Deep Diving The Titanic Shipwreck

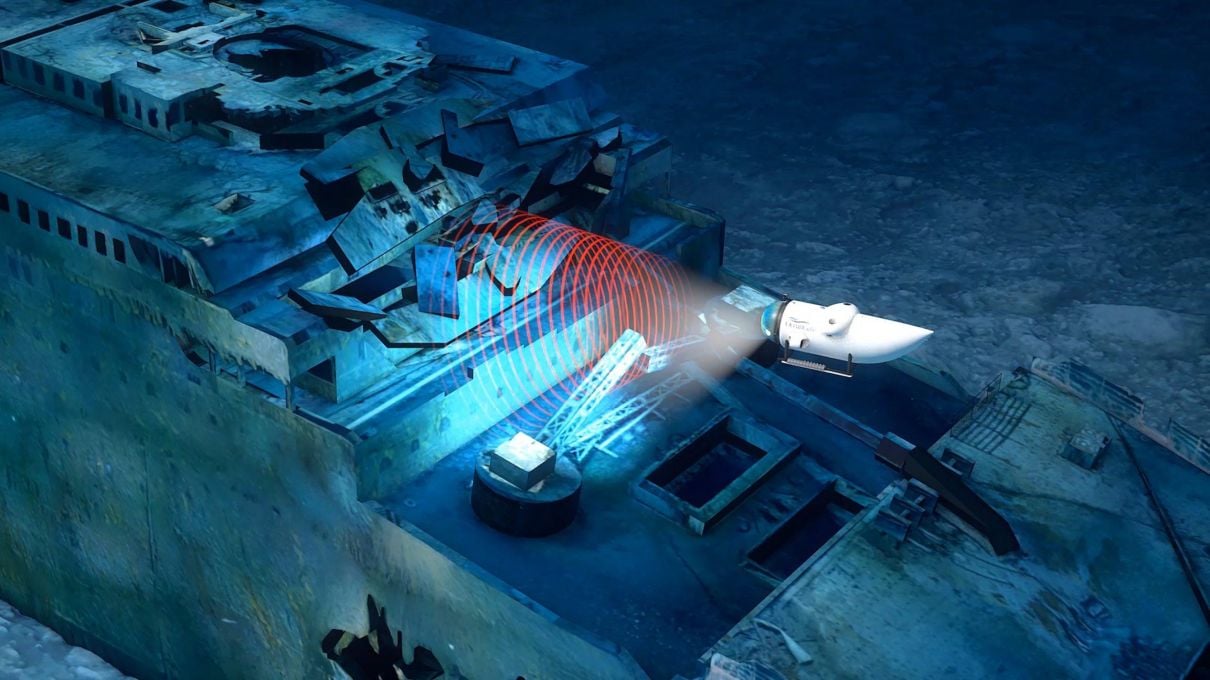

A submarine trip down to the sea floor promises a chance to get up close with the most famous shipwreck of all: the Titanic.

With tickets for the journey at US$100,000 a head, one might expect more comfort. But for those ready to put up with a bumpy helicopter ride out into the changeable Atlantic Ocean off Newfoundland; spending a few nights on a working support ship; and being crammed into a small submersible that will take them down some 12,500ft to the sea floor, it will all be worth it. Laying there, broken in two, will be the most famous shipwreck in history: RMS Titanic.

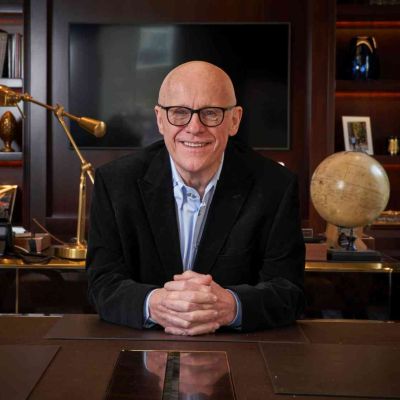

“While it’s safe, there’s a sense of taking this vehicle down to places where perhaps we shouldn’t really be,” says Henry Cookson, head of Henry Cookson Adventures, the company that has arranged the coming dive this summer. “Just going down to the sea floor, surrounded by thousands of tons of pressure, would be adventure enough. But, you know, the Titanic is the big one.”

