Bohemian Rhapsody

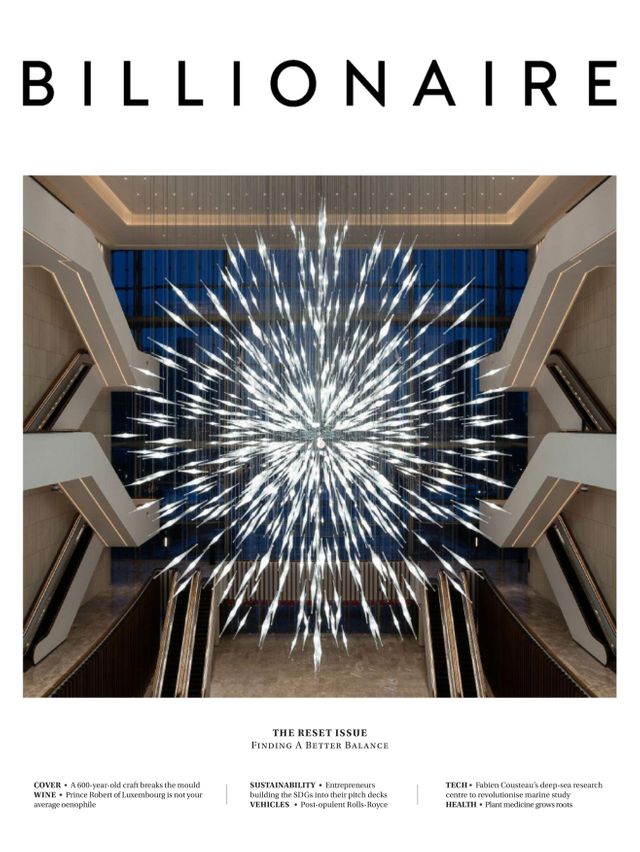

Lasvit has transformed traditional Czech glassmaking into a dazzling new art form.

If you are well-connected enough to be invited aboard a particular Russian billionaire’s new 145m superyacht, you will hardly fail to notice the dazzling artwork at the yacht’s entrance.

A spectacular 17m wonder of handblown glass designed by Marc Newson CBE, the work (whose design remains fiercely guarded) was engineered in the Bohemian workshops of Lasvit, a Czech Republic-based designer and manufacturer of bespoke lighting, rooted deeply in tradition.

Today, Lasvit lighting installations shine in 2,200 hotels, private residences and superyachts, using the tradition of the oldest of glasswork methods — Chřibská 1414 — of fire, wood and hand craft.

To understand Lasvit, one first must understand the history of the region. For centuries, the borderlands of Bohemia have been synonymous with the thriving industry of glassblowing. The oldest archaeological excavations of glass-making sites in the Czech Republic date to around 1250.

But it was at the start of the 20th century that Czech glassmaking gained rock-star credentials. Designers such as René Roubíček, Stanislav Libenský, Jaroslava Brychtová and Vladimír Kopecký were creating ground-breaking works; 20th century Czech crystal chandeliers hang, for example, in Milan’s La Scala, in Rome’s Teatro dell’Opera, in Versailles, in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg and in the royal palace in Riyadh.

But after the Second World War many craftsmen were forced to leave their homes and abandon everything. “The bond of passing the craft from father to son was severed,” says Martin Sikola, a lifetime glassblower and vice-president at Lasvit, in a documentary called BreakPoint.

The decline continued when communists nationalised the family-owned glassworks, replacing them with factories. When the Velvet Revolution brought the overthrow of the regime in 1989 and craftsmen regained their freedom, they gradually began to come out of the shadows. But the long isolation showed and when the economic recession struck, glassblowing fell by the wayside.

Leon Jakimič, founder of Lasvit, was born in 1970s Czechia with five generations of glassmakers in his blood. In his 20s, fresh from a failed tennis career (he admits he fancied himself as “the future Ivan Lendl”), he decided to move into glassmaking.

Channelling his competitive spirit, he had a vision to build the world’s most innovative glassmaker. “I set out to be number one,” he says.

But his first attempt at bringing Czech glassware to the international market was a flop. He was unable to understand why the classic ornate chandeliers of yesteryear were not selling abroad.

