Building Blocks of Hope

Cardano is aiming to revolutionise Africa’s educational and SME system with academic records and microloans.

“I started my company with a dream of delivering economic identity to those who don’t have it,” says 34-year-old Charles Hoskinson, who founded blockchain platform Cardano and its native token ADA, which as of November 2021, is the world’s fourth-biggest cryptocurrency.

Hoskinson has a track record in the industry. He is also one of the eight co-founders of Ethereum, the world’s second-biggest cryptocurrency after Bitcoin.

Hoskinson set up Cardano in 2015, he says in a blog post, with a long-term goal to enter and revolutionise the way business is done to elevate the world’s poorest people. “Cardano has always been about entering the developing world. We really want to focus on the three-billion people who don't have reliable access to financial services. We’re super excited to bring those markets in through identity and through wallets into the cryptocurrency space, and then giving them access to RealFi (real finance) so, for the first time ever, they can participate in a global market fairly.”

The idea, adds John O’Connor, director of Cardano’s Africa business, over Zoom, came from the fact that countries in Africa are sorely in need of a better identity system. With a relatively young and digitally savvy population, cryptocurrency could bypass traditional banking completely and get Africans straight onto blockchain where they can do things such as prove their credentials, get bona fide educational records and apply for financing from investors, without a middle man.

“In the developed world it is easy for us to have an identity, passports, driving licences; it is easy for us to travel, it is easy to prove our credit worthiness, borrow money, get insurance and to process payments. We take this for granted. But when you live in the developing world it is very difficult to prove claims, to send or receive money,” says O’Connor. Microfinance transactions can have interest as high as 85 percent, according to the World Bank.

Half-Irish, half-Ethiopian, O’Connor studied at Oxford where he was surprised that there were no other Ethiopian students. Intrigued, he asked about it and learned that the university did not recognise their credentials, partly as there is a major problem with fake degrees from Ethiopia. “They don’t have enough information about what is happening in Ethiopia.”

O’Connor spent many months in Ethiopia trying to figure out what were the problems and where technology could help, and realised Ethiopia fundamentally has an identity problem. “Technology, blockchain and applications don’t make sense without a digital identity solution,” he says.

