The Dinosaur Hunters

Technology for mapping Mars is helping scientists to unearth new fossils that could rewrite our ancestral history.

It’s not every day you discover a new dinosaur species, let alone three. But during a recent expedition into Mongolia’s Gobi Desert led by The Explorers Club, scientists identified bones from an ostrich-type dinosaur, a turtle-like dinosaur and the neck vertebrae from an unknown dinosaur from 70 million years ago.

These discoveries went along with more than 250 new fossil locations, five entirely new areas previously not known to contain fossils, and hundreds of fossilised bones, including those of mammals, which were not previously known to have existed in the area.

It was using NASA technology — the same technology that recently unearthed lakes on Mars — that made these finds possible.

"This rate of discovery is unheard of,” explains Michael Barth, chairman and founder of the Hong Kong chapter of The Explorers Club, a 115-year-old expedition organiser that counts Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos and James Cameron as members. Berth organised the 20-day mission as part of a tribute to the 100-year anniversary of the first paleontological foray into Central Asia by US scientist and adventurer Roy Chapman Andrews.

Andrews, who would later become the inspiration for George Lucas’s Indiana Jones, led a series of wildly intrepid expeditions into the Mongolian Gobi to prove that the cradle of mankind was in fact in Central Asia, as opposed to East Africa. He was the first palaeontologist to swap camels for cars, which meant his team could cover a great deal more ground.