Ultimately, it was a meeting with international design consultant Stephan Hamel that provided him with the first spark of innovation. “I met Leon in Beijing, he showed me a catalogue and asked me my opinion,” says Hamel. “Trying to be an honest guy, I told him: this collection is really horrible.”

Taking the criticism on the chin, Jakimič asked for advice. Hamel introduced him to a visionary Czech art director, Maxim Velčovský, who Jakimič persuaded to join him.

So it was that in 2007 Jakimič branched out, with the backing of an angel investor friend and two other colleagues to set up Lasvit. His aim was to set a new international bar for Czech glassblowing, a revival of the phenomenal success of 20th century Czechoslovak glass.

“Leon’s vision was to create something totally over the top, an explosion of a new dimension of attitude of light with glass, like a big bang,” says Hamel. “I wanted to tear up the rule book,” agrees Jakimič, explaining that Lasvit is a combination of two Czech words: laska, meaning ‘love’, and svit, meaning ‘light’.

Lasvit harnessed the vision of an A-list roster of influential designers and architects, including Zaha Hadid, Yabu Pushelberg, Arik Levy, Kengo Kuma, Maarten Baas and Maurizio Galante.

Lasvit’s designs soon became objets of desire collected by billionaires including Petr Kellner, the wealthiest Czech businessman with US$15.5 billion. Commissions came in from ultra-wealthy developers in Hong Kong, Lasvit’s second home outside of Czech Republic, with collectors including Martin Lee of Henderson Land; Ronnie and Adriel Chan of Hang Lung; Adrian Cheng of the New World Group; and Christopher Cheng of Wing Tai, who also bought a ‘Candy chandelier’ designed by Fernando and Humberto Campana: an array of kaleidoscopic lollipop-shaped lights.

In 13 years, Lasvit has grown into a company of 400 located between Czech Republic and Shanghai, with ateliers in Prague, Hong Kong and New York, making hundreds of bespoke pieces a year. Prices range from US$50,000 to US$12 million and annual turnover is now around US$50 million. Business, says Jakimič, has not been impacted too much by COVID. “People more than ever want to surround themselves with beautiful, light-filled things at home,” he reflects.

With his tanned skin, precise movements and steady blue gaze, Jakimič still has the air of a tennis champ. We are sitting in Lasvit’s Hong Kong office, an Aladdin’s Cave of extraordinary glass design, for which the company won the prestigious Milan Design Award in 2018.