Indeed, fascination with the Titanic verges on obsession: the Titanic Museum, a long way from sea in Branson, Missouri, receives some 700,000 visitors a year; to date there have been some 19 movies made about the ship, as well as countless books and documentaries.

All play to the drama inherent in its incredible story: the ship — the building of which began 110 years ago this year — was deemed to be ‘unsinkable’ but hit an iceberg and went down on its maiden voyage in 1912. This is the ship that carried only sufficient lifeboats for half the passengers; whose passengers included some of the richest people in the world at the time; that ignored warnings of ice from the SS Californian, just five miles away; and which, through a series of tragic misunderstandings and circumstances, was then unable to call said ship to its aid.

And then there are the inevitable conspiracy theories that periodically refresh interest: did the captain ignore iceberg warnings in pursuit of the Blue Riband record for the fastest trans-Atlantic crossing? Did, as has been suggested by evidence that has come to light only in recent years, the Titanichave a fatally weakened superstructure thanks to a fire in one of its coal bunkers before it even set sail from Southampton? Was, in fact, theTitanic its sister ship Olympic : which its owners are said to have wanted to scuttle for the insurance money after a previous claim, for a collision in harbour, had been rejected?

“There are other wrecks that, arguably, are more important. There are wrecks that are better preserved or more visually striking. There are others — not many — whose sinking led to a greater loss of life. But,” says Stockton Rush, “there is only one Titanic, something we’re reminded of time and time again. The facts of the story in themselves are just amazing, without all the media interest and the Titanic’s place in popular culture. More people reach the top of Everest every day than have ever visited the wreck of the Titanic.”

Rush should know. He’s the CEO of OceanGate, a submersible operator that is making these exceptionally rare dives possible; rare because of growing limitations to visiting what is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, following the organisation’s efforts to limit attempts to salvage from the wreck; and not least because OceanGate has one of just four non-military submarines in the world capable of reaching such depths. Not that the coming dives will be without a spirit of investigation.

“The big issue is how quickly the wreck of the Titanicis decaying, and some say it will be more or less gone in 20 years’ time,” says Rush, who will be piloting the submersible. The dives will also be taking a closer look at the ship’s largely unexplored debris field: analysis of this even just last year has suggested that theTitanicbroke its back on its descent to the seafloor rather than on the surface, as has been claimed to date. Bodies have long since decayed but it is in this field where personal effects are, eerily, distressingly, most readily seen, although, says Rush, “there’s no shortage of rumours of bags of gold waiting there for someone too”.

Indeed, he considers the coming dive to be expressive of a new era in privately funded ocean exploration. “If you look at James Cameron, Richard Branson, Eric Schmidt, the Packer family, it’s these ultra-wealthy people who are spending more on ocean exploration now than, say, the US government. They’re the ones really driving the change in interest, as happened at the turn of the 20th century with Shackleton and the like.”

This is, in part, why he expects the dive to the Titanic, as unusual as it is, to lead to the exploration of other undersea spectacles: oil platforms in the Gulf of Mexico; Second World War wrecks such as USS Lexington, which sank during the Battle of the Coral Sea; the USSIndianapolis, which sank on a secret mission to deliver the atomic bomb; or phenomena such as undersea thermal vents or certain species of shark about which little is known.

“I’m fascinated by how fascinated people are by the Titanic. There’s the suggestion that it’s morbid, but I don’t agree. For some it’s a tale of romance, but for others one of great hubris,” says Rush. “But there are other wrecks [now identified] with their own incredible stories too. Yes, people have their primal worries about submarines but our perceptions of them are changing and of the experiences they can bring. The ocean is an amazing place, but little understood. Ask people what the average depth of the ocean is and most have absolutely no idea.”