The New Electric Frontier

On land, sea and up above, electric motors continue to make great strides.

“For me the impact of this is going to be as big as the internet,” says Ian Foley, “because this is going to affect all forms of transport and there’s an urgency to replace all forms of transport right now. And what makes the progress all the more impressive is that, unlike realising a dot.com idea, developing hardware typically takes years.”

Foley is the managing director of Equipmake, an engineering firm that has developed a power-dense EV (that’s electron volt, or electric) motor. Indeed, his company is now supplying electric engines of various sizes and power to super-cars, city buses, space rockets and even a flying taxi company with passenger-carrying vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) drones. Nor is it alone. An innovative, well-funded start-up mentality is set to see electric power (which is moving away from a dependency on rare metals towards the use of gold ‘nano-wires’, sodium-ion and even the wonder material graphene) change the way we drive, sail and fly. Even, for some alleged grown-ups, the way we scoot.

“There are certain hurdles to overcome before electric fully takes over from the combustion engine, but given its lack of emissions and that it’s quiet and reliable, the electric engine is going to be a game-changer,” says Foley. “Developing these engines has been like shovelling jelly uphill for years but now we’re about to really see things happen.”

LAND

“As far as cars go, the combustion engine is already dead,” says Robert Palm, CEO of automotive design house Classic Factory. “Now it’s just a matter of time.”

While the market for electric-engine cars to date has been hampered by retail prices and by the range afforded by electric engines, limited to roughly 500km, batteries are rapidly improving both in terms of energy density and, another crucial factor, their weight. Super-fast chargers now allow for, say, an 80 percent charge in 20 minutes; not as fast as filling a tank with petrol, but advancing all the time. Wireless charging, among other infrastructural enhancements, is just around the next bend.

“In fact, what’s required is a new way of thinking about the car more as a clean power source that moves, rather than transport with a clean power source,” Palm argues. “A car’s power plant will come to be considered part of a bigger power eco-system and your home, for example, may use its charge when it’s not needed for the car. Really, the only thing slowing this market now is the thinking of the automotive industry itself, which will require complete restructuring and re-thinking.”

Consequently, it’s not just Tesla overtaking its more conventional, combustion engine-oriented rivals in the car market. Apple, Google, Dyson, tech companies able to set up electric car-making factories speedily from scratch, may well dominate the industry in the years to come. A similar process is already occurring in the super-car market, where start-up brands such as Dendrobium, NIO and Acura are helping to shift attitudes away from notoriously carbon-intensive traditional sports cars. This is not just because their performance is considerably better (the £2.5 million Owl from Japanese maker Aspark will pull 60mph in an eye-watering 1.69 seconds) but because they chime with an affluent audience of younger, more environmentally aware people.

“There’s a sense of a negative perception growing around many traditional super-car makers in their current form, and even the true petrol-heads who once sneered at EV are rapidly changing their minds,” argues Justin Lunny, founder of Everrati Automotive, which undertakes bespoke conversions of classic cars, giving them an electric motor. “Car design needs to follow suit too, though, as one problem remains that most EV cars now available are stylistically so homogenous.”

