Hidden Talents

Shiro Muchiri bridges a gap between time-poor collectors and undiscovered artisans.

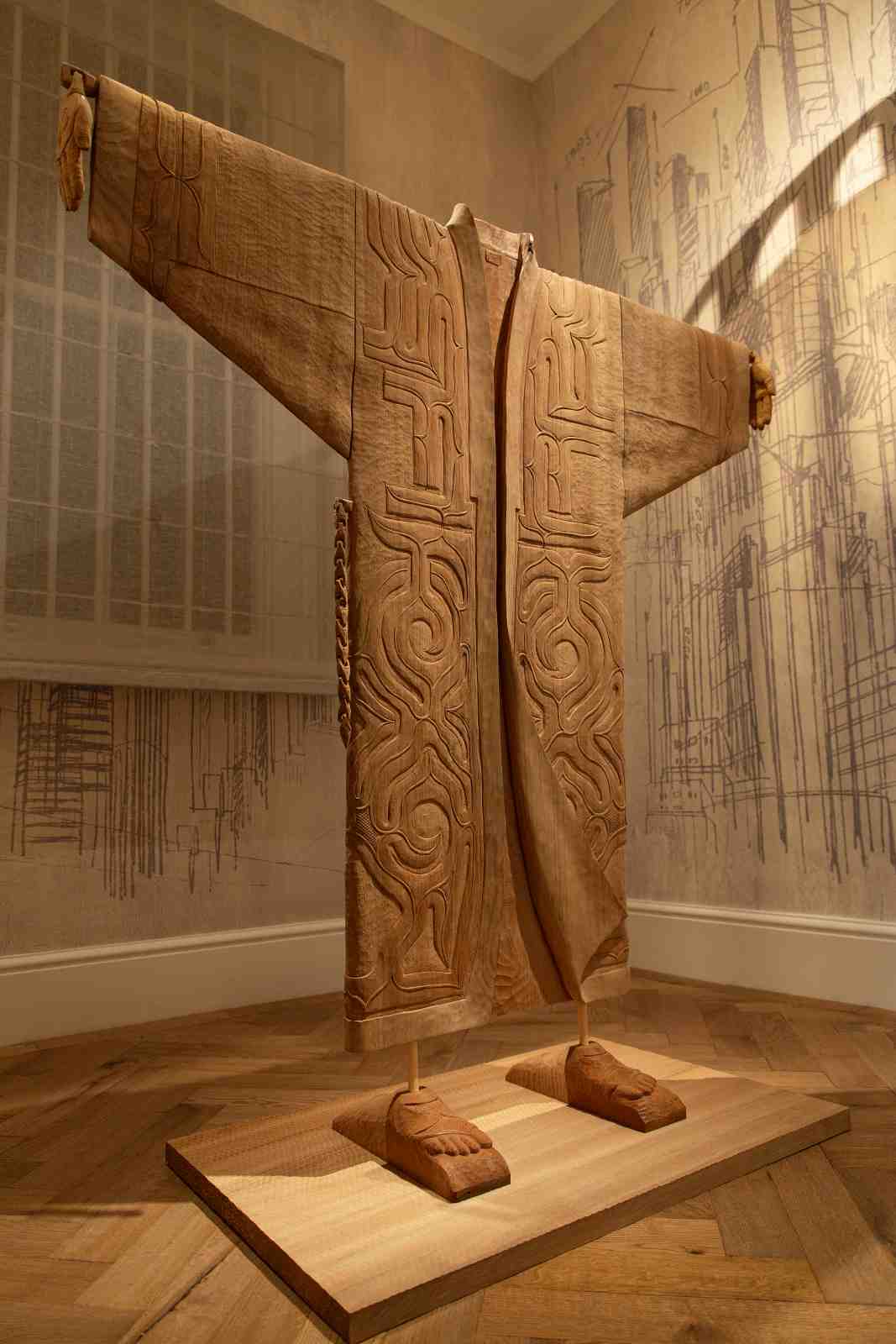

On the Japanese island of Hokkaido, the indigenous Ainu community has its own distinct culture that dates to the 13th century. Its language, religion and culture are distinct to the Japanese, while its influences are rooted in nature, which is apparent in its crafts.

Famed for its carving, traditionally done by the Ainu men (women are known for their weaving), it decorates wood with ancestral patterns. Common motifs include flower buds, rivers, spirit gods (kamuy) and ramu-ramu, salmon scales.

The pool of master carvers is now relatively small. However, three years ago the government created the Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park in a bid to help preserve the Ainu culture.

This is where Shiro Muchiri comes into the story. An interior architect born in Nairobi, Kenya, trained in Milan and working globally over the last two decades, Muchiri delights in the discovery of artists and artisans with a long-standing traditional trade, introducing them and their work to time-poor art collectors.

“We try to give artists new platforms and visibility, while evoking the human story behind a product,” she says.

