The Massive Opportunity in E-Waste

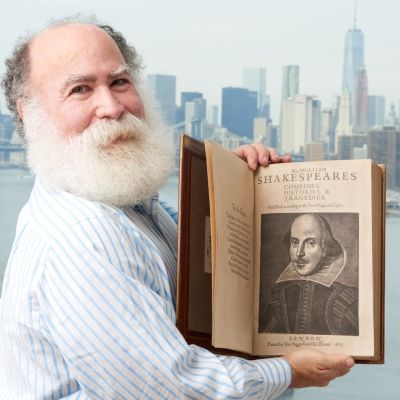

Eric Lundgren is an eco hero to many for keeping computers out of landfill.

“They just don’t get it,” says Eric Lundgren. As a teen Lundgren heard that local companies were struggling to know what to do with their old computer hardware. So, he got paid by them to take it off their hands. Years later, as the founder, in 2013, of IT Asset Partners, headquartered in Los Angeles, he started doing it for Fortune 500 companies. But he doesn’t charge. “And they still ask how much it’s going to cost them,” he says. “They really don’t get it.”

It costs nothing because Lundgren is at the forefront of recycling electronic waste. His company made US$43 million in profits last year, and, since China has closed the door to importing such waste from other countries, it is only set to grow. What others are ready to throw away, he can disassemble, using most of the parts, not to mention precious metals such as gold, silver and platinum, in new electronics, often for consumption in the developing world.

Electronic waste such as ‘old’ computers, cellphones, hi-fi equipment, TVs, kettles... anything with a plug, is a problem of epidemic proportions. Some £40 billion of recoverable materials is now discarded each year. Indeed, it is now calculated as being the world’s fastest-growing waste problem. Last year, a UN report found the amount of electronic waste had risen over the last two years by eight percent (up to 43 million tonnes, double the amount of plastic refuse) with only 20 percent being recycled. Most goes to landfill.

“We throw electronics away on the assumption that there’s some kind of solution going on behind the scenes, but there isn’t,” says Lundgren. “Some 90 percent of it is crushed for its commodity value. It’s like reducing a US$900 iPhone to US$3 of aluminium. And yet many parts in that phone could be re-used.” He’s especially bothered about batteries: those power packs set to make or break our connected, on-the-move society over the decades to come.

“Battery waste is especially bad, yet batteries can be a source of light, heat, water purification,” Lundgren explains. “Open up a device that’s been thrown away and most batteries inside are good and useable. You can take the daily waste in the US and empower, say, a whole town in Cambodia. Don’t get me wrong. I’m not against consumption. I want a life of abundance. But I want it to be efficient.”

Lundgren has made some bold moves to raise awareness of the problem. Last year he took a battery-powered car and, on a single charge, he and his team drove it a fraction short of 1,000 miles, with a Guinness Book of World Records judge there as a witness. What was remarkable was that he and his team built the car, for just US$14,000, and over 14 days, from first design to record-breaking drive, using only parts pulled from a landfill. Compare this car to Tesla’s Model S 100D, currently the longest-range electric car on the market: yours for US$92,500 and offering a range of just 335 miles.

Bona fide carmakers were quickly asking how. “We just told them to go back to their engineers because they’ve missed something,” says Lundgren. “The fact is that we calibrated our car for range. It can’t go over 100mph but I don’t think you need more speed than that. Range is the first priority for a consumer and that is what’s stopping them buying electronic vehicles now. Just as important though was the use of waste electronics to build it. This was a car of the future made from stuff that had been thrown away.”

More remarkably perhaps, it seems that Lundgren is ready to go to jail to change attitudes. Last year a US federal court sentenced Lundgren to 15 months in prison for his role in the copying, importing and selling of counterfeit Microsoft software. He’s appealing. His argument? He pled guilty to the distribution, at nominal cost, of a repair tool/recovery software — downloadable for free from Dell by any owner of a Dell computer — that allows consumers to restore their computers to factory settings in case of soft or hardware failure. As far as he’s concerned, he got in the way of the electronics industry’s love of planned obsolescence, and Microsoft’s supposed loss of a repeat sale. For him it was, he says, about keeping working computers out of landfill. For many that makes him an eco hero.

Real change, however, will only come when wider attitudes to electronics change. That’s with regards to the design ethos of manufacturers. Some mobile-phone manufacturers insist on designing products so their batteries cannot be replaced; or in a way that doesn’t allow easy hard or software upgrade; or, despite the technology having existed for some time, without using shatterproof glass for the screens. But this is also a problem with our own outlooks. We may be encouraged to upgrade our cellphones bi-annually, on average, but do we really need to? Does that scratch really mean our cellphone is in any way less functional? The falling prices of electronics only encourage such consumption.

“We have this hugely wasteful attitude to recycling electronics. Look into those things we consider broken and often it’s just a tiny element; the rest of that piece of electronics can be used for something else. But not many people even know that’s possible,” says Lundgren. “[The problem in part is that] we love newness and the manufacturers know that. We’re constantly bombarded with the idea of needing that new electronic product because it does one more thing than the old one. But I see inside a lot of electronics and I can tell you that they have identical components, just a different calibration.”

Ultimately, he, and others, argue that legislation will be required to nudge behaviours in the right direction: government mandates to make electronics easy to recycle; and taxation of those manufacturers who don’t, especially those still making products deemed ‘beyond economic repair’, which is to say cheaper to replace than fix. Only then might change come. “There has to be a political will for these things to happen but there’s real environmental damage from all this now,” Lundgren stresses. “The mercury in the fish we eat is directly traceable to electronic waste. And that’s just crazy.”