SEA

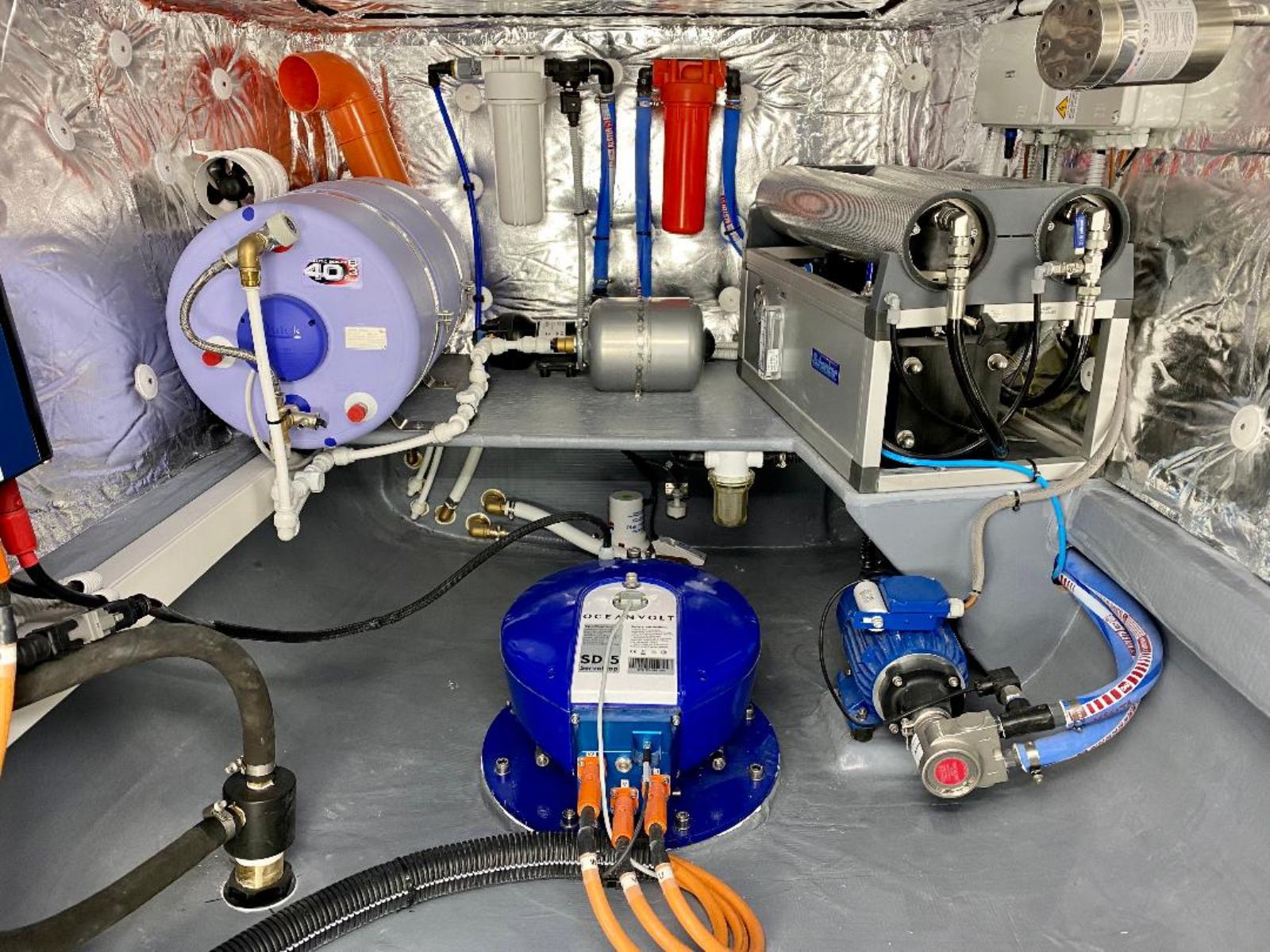

Some boat owners may well be motivated by environmental concerns, but many, says Anna Hietanen, marketing manager of electric marine engine company Oceanvolt, think of an electric engine as simply more fitting to the experience of being at sea. “It’s quieter, there are fewer fumes or vibrations, less maintenance,” she explains. “It’s still expensive. You have to pay more up front but it’s more economical in the long run.”

Indeed, smaller yachts are already seeing a spate of conversions from diesel to all-electric power plants, with a modern lithium-ion battery bank rechargeable through a combination of wind generators, solar panels and even a free-wheeling propellor. Instant delivery of drive also gives the advantage of more control, with electric engines taking up less space than diesel too.

But, given the ever-present issue of the range limited by electric power alone, larger modern yachts are increasingly opting for a hybrid engine. In 2017 Dutch yacht-builder Heesen launched the first super-yacht with hybrid power and has since delivered its second. But the innovation in these vessels is not just in their engines: advances such as fast displacement hulls made from lightweight aluminium and Hull Vane technology (an underwater wing that improves performance) play their part in giving the emissions-free power-plant maximum efficiency. Feadship, another super-yacht builder, aims for all of its launches to have hybrid power by 2025.

Take-up within the yachting community has been slower than hoped for, if only because it’s a conservative world. But, reckons Hietanen, growing environmental regulations regarding the use of diesel on some waters, such as the freshwater US Great Lakes, is proving a convincing incentive to many.

AIR

Late in 2019 a retro-fitted de Havilland Beaver belonging to Harbour Air, a North American seaplane airline, took silently to the skies. This was the debut flight of the world’s first all-electric commercial aircraft. And, says Roei Ganzarski, CEO of Magnix, which developed the engine able to take around six passengers up to 1,000 miles, it marked the beginning of “the third age of aviation”; not least because electric is cheaper to operate per flight hour, “and that means lower ticket prices for passengers”. A more recent 30-minute flight of a retro-fitted Cessna cost just US$6, as opposed to US$240 using aviation fuel.

MagniX is now working with Eviation Aircraft on the development of Alice, an all-electric aircraft expected next year. Rolls-Royce too has its ACCEL project, with the aim of setting the world speed record for an electric aircraft. EasyJet is working with Wright Electric. Indeed, conscious perhaps of the bad press that aviation gets with regards to climate change (it currently contributes 3 percent of global annual CO2 emissions, although this figure is rising rapidly) major aircraft manufacturers such as Airbus are experimenting with how electric power might be used to take more people over longer distances.

An electric trans-Atlantic flight, however, probably isn’t likely within the next few decades, unless there’s a radical leap in battery density. Kerosene remains some 14 times more energy rich than the most advanced batteries to date. Batteries, unlike the jet fuel that gets used up as a flight proceeds, are also prohibitively heavy, and you’d need a new generation of insulation for electrical components too. But almost half of all flights are under 500 miles, so mid-sized hybrid aircraft are likely to be the next step.