When Muchiri heard about the efforts, she got in touch with the director of the Nibutani Ainu Culture Museum to find out more. From there she was introduced to Toru Kaizawa, Ainu master carver, who has worked in his trade, learned from his father. “His work has achieved prominence and is in the British Museum, for example, but he said while he appreciates his work being archived, he wants it to be used and celebrated in today’s environments.”

Muchiri commissioned a motif from Kaizawa and his brother for use in designs. Other commissions included a unique tea set, carved door handles for a cabinet, a wooden kimono and owl’s eyes for ceramic homeware. “For the art world and community to understand the Ainu, I wanted its work to be portrayed in a contemporary way rather than an indigenous format, which you might see in a glass box in a museum,” she says.

Muchiri is showing the pieces at her gallery which opened in 2020, a beautiful five-storey townhouse, in Marylebone, London, called SoShiro. She says: “Inclusive art commissioning is a powerful tool in creating social and economic value and supporting meaningful connections between people and place.”

Of the now 25 artists she works with around the world (others include a Kenyan workshop that specialises in beading; and a Saigon-based artisan) many collaborations are with artists who have been well-established for years, but still lack collecting prominence.

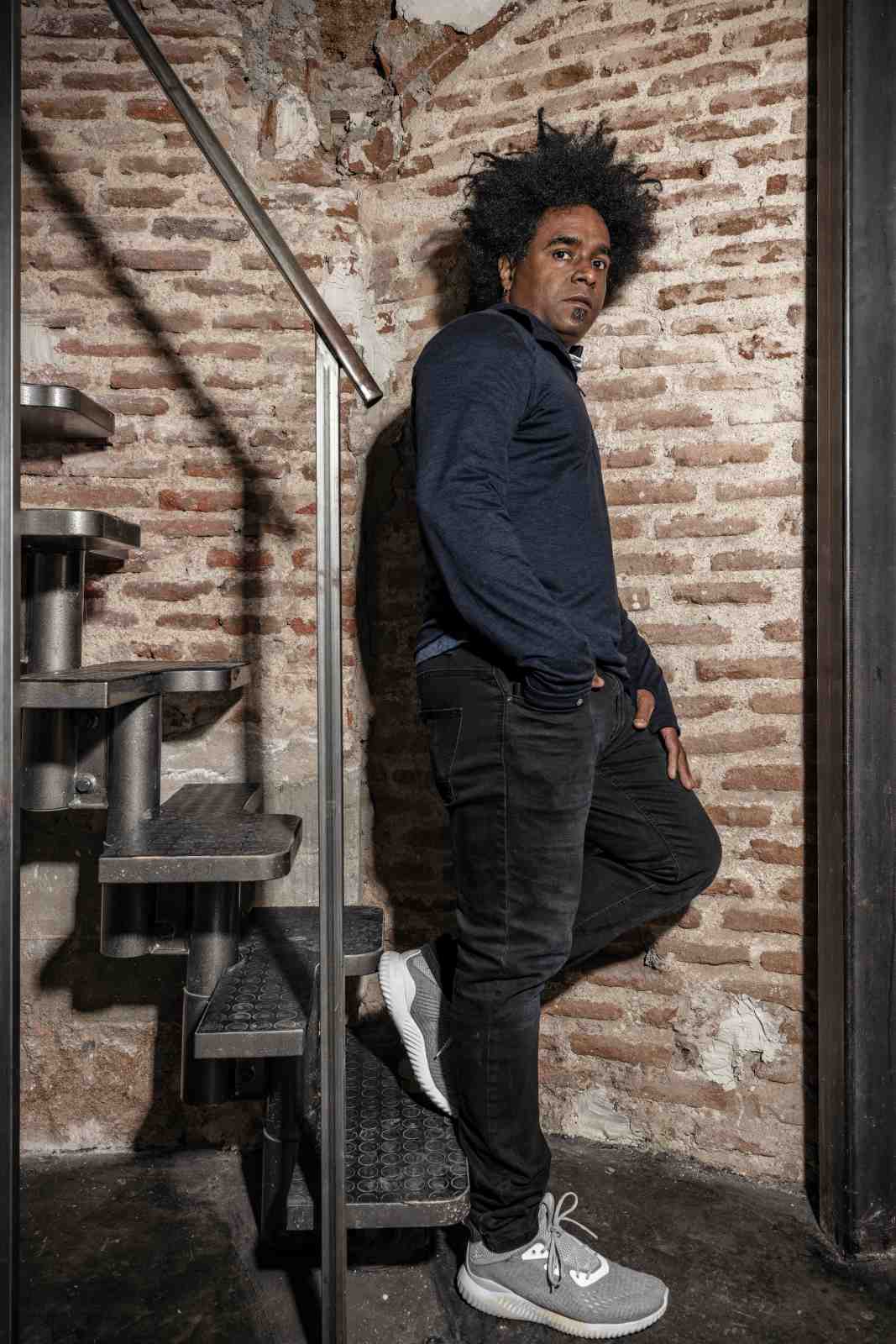

Alexandre Arrechea is a Cuban visual artist who has worked as an artist his entire life and has had work acquired by the New York Museum of Modern Art for its permanent collection. He was approached by Shiro to collaborate on furniture pieces on which he transposed some of his work to. He is known for his photo montages of buildings in Havana, creating a colour palette of the Cuban capital, ranging in hue as political influences changed, from Soviet to Spanish.