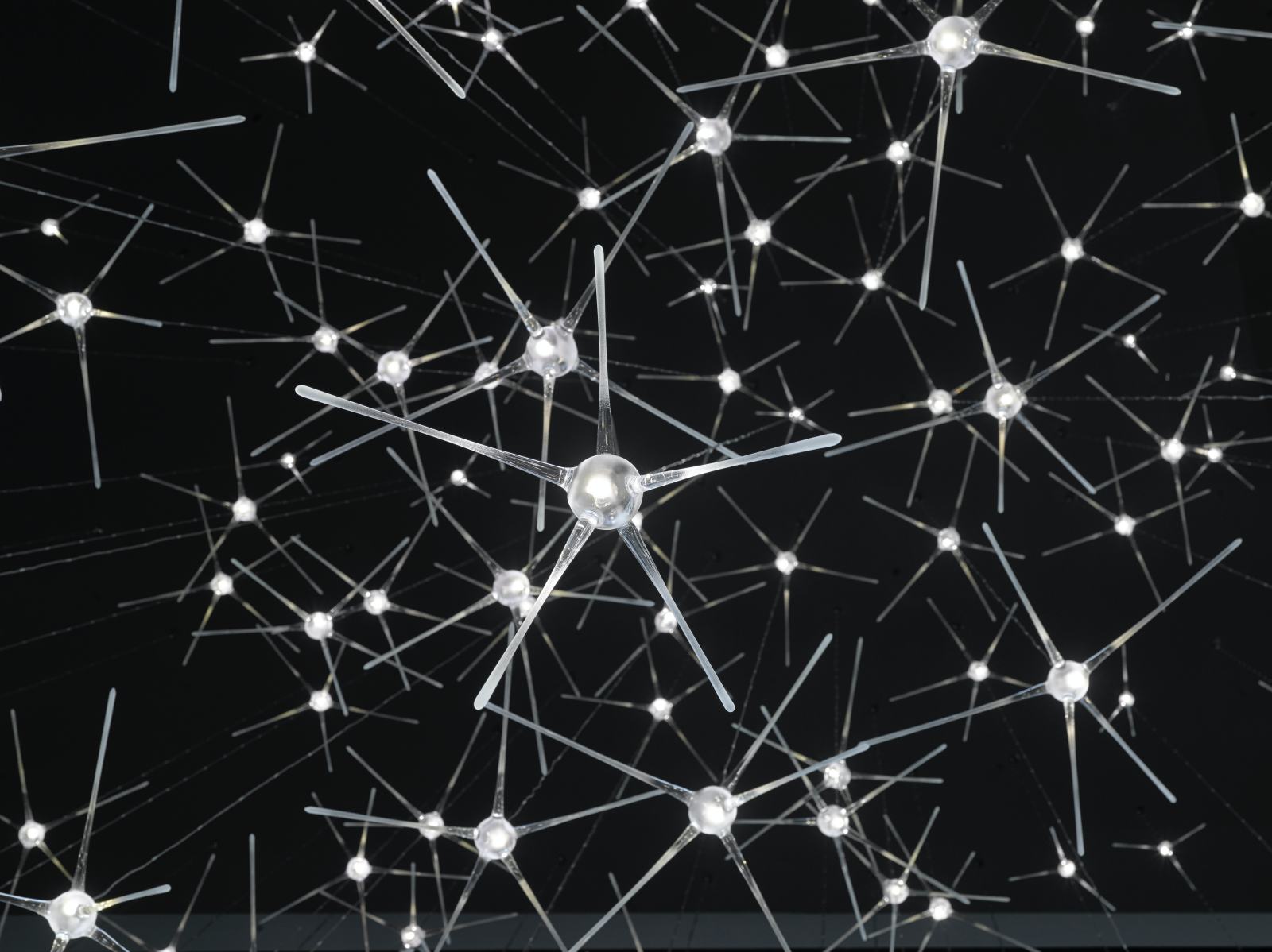

From my seat I gaze up into the myriad depths of a chandelier constructed from 5,000 glass tubes, suspended from the ceiling, reminding me of an ethereal sea creature. Jakimič offers me a glass of water, the glass designed by Kengo Kuma (the designer behind the Tokyo Olympic Stadium) imprinted on the mold of a burned, crackled log: a simple piece at once conveying nature and innovation. He shows me a video of a dynamic glass sculpture in a university auditorium of 328 suspended, star-shaped lightbulbs, which glow in response to music being played. Meanwhile, in South Korea’s tallest skyscraper Lasvit recently installed a sculpture made of thousands of glass spheres to resemble a diver surrounded by bubbles. This type of top-down creativity is what makes Lasvit’s X-factor, he says.

“We only work with true artisans,” Jakimič says. “An artisan uses hand, mind and heart, unlike a craftsman who uses his hand and mind and a worker who just uses his hands.”

