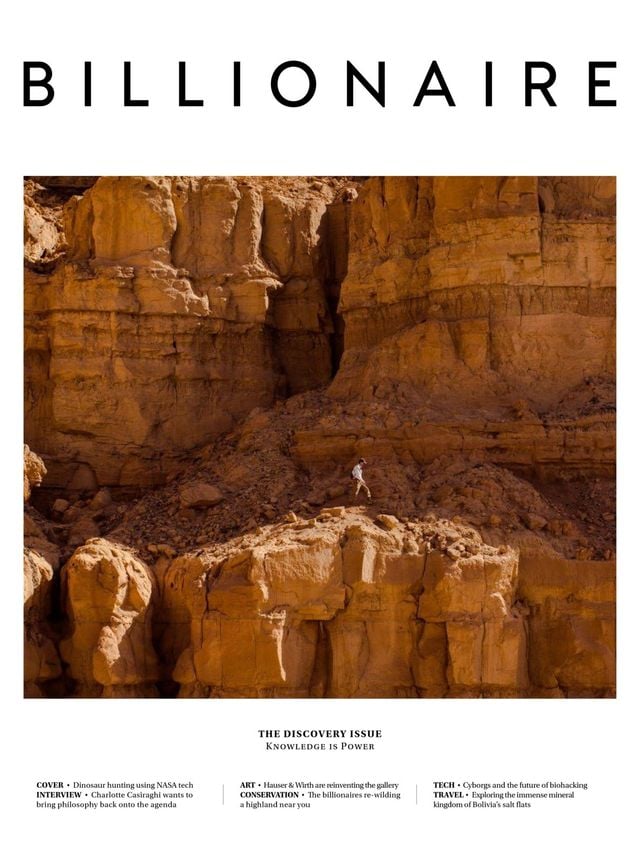

Bolivia: Salt Of The Earth

The Bolivian Altiplano offers spectacular and vividly coloured vistas.

Leaving San Pedro de Atacama, Chile, one looks up towards Licancabur, the ‘mountain of the people’, a 5,916m-high extinct volcano on the border with Bolivia. Its shape is the epitome of what a volcano should look like, suggesting great adventures and unspoilt landscapes ahead. Up 2,000m, the Chilean tar road transforms into a heavy dirt road; the air gets even thinner as we approach Hito Cajón border control at 4,480m. All around us, the desolate altiplano of South Lipez fills the horizon with bold colours: ochre, ferric red, purple and intense white.

White and intense altitudes, as it turns out, will be the common denominator of our road trip. In this mineral kingdom the size of Israel, white continuously plays a trompe l’oeil effect: everywhere seems to suggest snow when it is, in fact, salt. Salt covers the edges of crimson-red lagoons flocked with red flamingos. It concentrates around Laguna Verde, enhancing the luminous green-turquoise colour of the water, due to high concentrations of carbonates combined with dissolved heavy metals, including copper, arsenic and lead. Salt emerges from the rims of Sol de Mañana, one of the highest geothermal fields on the planet: boiling mud pots and steaming fumaroles, clouds of steam and a smell of sulphur, add a surreal feeling to this sky-high plateau.

The more we travel north, the more apparent the salt becomes, until we reach, in awe, the fringes of the Salar de Uyuni, the biggest salt flat on the planet (10,582 square kilometres). Left behind by prehistoric lakes evaporated long ago, a thick crust of salt extends to the horizon, covered by quilted, polygonal patterns of salt rising from the ground through evaporation. In the middle of these endless, blindingly white, surfaces a few islands protrude: stunning Incahuasi island brings life back into the picture with its cacti-covered rocks. Thousands grow under the harsh sunlight with their enigmatic, sometimes human-like silhouettes. A fragile ecosystem, the Salar has been under attack for several years now: holding the Earth’s largest sources of lithium (a crucial component of the lithium-ion batteries that power cordless tools, electric vehicles and portable electronics, including cell phones, laptops and cameras) it is heavily mined. In the dry season, the salt-crusted surface remains one of the world’s natural wonders: every day, as the sun rises and sets, the sparkling salt turns to ethereal yellow, pink and blue light on the edges of every hexagonal salt tile.

When harassed with salt, we stare at the immense skies. Up there, clouds have a shape of their own: lenticular clouds hang immobile above rock formations, while others paint the intense blue sky with heavy white brushstrokes. The sceneries become more striking as they seem to be bearing messages.

Along the road, we discover another atmospheric anomaly: penitentes, named after their resemblance to a crowd on kneeling people doing penance. At first, we look at the strange-sculpted white figures that stand above the orange desert thinking they are salt blocs carved by erosion. The air is brisk around us, but the sun warm. To our surprise, we walk up to fields of poetical statues sculpted out of snow: aligned, the elongated thin blades of hardened ice point in the direction of the sun. Without melting.

On the Bolivian altiplano, geology and natural phenomenon really have a life of their own.

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Discovery Issue, September 2018. To subscribe contact