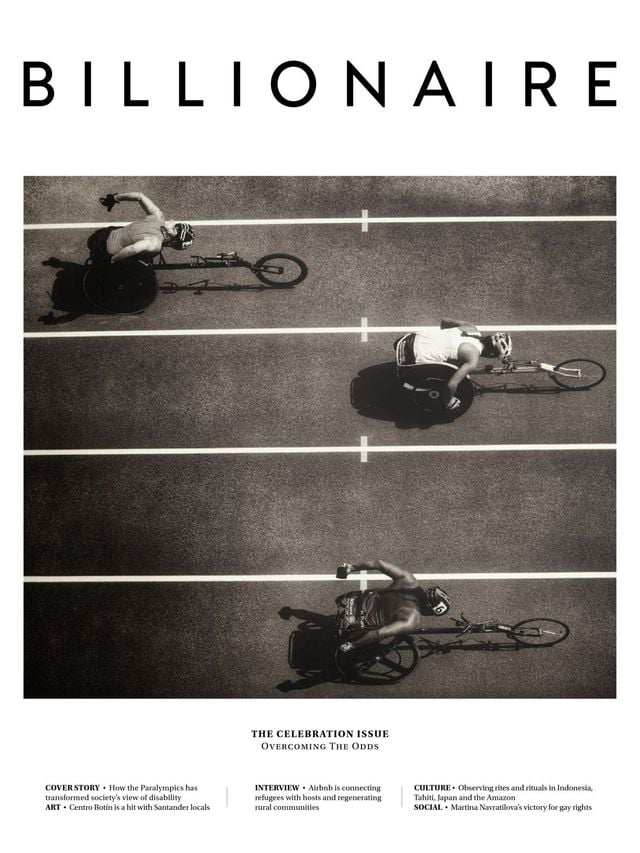

Meet The Superhumans

The importance of Paralympic sport in changing society’s attitudes towards disability cannot be underestimated.

“In the past, people were afraid of touching athletes with one leg or one arm,” recalls Heinrich Popow, a 34-year-old German sprinter and two-time Paralympic World Champion. At the age of nine he had contracted bone cancer, leaving him facing an above-knee amputation. Awaiting surgery in a hospital bed, he was visited by Paralympic racing cyclist Arno Becker. Becker lifted his trouser leg to reveal his prosthetic limb, and promised the boy he would be able to do everything, just as before, although he would have to “work a bit harder than everyone else”.

Because of his vocation, Popow no longer feels disabled. “Paralympic sport changed my life. It gave me the possibility of showing people what we are able to do.” Now Popow is a regular face at hospitals in Germany, giving hope to young amputees, as Becker did for him.

"Disability often becomes a problem because it’s a situation people don't understand, but children don't think that much, it's more society that makes it a problem. Becker's visit showed me the opportunities with my disability, he motivated me to believe in the future by answering all my questions. They can take your leg, but they can never take your passion, he told me," says Popow.

The importance of sport not only in transforming lives, but in changing society’s attitudes towards disability, cannot be underestimated.

Incredibly, more than a billion people — one-seventh of the global population — are impaired in some way, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Of this, 80 percent are located in third-world countries, often among the poor, old and destitute. Even in the rich world, between 50-70 percent of disabled people are unemployed, according to census data, because employers believe that they are unable to be productive. Many are socially disadvantaged, lacking access to basics such as healthcare, education and leisure activities. Many cities are not accessible to their needs and society is not accepting of them.

As for a career, research by Benenson Strategy Group recently revealed that one in three US people would probably not hire someone with a physical impairment.

You might think that, in 2017, with modern technology and healthcare, the number of disabled people is falling. Not so. The WHO believes that disability will only rise, due to ageing populations, an increase in chronic disease, as well as more armed global conflict.

The International Paralympic Committee (IPC), a German-based non-profit, is making it its mission to drive the momentum behind changing attitudes.

“I always say, drop the d-word,” says Sir Philip Craven MBE, outgoing president of the IPC. Gruff, Mancunian and congenial, Craven is speaking in Hong Kong after winning a US$2 million prize for Positive Energy from billionaire philanthropist Lui Che Woo.

The d-word he is referring to, is, of course, ‘disability’. “It’s a horrible, negative term that focuses on what does not work, rather than focusing on the positive,” says Craven, who prefers to use the word ‘impairment’. But he is very familiar with the d-word, paralysed from the waist down as a teenager in a rock-climbing accident. Far from breaking him, the impairment was the making of him, and Craven became a champion British wheelchair basketball player and, from 2001, president of the IPC, effecting a tremendous change in society’s attitudes towards disability.

