Reviving Rural Chinese Crafts

Ancient crafts are dying out of China’s rural villages as younger generations are lured by urban jobs. Elaine Ng wants to change that.

In the lush-green mountain villages of southern China’s Guizhou province, surrounded by rice paddies and ancient Banyan trees, the women have an unusually beautiful method of embroidery and batik painting.

Dating back many hundreds of years, Guizhou textiles are known for their complexity, sophistication and variety, with a bold, expressive aesthetic. Motifs symbolise myths and cultural celebrations. While the patterns have never been documented, they have been handed down aurally, mother to daughter, over many generations.

Both weaving and printing involve an intensely manual process. Villagers harvest leaves and grind them into a paste to make the indigo dye for batik. Patterns are applied to undyed cloth using liquid beeswax. When the cloth is submerged in dye, the waxed parts remain white while unwaxed parts absorb the colour. For the embroidery, each household has its own loom that must be maintained and looked after.

But now things are changing. The next generation of girls is leaving the village to find better-paid work in factories in the city, meaning the old skills are dying out. Now only 10 percent of women in the villages retain the craft knowledge of their ancestors.

When British-born, Chinese designer Elaine Ng first visited the villages in 2013 she discovered amazing artisans who were unable to communicate their skills. “They are a tiny ethnic minority and only speak a local dialect, not even Mandarin. So, they couldn’t bridge the gap to the modern world.”

She was saddened by the loss of heritage and decided to help the village. Having graduated from Central Saint Martins in London with an MA in Textile Futures, Ng knew a thing or two about textile design. At first, culture and communications were at loggerheads. “I made huge mistakes. I brought lots of technical information that I thought was me being professional, but they were very offended,” recalls Ng. “It took a long time for us to get back together and understand each other.”

With perseverance, she managed to win their trust. “Understanding their limitations, I experimented with new materials with them, without changing their process. Replacing the warp with high-strength transparent nylon gives the material extra property,” says Ng. She also shared warp-calculating techniques with the local weavers in order to help them make multi-coloured warps.

Ng wanted to continue helping the village, but she soon ran out of money. In 2015 she applied for a grant from Hong Kong’s Design Trust, which she won. Ng invested the funds in the village, employing local builders to build an industrial-scale dye vat for batik printing and bigger looms to enable larger-scale production. “By slowly growing the villagers’ assets, we are providing them with a sustainable way of living,” she says.

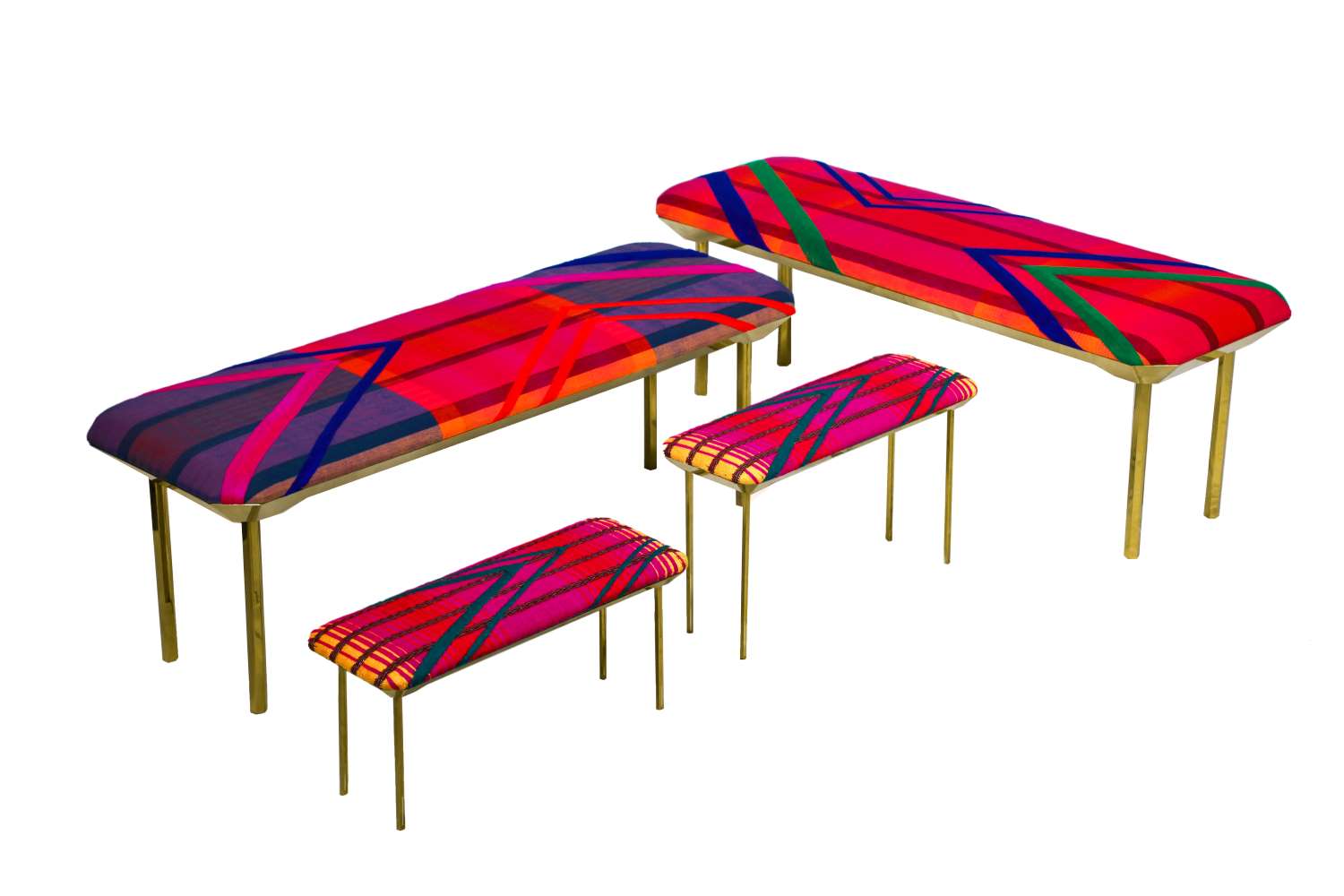

Ng launched a heritage textile design brand, Unfold Stories, under her umbrella company The Fabrick Lab, which uses heritage textiles with technology in lifestyle and home-furnishing products. “It’s made for consumers who want to spend meaningfully and enjoy seeking a sustainable lifestyle,” says Ng. “The brand is to help ethnic minorities use their old skills across different platforms to keep traditional techniques alive while inspiring modern consumers with the craftsmanship.” Six families from the original village are employed full time through Un/Fold, and she hopes to expand to include more families in future. The product range now includes scarfs, stools, coasters and cushions, and are on sale at Lane Crawford, a high-end Hong Kong retail mall, and can be seen in the interiors of restaurant Potato Head in Hong Kong and Bali. Hotels are also interested in the designs on a larger scale but must commit to buying some original pieces as part of the package, says Ng. There is also an online store, theunfoldstories.com. “Through e-commerce we are hoping to create a positive impact.”

When some of the daughters who went to work in the factories came back home, they saw their mothers and the ancient skills in a new light, says Ng. “The daughter came in and said: ‘oh wow, mom, you’re really cool!’ and the mom had no idea what she was talking about,” laughs Ng.

She adds: “The next generation don’t want to be stuck in the village like their mothers and grandmothers were. But they’re happy to be in the village if it’s by choice. As long as craft can earn them enough to buy the latest iPhone, these girls might change their minds.”

This article originally appeared in billionaire's Earth Issue, September 2019. To subscribe contact