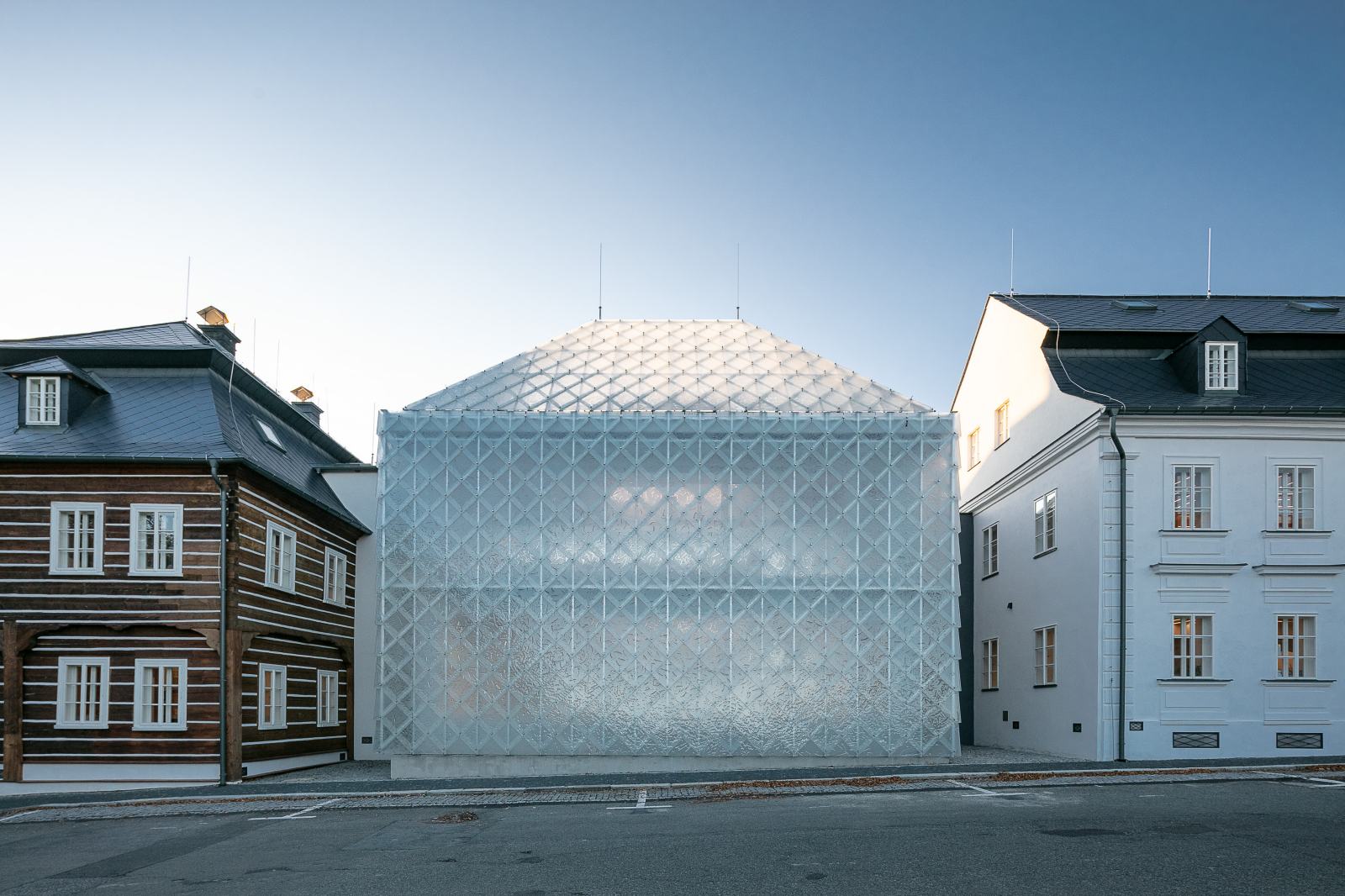

Jakimič recently left Hong Kong to return to the Czech Republic with his family (he has five kids, all with names beginning with ‘L’; his wife’s name is Lucie. “I just have a thing with the letter L.”) in order to grow the business. He will be based in Lasvit’s mind-bending new headquarters on Palackého Square in the Czech town of Nový Bor.

Two hundred years ago, the two timbered houses at Palackého square in Nový Bor were the home of glass workers. Lasvit renovated these historical houses and made them its headquarters. The whole compound also features two modern, newly-built buildings – the Black house and the Glass house – which are a metaphor for darkness and light. This building has already been awarded several times, including the Dezeen Award for the business building of the year.

Inspired by the traditional slate roof shingles of the area, the glass tiles integrate transparency and technology in the local vernacular. It’s a continuation of the glass legacy, says Jakimič.

He also plans to set up a glass museum in Prague, which he hopes will become a major tourist attraction, located at the Neo-Renaissance-style Živnostenská bank building. He sees innovative glassmaking as a matter of national pride after a tumultuous recent history.

“The Czech Republic has many good consumer brands but not really any international luxury brands. I would say we are now the first.”

It is clear, that now is Lasvit’s time to shine.