Turkey's Bilbao Effect

Billionaire Erol Tabanca doesn’t believe in art being locked away. Hence his creation of a major modern art museum in his Turkish hometown.

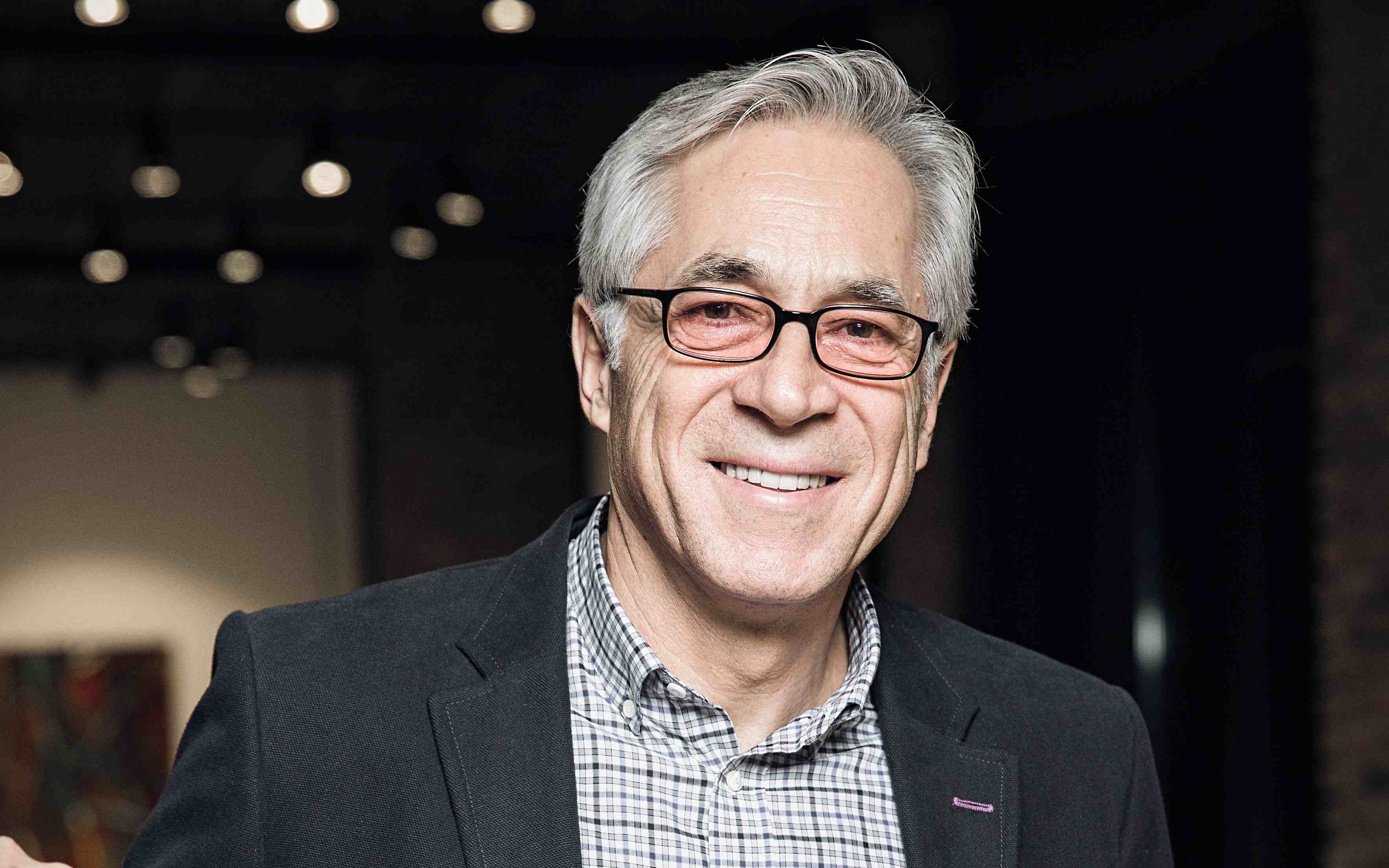

“It was only when galleries started to ask me what I was buying at the moment that I realised I’d become an art collector,” laughs Erol Tabanca. “But I’ve always had an interest in contemporary art. I started buying small paintings and art objects 15 years ago and my collection just grew piece by piece from there.”

