Haute Culture

Biodesign in fashion and architecture is finding its feet as a potential means to lower carbon emissions and support biodiversity.

How would you feel about wearing a fermented jacket, dyed with peachy-pink bacteria pigment? Or a t-shirt printed with graphic algae ink? According to Natsai Audrey Chieza, founder and CEO of Faber Futures, a biodesign firm, clothing coloured and printed with living organisms will become a mainstay of our future sartorial choices.

Biodesign relates to the intersection of biology and design and a burgeoning community of designers, scientists and creatives — a large proportion of them female — who are using organic materials and processes to reimagine the way we build buildings, create furniture or make clothing.

As demand for environmentally friendly ways of production and consumption ramps up, biodesign is becoming more mainstream. Bacterial dyes, for instance, compared to current chemical processes, use some 500 times less water. This is important, as currently about a fifth of wastewater comes from traditional textile dyeing processes.

Naturally, the question at the early stage of a curve is how realistically scalable is biodesign, and how soon can it make a difference?

This is the question Chieza, who recently moved to Norway, seeks to answer through Faber Futures, a company she founded in 2018 that seeks to bridge the gap between scientific advancements and real-world applications through collaborations with biotechnology and creative industries, developing for apparel and fashion.

“The world of materials is a fascinating place to address the climate emergency from,” she says. “For me Faber was forged out of asking, how can we connect what is happening at a molecular level to what the real world needs to reduce its carbon footprint?”

In collaboration with Boston-based Ginkgo Bioworks, Chieza recently launched the first consumer-facing lifestyle brand offering pure biodesign. Called Normal Phenomena of Life, the platform offers a series of prints by Bruton-based artist Kelvyn Smith using carbon negative ink made from algae, as well as t-shirts made from organic cotton screen printed with algae-based ink and face oil made from fungi.

What she’s really proud of is the Exploring Jacket, a unisex smock made from ‘peace silk’, dyed with the bacteria Streptomyces coelicolor, which produces a tie-dye-esque pigment when it ferments. The bacteria need to be ‘fed’ with sugar to produce the pigment; a way to scale the process and keep it zero waste could be to use waste sugar from restaurants in the form of vegetable waste, suggests Chieza. While the jacket does need proper dry-cleaning, the t-shirts can be washed in the laundry as normal.

“This near-zero-waste jacket represents a positive from a biological point of view, that you can scale this type of garment production,” she says. Chieza hopes that soon you could see a mainstream fashion giant like Zara or H&M do a biotech collaboration. She is an advocate for cross-disciplinary collaboration, as well as making her proprietary work publicly available for others to copy and potentially expand. In the pipeline for this year are sunglasses and a homeware range.

London-based Claudia Pasquero is another biodesigner with a knack for cross-pollination. She wears several hats, as co-founder and director of Ecologic Studio; professor of synthetic landscapes at University of Innsbruck; director of the Urban Morphogenesis Lab at The Bartlett University College London; and has most recently focused on home algae-growing gardens called Biombola, which are enormously CO2 absorbent and oxygen-productive. These were inspired by the algae curtains presented as a concept in Dublin during the week of Climate Innovation Summit 2018.

In the pipeline this year is the first collection of products for the living environment designed by Ecologic Studio, including a desktop biotechnological air purifier, a compostable stool and bio-digital jewellery. “The potential of biodesign has become clearer to the wider public in the last three to five years,” says Prof Pasquero. “Biodesign will be essential in rebalancing the planet’s carbon footprint, as it enables a bottom-up ecological process to emerge.”

The future is bright for a new generation of biodesigners and you can study an MA in biodesign and an MA in regenerative design at Central Saint Martins, an art school in London, thanks to Prof Carole Collet, who wrote and teaches the courses.

“The courses we teach are designed to accelerate integration within industry and commercialisation at scale,” says Prof Collet.

As well as teaching, she founded and runs a platform called Maison/0, with a focus on developing regenerative luxury — luxury giant LVMH is a sponsor. “We ask: how can we design for luxury while contributing to restore climate and biodiversity? Rewilding Textiles for instance, explores the viable integration of distinct bio-based dye sources to replace synthetic dyes.” The project combines algae, bacteria and food waste dyes on regenerative textiles — wool, cotton and even nettle — to create a collection of printed and knitted samples that demonstrates the potential.

At the Future Fabrics Expo in 2023, Charlotte Werth, designer-in-residence at Maison/0, expanded the potential of a bacterial printing machine. The collection is printed with wild bacteria on deadstock luxury fabrics from Nona Source (deadstock being the industry term for over-ordered materials, in this case offcuts from Berluti, Lanvin, Christian Dior, Givenchy, Fendi, Loewe and Bvlgari and more), which were all printed with beautiful microbial blooms.

But how powerful will biodesign be in reducing the world’s carbon footprint?

“In theory, very. In practice, it depends on how we can manufacture some of these ideas at scale,” says Collet. The major hurdles remain investment, which she believes entails more early collaborations with brands. A proper environmental certification for biomaterials, via an independent verified auditing procedure, will also be needed to distinguish between true biodesign and greenwashing statements.

“As the industry grows, as it inevitably will, we need to stay true to the raison d’être of biodesign, which is to get a step closer to how nature makes: at ambient temperature, in cyclic system, with no toxic by-products. Biology is effectively a very old technology that has evolved over billions of years.”

