Healing Architecture

Jacques Herzog believes in a noble cause of therapeutic buildings.

Jacques Herzog, one half of the Pritzker Prize-winning architectural powerhouse Herzog & de Meuron, is a passionate cyclist. And one knock on effect of pandemic-induced delays is that he is still waiting for his new racing bike to be delivered.

Herzog’s daily commute to the office from the home that he built near Basel is to ride over the near-vertical Swiss Alps. “Every day I race myself, I’m so impatient,” he says, dressed in a black beanie, big glasses, white T-shirt and casual suit. Wanting to smash his personal best, he ordered a stunningly speedy Italian racing bike about 18 months ago but, with supply-chain issues, it has been delayed and delayed. “But, actually, with COVID we have never been busier, work-wise,” adds Herzog.

We are speaking on the site of his latest project to come to fruition: the new campus of the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London’s Battersea. A distinct addition to the south London skyline, the 15,500-square-metre space combines irregular brickwork, sculptural recycled aluminium ‘fins’ and cavernous interior spaces. Specialising in postgraduate art and design, former students of the RCA include Barbara Hepworth, Sir Ridley Scott, Thomas Heatherwick, Tracey Emin CBE, Sir Peter Blake, David Hockney, Sir David Adjaye, Zandra Rhodes and many more. With an alumni as revered as this, no wonder the new campus is almost exclusively furnished with its names and logos: Tip Ton chairs by Edwards Barber and Jay Osgerby for Vitra; Arc stools by Jemma Ooi and Nathan Philpott for Custhom; an E8 table by Mathias Hahn; and Sam Son chairs by Konstantin Grcic. On the wall, a bright, off-kilter painting by Chris Ofili lights up the room (he made it as a student at the RCA).

University campuses are not often skyline-changing buildings, but the £135 million in funding raised for the RCA’s transformation was completely extraordinary. The new building was made possible with an unprecedented grant of £54 million from the British Treasury back in 2016, as well as match-funding support from various philanthropists, including a £15 million gift from the Sigrid Rausing Trust, founded by the generous Swedish philanthropist. The Rausing Research & Innovation Building, where our conversation is taking place, is named after her.

The new campus is remarkable, a reflection of how well student representatives, academicians, faculty and architects came together to agree on the best solution for the spaces, says Herzog. He calls it a “porous and flexible territory of platforms” to give “space to change and grow, enabling the transformation of space as needed during the process”. It marks a step change in the RCA’s transformation into a science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics postgraduate university, with a particular focus on ‘future-proofing’: preparing for subjects that will be being pursued 100 years from now, enabling students to tackle some of the most pressing issues of our time.

As well as areas dedicated to art, sculpture, and performance, there will be robotics, computer sciences, intelligent mobility, advanced manufacturing and complex visualisation. There are also public engagement areas, such as a café, for the public to have a good look at what the students are up to. “The ambition is that it is open for collaboration, to share space. This is so important to tell people around you who you are and what you are doing. The horizontal exchange is super important in the time we live in now,” says Herzog.

The magic that Herzog & de Meuron is known for is evident in the tactile nature of the architecture: a sea of playful textures. Herzog points to the irregular brickwork. “I love the roughness and sense of the archaic. Everything in these times seems to be so abstract, so virtual, so much of the world is smooth, shiny and refined. You get a sense of depth, smell and height from these different sensations.”

One of Herzog & de Meuron’s most famous buildings is the Tate Modern, a contemporary art gallery located in the former Bankside Power Station on London’s South Bank. It is one of the most-visited art museums in the world. “It literally transformed London into a city for contemporary art, a playful, experimental, public space, opening up towards the world, whereas before it was more oriented to British art.” Another recent project is the M+ Museum in Hong Kong, which Herzog still has not been able to see due to travel restrictions. “There is no comparable museum in Asia,” Herzog says.