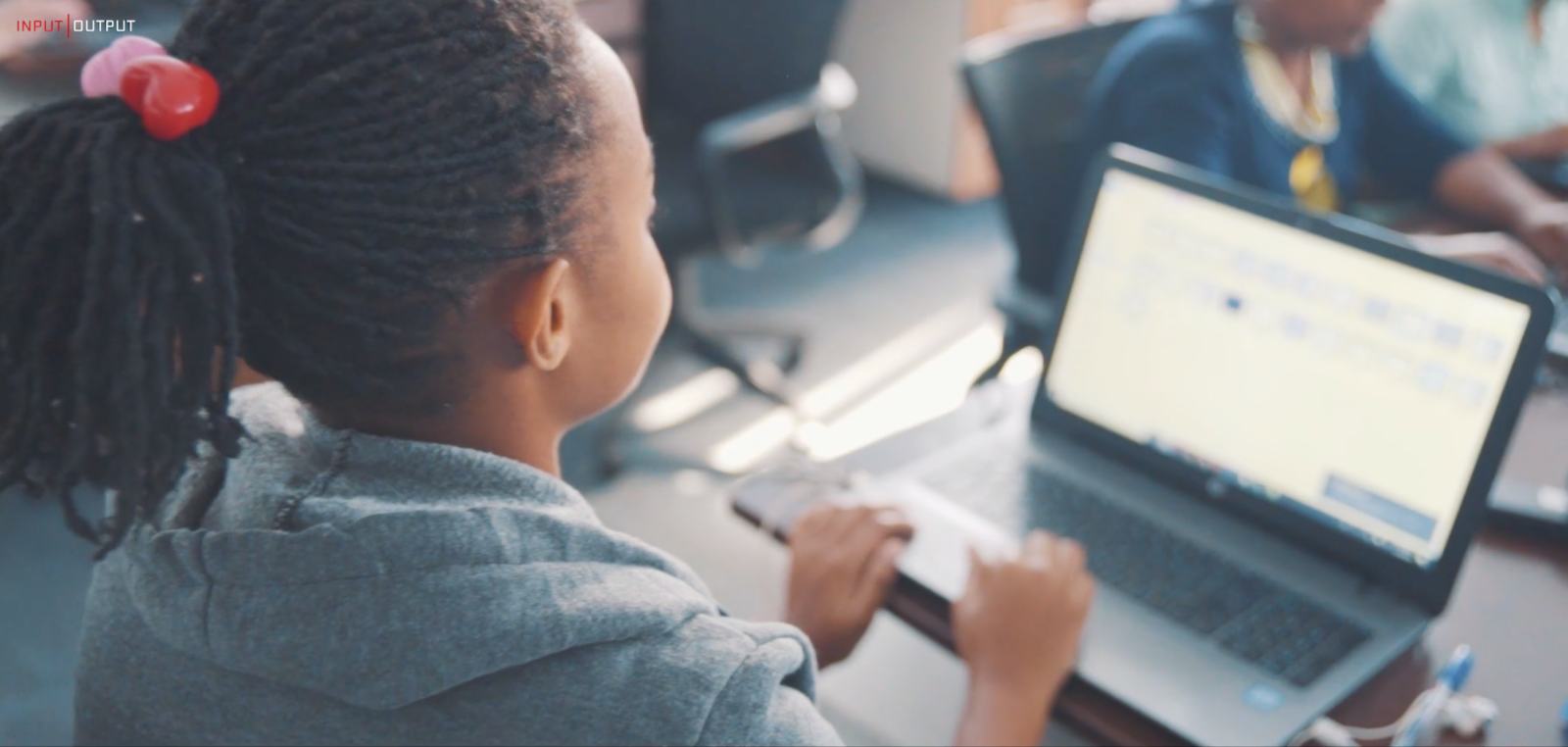

Cardano Africa launched towards the end of last year with an agreement with the Ethiopian Ministry of Education, to register five million student identities and 750,000 teachers on the Cardano blockchain. It is the start of a national attainment recording system to verify grades, monitor school performance, and boost nationwide education. Meanwhile, it has announced a collaboration with World Mobile in Tanzania to connect the unconnected and enable access to essential online services through blockchain.

O’Connor believes that the next few years will see a new age of “on-chain credit activity”, by which he means crypto holders investing crypto in peer-to-peer opportunities. Cardano owners currently hold coins worth some US$80 billion. “Many of them will soon be looking for more yield options, besides staking,” says O’Connor. (Staking is the act of locking cryptocurrencies for a time and, in return, the owner earns more crypto, like a higher yield). “With a validated identity, someone in Rome might have the confidence to make an uncollateralised loan to a coffee business in Kenya, for example,” he says.

Often it is only a small amount of money that stands in the way of an individual breaking out of a poverty cycle, for example, a farmer who lacks a few hundred dollars to double the grain harvest, or a teenager who just needs US$1,500 to pay nursing school tuition fees.

This will all be made possible through having a verified identity. A mature credit scoring system is key to delivering credit, he points out. The reason why banks refuse credit or loans in emerging markets is often that they don’t have enough data about the person or organisation intending to borrow. It is impossible to create an accurate financial picture through a credit score.

But once an identity is created, for example, by linking in utility providers or mobile phone providers to ensure bills were always paid, the data can be presented to a local bank, microfinance initiative or a decentralised pool of capital provided by people invested in blockchain.

“Identity can become an asset in so far as it can be a substitute for collateral,” says O’Connor. “A lender's overriding concern is to ensure that loans, plus any interest accrued, are paid back. One way of enforcing this is by collateralising the loan, but if the lender has enough and clear information about a borrower, if they know the borrower is a high earner, or a long-standing customer, the lender might be more inclined to forgo the collateral.”

As a starting point, Input Output, the holding company of Cardano, has partnered with Pezesha, an Africa-focused digital financial marketplace, to facilitate loans to small and medium-sized businesses.

Although these loans have a default rate of only 2 percent, they struggle for funds in the Kenyan market due to a lack of local liquidity. O’Connor concludes the goal is to build simple friction-free tools: “We see a world where people can lend into real-world opportunities as seamlessly as they do crypto.”