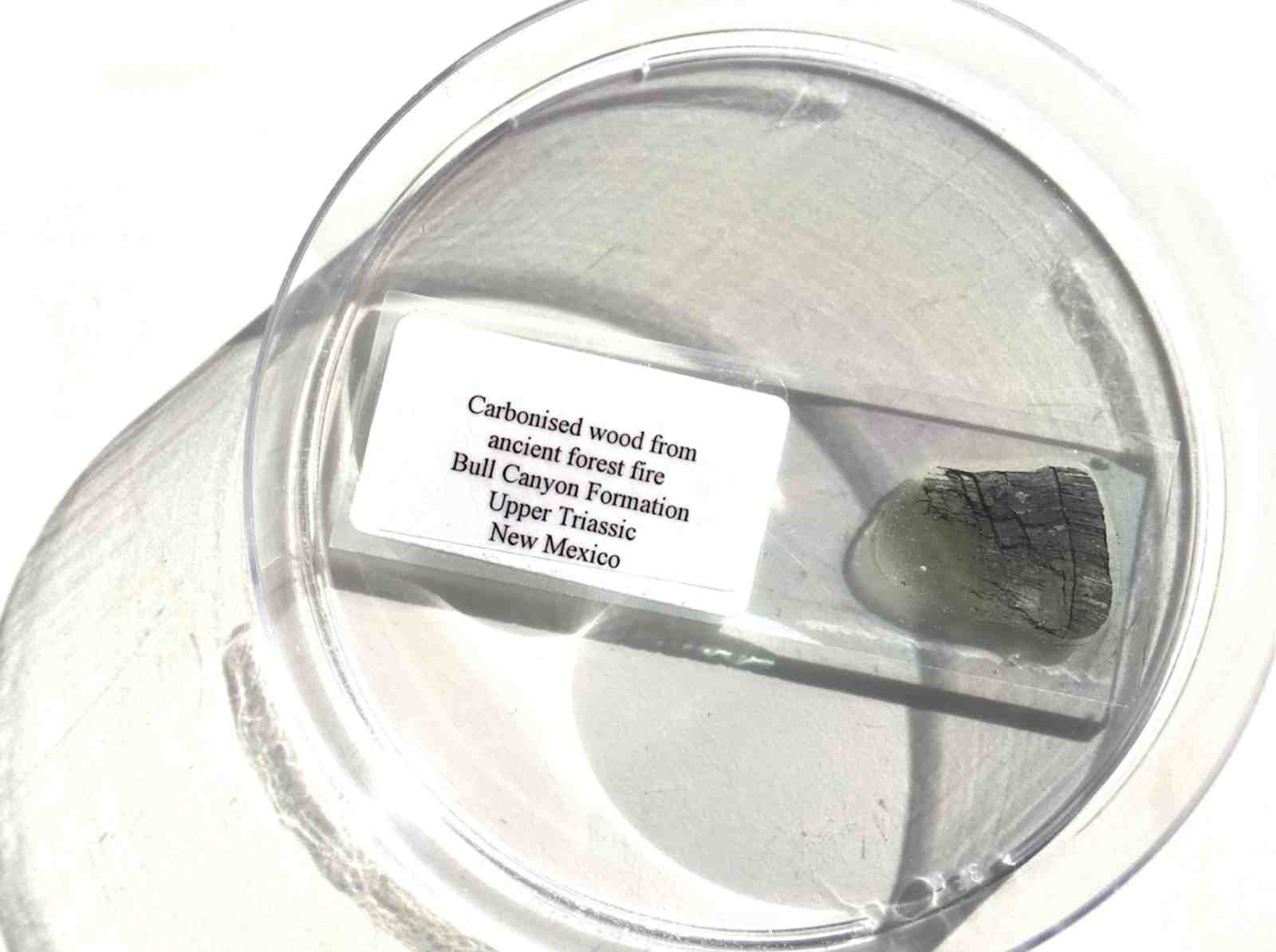

But biodesign’s applications go far beyond fashion and apparel. For British design scientist Melissa Sterry, biodesign has been a three-decade journey that started in fashion and is now centred on addressing the growing problem of wildfire resilience. “My first exploration in the field was in 1994, when I conceived of a ready-to-wear collection that could biodegrade at the end of the season and that could not only be safely reabsorbed by the environment, but provide nutrients for soils, thus plant life.” She was one of very few designers working in biodesign at the time. Thirty years into her career, Sterry has worked with biodesign across fashion, architecture, urban design, construction, planning, service design, manufacturing and more.

Today she is using biodesign with a practical application to help build resilience to wildfires. “I have family living in one of the most wildfire-prone regions of Southern California and thus hear about the issues involved in living with wildfire first-hand.”

Essentially, her work has involved studying how some plants have evolved to live with wildfire and mimicking these traits and systems, from the molecular level upwards, then migrating the traits of plants to architectural and urban resilience to wildfires. Currently seeking backers, she hopes to soon commercialise applications for residential, commercial, and civic buildings in the wildland urban interface.

Sterry is confident that all sorts of biodesign will be commercialised soon to address some of the world’s issues, as she is being increasingly asked to consult with executives in industry and government. “The nature of this work is led by practice. My reference points are concepts that having already reached prototype stage are either at, or near to proof of concept commercially. For business experts and investors that want to enter the field it’s a new frontier and place where there are copious opportunities for firsts.”