Under his watch, viewing figures of Paralympic sport have exploded. Last year’s Rio Paralympic Games drew record television viewers of 4.1 billion, well above the 3.6 billion that watched the Rio Olympic Games. This number has more than doubled since the Athens 2004 Paralympic Games, where 1.8 billion viewers tuned in.

The movement is growing roots elsewhere. In 2014 Prince Harry launched the Invictus Games, aimed specifically at wounded and injured war veterans, taking part in sports such as wheelchair basketball, sitting volleyball and indoor rowing races. This year’s Invictus Games in Toronto drew 550 competitors — a record — from 17 nations, competing in 12 adaptive sports. Next year’s Sydney Games promises to be even bigger.

Television coverage and social media sharing has been key to creating momentum. The UK’s Channel 4 has been at the forefront of a Paralympic advertising campaign since London 2012, devising a record-breaking three-minute trailer called Meet the Superhumans. It followed this up with We’re the Superhumans for Rio 2016 which, within four days of its premiere, had been viewed at least 23 million times online. Both advertisements celebrate people overcoming disability in the magnificent and mundane: a man drumming with his feet; a woman with no arms playing with her baby; and a champion footballer brushing his teeth with a toothbrush gripped between his toes.

That the feats of these awe-inspiring athletes are going viral is key to the booming fan base, says Andrew Parsons, the new president of the IPC. “The first reaction that anyone has when they come across Paralympic sport is ‘wow, these guys are athletes, elite performance athletes’,” he says.

Watching Paralympic athletes perform — taking human endeavour to an entirely new level of strength and determination — is almost impossible to do without a lump in your throat. Some of the most heart-warming include young British swimmer Ellie Simmonds OBE, who won four gold medals at the last two Paralympic Games. At age 13, she was the youngest athlete in Great Britain’s team in the Bejing 2008 Paralympics. In the same year, Simmonds won 2008 BBC Young Sports Personality of the Year. Equally inspiring is Canada’s Chantal Petitclerc who won 14 medals in back-to-back Paralympic Games (2004 and 2008), winning the 100m, the 200m, the 400m, the 800m, and the 1,500m races. Although now known for a darker reason, in his prime in 2011, South African sprinter Oscar Pistorius was the poster-child for overcoming disability by becoming the first amputee to win a non-disabled world track medal.

“What Paralympic sport is phenomenal at is showing people what is achievable,” says Danny Crates, the British 2004 800m sprint champion. “It shows that it doesn’t matter what life deals you, you can always make something great out of it.”

With the Winter Paralympics 2018 in Pyeongchang coming up in March, as well as the 2018 Invictus Games in Sydney, Paralympic sport’s star is on the rise.

Since the first Paralymic Games were held in Rome in 1960, the turning point for their popularity, recalls Craven, was Barcelona 1992. “That was a game changer,” he says. “Remember the iconic moment from the Olympic opening ceremony when an archer got his arrow 70ft into the air to light to Olympic flame? Well, Antonio Rebollo, the man who shot the arrow was a para archer, who went on to win silver.”

Barcelona was the first Paralympic Games to benefit from daily live domestic television coverage. Tickets were free and 1.5 million spectators attended. For athletes, this was a new experience. Craven recalls: “They were used to competing in front of a handful of family and friends but they found themselves all of a sudden in front of huge and vocal crowds. They had to get used to that.”

Barcelona’s 1992 Paralympic Games acted as a trigger for the city to improve its accessibility for the physically impaired. The same thing happened in Tokyo and Beijing, where an official government publication after the 2008 Paralympic Games stated that, “now, Chinese people see a person with an impairment as a football player, a basketball player or a track athlete”, says Craven. “It transcends cultures.”

But the key to the change in attitude, says Craven, has been to promote the Paralympics as a competition in its own right, to celebrate what people can achieve, not focus on what they cannot. One of the most important parts of the IPC is its outreach work through its Agitos Foundation. This NGO facilitates and funds national Paralympic committees, competitions and sports in emerging nations through sports programmes in grassroots societies. It sends ambassadors such as Heinrich Popow to deliver education and practical support for athletes and runs campaigns such as I’m Possible: a collaborative programme with member organisations, governments and teachers to promote messages around human rights, sporting values and inclusion to school children.

“Why should it be that people are held down because of a wrong perception?” says Craven. “Our vision is to enable Paralympic athletes to achieve sporting excellence and inspire and excite the world. And we surprise the world; they say ‘wow, I didn’t know that was possible!’ And then you have a chance to make the world a better place.”

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Celebration Issue, December 2017. To subscribe contact