Indeed, such was the size of his collection that it was used to decorate the big white walls of the sizable headquarters of the Polimeks construction company in Istanbul. Tabanca founded Polimeks in 1995 with US$30,000, turning it into a company behind US$11 billion of projects to date, amounting so far to some 134 buildings, from hospitals to Olympic stadia, airports to government offices and Russia’s first Ritz-Carlton hotel. And now a museum.

“We reached the point when we started to run out of room for the art,” says Tabanca. “But, more to the point, I don’t believe that art should be locked away. It should be available for as many people as possible to see. In fact, I don’t understand why other art collectors don’t want to share their collections. I think if we have the opportunity we should contribute to society in some way. In this case it’s in sharing art.”

To this end, Tabanca has initially put US$11 million of his own money into the creation of the Odunpazari Modern Museum (OMM), which opens this month in Eskişehir, a university town on the banks of the Porsuk River in northwest Turkey. It’s Tabanca’s hometown, where he also studied architecture. Designed by Japanese architect Kengo Kuma and Associates, the three-storey, 4,500-square-metre museum was inspired by the traditional Ottoman wooden cantilevered houses synonymous with the locality.

The permanent collection will be a mix of some 1,000 international post-1950 works by Julian Opie, Marc Quinn, Massimo Giannoni, Robert Longo and Alfred Haberpointner; alongside acclaimed Turkish artists such as Canan Tolon, Haluk Akakçe, Taner Ceylan and Gülsün Karamustafa. The inaugural exhibition, curated by Haldun Dostoğlu, founder of Istanbul’s Galeri Nev, will showcase some 200 words by 60 leading artists from Turkey, and will open with a new site-specific commission by Japanese bamboo artist Tanabe Chikuunsai IV.

Tabanca hopes that the new gallery will help raise the profile of Turkish art. “The international art scene is that much faster and more global now that there’s a danger of Turkish art being left behind in terms of reputation. Traditional Turkish artists are well known; the contemporary ones less so,” he says. Tabanca also hopes the gallery will boost tourism and the local economy: Eskişehir is widely considered to be Anatolia’s capital of culture, with its Odunpazari old town district on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists. But, says Tabanca, it needs an additional nudge to get it the recognition it deserves.

“Yes, it would have been more logical in many ways to have built the OMM in Istanbul,” adds Tabanca, “but then the city has plenty of museums already. The impact wouldn’t have been the same there. Eskişehir is a young city with young people, which I think is important when showing art. It seemed better to bring the energy that a new gallery can provide to a new town. Since we chose a Japanese architect and installation artist, we’ve already met with the Japanese tourist board to devise a programme of action to get Japanese tourists to the region.”

Indeed, Tabanca is hoping for something of the so-called Bilbao Effect: named after the decision to open, in 1997, the Frank Gehry-designed Guggenheim Museum in what was then a sleepy, underserved Spanish city. This transformed Bilbao’s economy to the tune of bringing in four million tourists and €500 million in business over the following three years alone.

Tabanca hasn’t even put his name to the OMM. “Really, it didn’t cross my mind to put my name on it,” he laughs. “My grandfather still lives in the town, very near to the museum, so I’m more interested in the town’s name becoming better known.”

His daughter, Idil Tabanca, is likely to see her profile rise as she now heads the museum’s board. Erol Tabanca’s name will probably remain in the background, certainly relative to that of his fellow Turkish billionaires. Many of them have been dethroned by Turkey’s recent currency crisis, which saw the Turkish lira hit a record low against the US dollar, wiping US$23 billion off the collective net worth of the nation’s top 35 tycoons. But Tabanca’s impact on the cultural standing of many cities across the wider region has been considerable, even if the OMM is a decidedly more personal project.

He says: “This is a philanthropic gesture, even if there’s a personal element to it: with its opening in some way I feel I’ve completed a mission in passing the baton to my daughter, who will have a younger view on important art to come.

“I feel that art matters. Yes, there’s an argument for saying that I could have used the same money to build, say, a hospital. But I think that art brings health, as well as education and emotional support. Art is food for the soul. Am I going to miss not having the collection around me at work? I have lots of old friends in Eskişehir and this will give me a good excuse to visit them more often.”

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Art Issue, June 2019. To subscribe contact