, their eldest son. The aesthetics of Lengishu are the vision of Ben Jackson, a builder, and Emma Campbell, a designer, with input from Minnie. Each of the six bedrooms is different and quirky, humour and authenticity always evident. A metre-high wooden parrot guards the bed in one room. “We found him on a quayside in Turkey on a family holiday 15 years ago, we felt he belonged here,” says Minnie. An iridescent gold mural by David Marrian is the centrepiece of another (“we built the whole room around the colours in this”).

Rich terracotta bedspreads and soft furnishings are sourced from nearby artisans; wooden bird illustrations for which the rooms take their names, are painted by a friend’s daughter; and the antiques, from the silver serving trays to the wooden port box we use for al fresco sundowners, are cherry-picked from Sunbury Antiques at Kempton Park Racecourse, where Minnie (beautiful and elegant: think Julia Roberts with a pixie cut) is known on a first-name basis.

Each room enjoys a large stone fireplace or a woodburner where a fire of eucalyptus wood is lit nightly as part of the turndown service, and a freestanding copper bathtub with vistas over the plains. And when it comes to sustainability Lengishu walks the talk, run almost entirely off-grid with its 270 solar panels providing 75kw of electricity. It also has a grey-water recycling facility to irrigate its herbaceous borders and its herb and vegetable garden.

The sense of it all is of an intimate, family home, albeit a luxurious one, organically grown rather than purpose-built. “It might not be everyone’s cup of tea,” says Joe, over dinner. But it’s hard to imagine who wouldn’t feel warmed and welcomed by its relaxed charm.

Of course, it takes deep pockets to run a wildlife conservancy, and the returns, although perhaps not monetary, can be very rewarding. The seed of the Borana Conservancy was sown in the 1990s when the Dyer family, the then owners of the 32,000-acre ranch, realised that to combat the effects of drought and climate change they would need more hands, not to mention cheque books. They decided to turn Borana into a conservancy, retaining five shares and selling four.

One was taken by British billionaire businessman and founder of ICAP Michael Spencer and his wife Sarah, who built Sirai House. Another was bought by a Nigerian-British businessman who built luxury lodge Arijiju, while George and Lucilla Stephenson bought another lodge called Laragai House; Minnie and Joe bought the fourth share. The aim of Dyer splitting the conservancy was to create more shareholders to protect and provide a secure habitat for the over 50 different mammal species and some 330 bird species (28 of which are endangered), as well as providing employment for over 500 community members along with free medical treatments and education.

But running a reserve such as this is no mean feat, with annual costs of US$1 million-US$1.5 million which they split between them. Tourism fees help considerably. On top of the nightly rate at Lengishu (US$10,000 for six people for a minimum of three nights, plus US$700 per extra person) there is a mandatory conservation charge of US$190 per person per night. It’s a high-end offering for a niche market that doesn’t think twice about the nightly rate, Joe says. It’s a market he is well familiar with, too, as former CEO of JP Morgan EMEA, where he helped some of the world’s billionaires with their finances.

This conservation fee helps with reserve maintenance such as fixing fences, digging roads, building; filling water butts for animals when there is a drought (so far, some 640,000 litres of water have been distributed); and paying the rangers who patrol the reserve constantly to protect black-and-white rhinos, elephants, leopards, gazelles, lions, zebras, buffaloes, warthogs and giraffes that roam its plains on our game drives. One of the key ways to balance the needs of the community with those of the wildlife is the livestock-to-market programme, which allows locals to graze their cattle on Borana, as well as dip them to remove ticks and worm them. We see large herds of healthy-looking cows, goats and sheep on our game drives, but we are told that outside the reserve, the combination of drought and over-grazing is creating tensions.

Now, as the scale of the climate crisis continues to grow, the Dyer family is looking to sell one more share of the Borana Conservancy, at a cost of between US$4 million and US$5 million.

On our last day at Lengishu, we ride mountain bikes into the hills, and suddenly, a flash rainstorm drenches us to the skin. Minnie and Joe are delighted that the drought has broken. As we take our leave a few hours and a hot shower later, and the small green Cessna Caravan rises into the sky, the ground below looks darker, vital, anticipating life. For the animals and the people of the Borana Conservancy, it feels a hopeful note on which to go.

3 nights Lengishu - All Inclusive + Including flights from Nairobi $36,420 USD / £30,350 - 3 nights, 6 people, including internal Kenyan flights and Nairobi transfers.

Travel Jan-Jun, and Oct-mid Dec.

https://www.lengishu.com/

*Lengishu has a minimum stay of 3 nights.

To book please contact:

https://www.theluxurysafaricompany.com/ or call on +44 1666 880 111

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Luminaries Issue, Summer 2022. To subscribe, contact