Arrechea says working with Shiro was an effective partnership. “As an artist with a long career, there’s a quality that I value above all else, and that’s a willingness to take risks. When I joined Shiro’s stable, I immediately noticed this trait in her and the platform she was building.”

He adds: “This quality, combined with her work methodology, is rooted in the concept of exhaustive research on various materials and their potential when collaborating with high-end crafting professionals. The goal is to make a difference and bring the artist’s vision to life. Shiro is constantly travelling in search of the right places for production, all while providing artists with the space and freedom they need to deliver their work and learn from the process.”

Many people talk about art as a transformative cultural force, but few properly engender it. With gallerists like Muchiri, and her desire to connect artists and artisans from diverse backgrounds, it lends a whole new meaning to the creative practice.

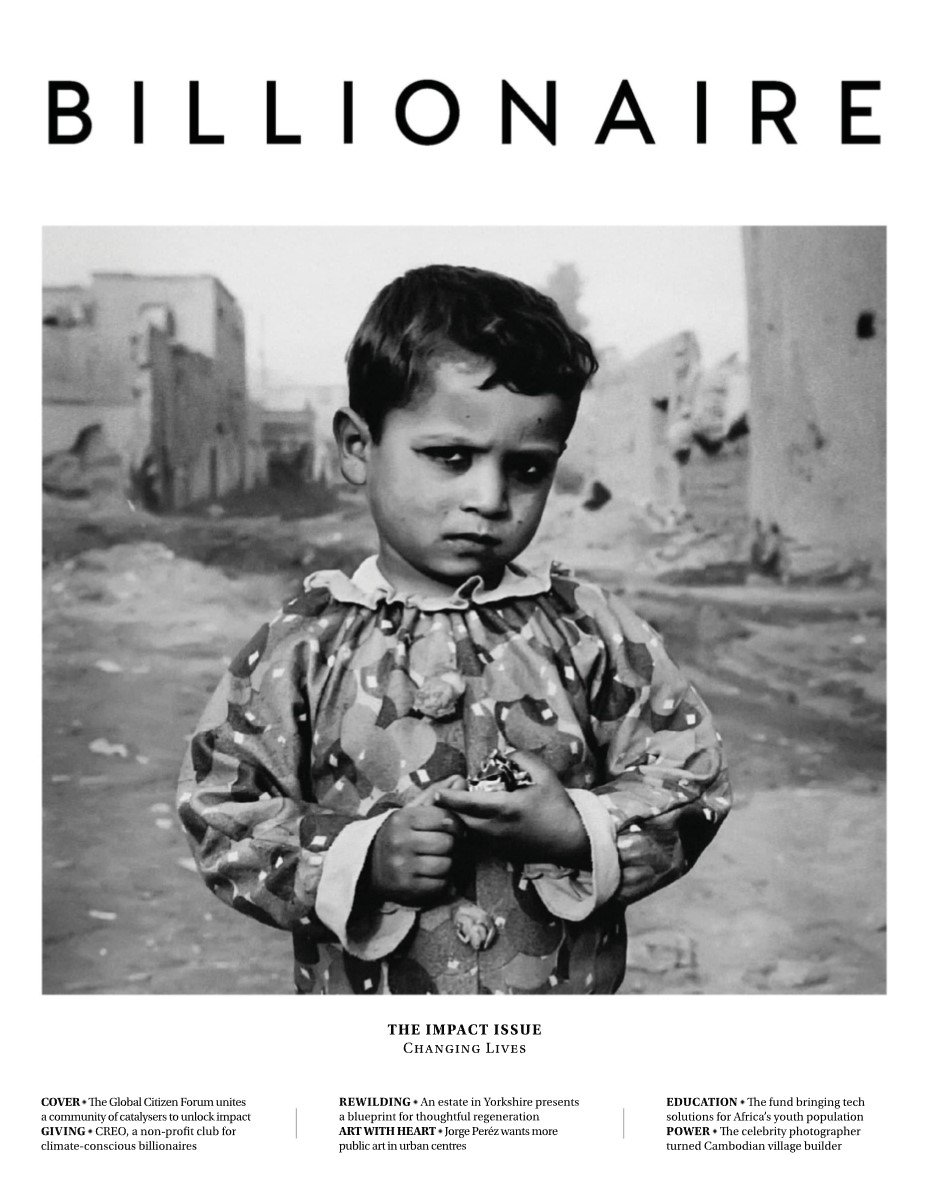

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Impact Issue. To subscribe, click here.