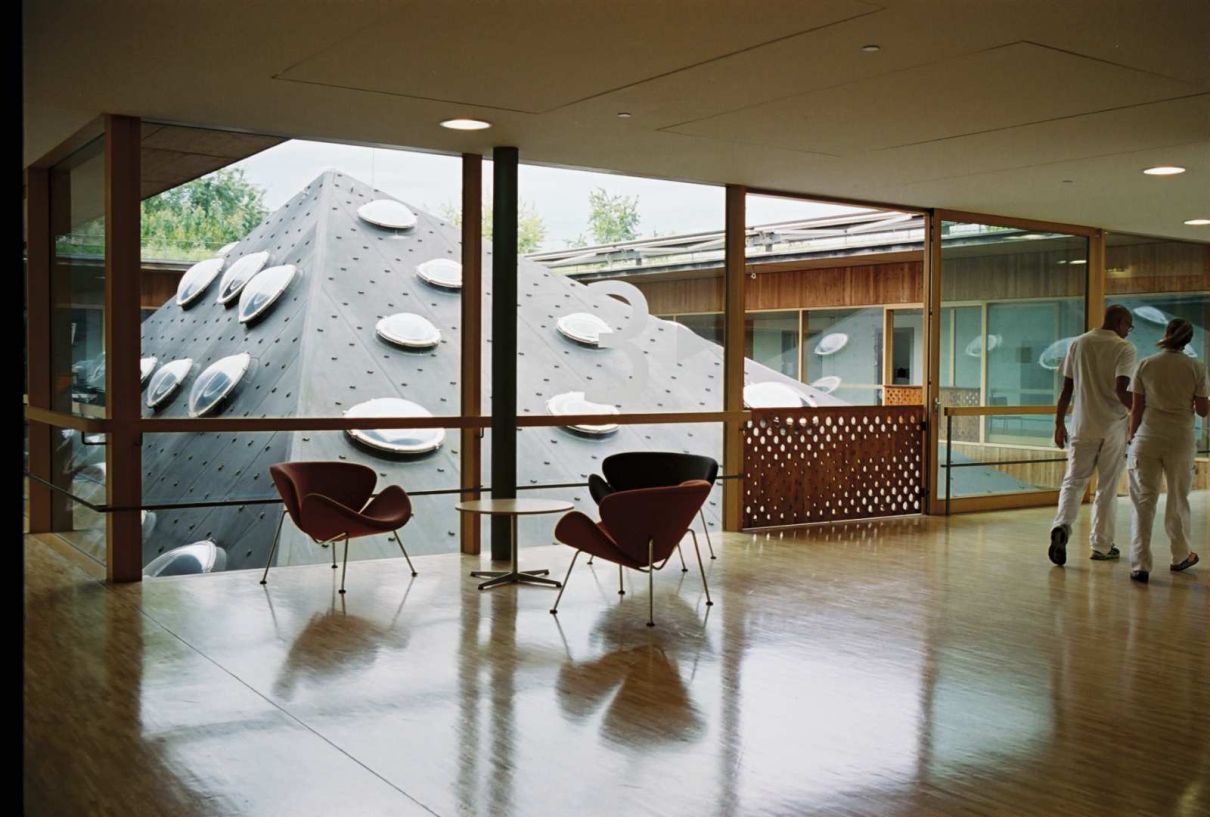

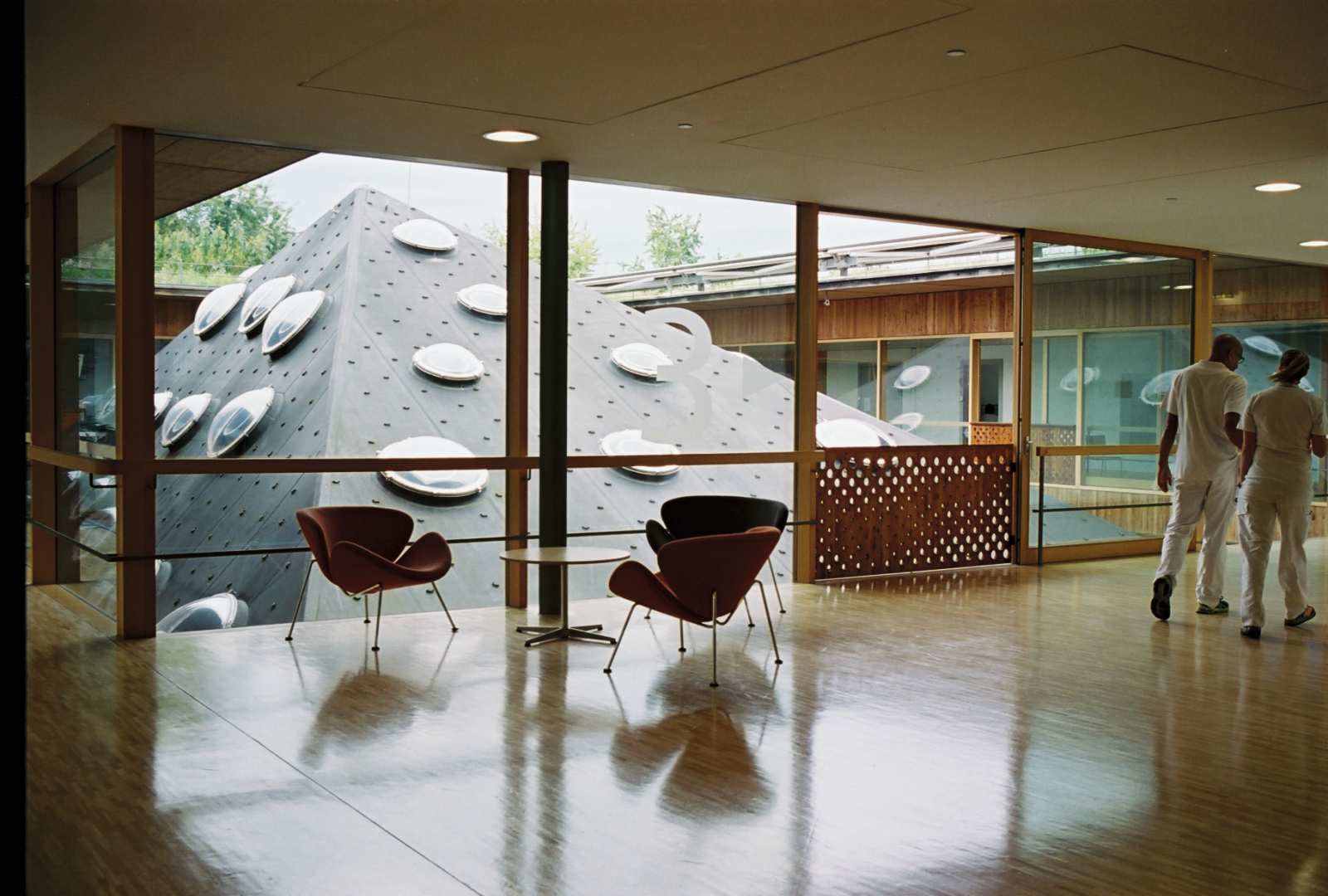

A subject very close to Herzog’s heart is that of healthcare architecture. “We build hospitals that are not like hospitals,” he says. “There is not enough good architecture in healthcare and we wanted to change that. We coined the term healing architecture, before that term was on the table. It’s a big new field,” he adds. Herzog & de Meuron designed the University Children’s Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland, and the New North Zealand Hospital in Hillerød, Denmark, both currently under construction. A new project to expand the University Hospital in Basel was recently awarded after a design competition.

But one of Herzog’s favourite projects was the Rehab Hospital in Basel, which opened in 2002. A beautiful low-rise, indoor-outdoor building with natural materials and vegetation, it is flooded with natural light and built around a series of courtyards filled with water features and trees, designed to be highly therapeutic.

“Architecture affects you,” says Herzog. “When you work in a nice building; when you learn in a nice building; when you are a patient surrounded by beautiful architecture; it makes a huge difference.”

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Luminaries Issue, Summer 2022. To subscribe, contact