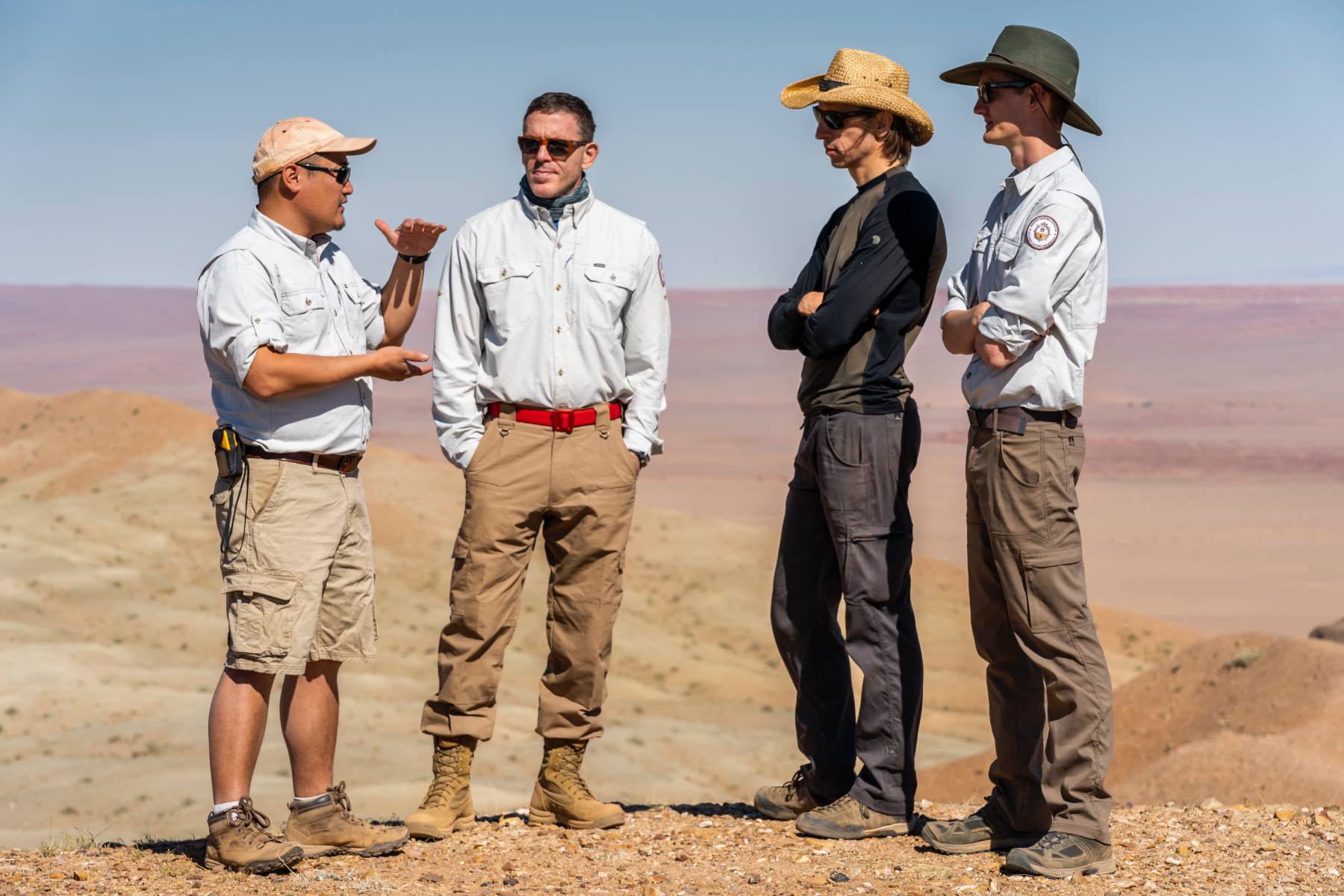

“In tribute to those initial discoveries that were made possible by Ray’s innovation and vision, we wanted to be just as innovative if not more,” says Barth. “So, the question came about, what tech was out there today that we might apply to palaeontology in the field? This how we got to the point where we decided remote-sensing and advance-mapping tech was the key, to be able to see everything that would have been invisible to the original team, and to unlock the sense of discovery for the next 100 years, and put local experts in control,” he adds.

Barth assembled a team of 35 palaeontologists, archaeologists, geologists and scientists to go to the Gobi Desert in July, using advanced-mapping technology data collected from satellite and drone imagery to pinpoint high-probability locations for fossilisation, based on geological and sedimentary markers. Their first point was in the Oosh mountain region in the Ömnögovi territory of the Gobi Desert, the first site explored by Andrews in 1922.

But while Andrews took a team of Dodge motor cars with 25 horsepower engines a century ago, the team in July took a fleet of very comfortable Infiniti SUVs to prospect for fossils.

The combination of NASA satellite and drone imaging used in palaeontology has never been done before. It represented a new, more efficient, method of discovering dinosaur fossils.

“It was a game-changer, said Barth. “Palaeontologists can redraw the geological map with greater precision, which has a ripple effect on other questions that are being contemplated, from climate change to finding water on Mars.”

The first Velociraptor ancestor fossil was discovered in the Oosh mountain range, the first evidence of a carnivorous dinosaur in the area. The team also found the ancestor of the great horned rhino, again, never been seen before in this region. It also found an exceedingly rare Theropod dinosaur egg and massive vertebrae, ribs, skull fragments and the tail section from a Tarbosaurus, the Mongolian cousin of the Tyrannosaurus rex.

“Up to now, palaeontologists have done a lot of prospecting by walking around in a landscape to interpret its geological properties,” says Dr Scott Nowicki, lead R&D scientist at Quantum Spatial, who compiled the satellite and drone-mapping technology. Dr Nowicki has worked on several Mars explorations with NASA.

“With a selection of drones, we flew a multispectral camera, a thermal camera and invisible cameras over four sites and collected data over hundreds of kilometres. We then compared that to satellite data, correlating the observations made on the surface with geological properties that we had not yet visited. The three-dimensional maps we created, down to the centimetre level, will aid in the exploration of the Gobi for years to come,” he adds.

Importantly, the trip will also be a game-changer for the team of local palaeontologists in Ulaanbaatar, who, until now, have lacked the resources and recognition they deserve. “I approached the expedition partly as a long-term development project,” explains Barth. “We wanted to bring technology and resources to the local expertise. Now the real work is just starting. New species are being analysed at their lab and we want to train local geologists to fly drones to map more of the Gobi. For the Mongolians we’ve given them the keys to taking control over the discovery of their own resources for the next 100 years at least,” he says. He adds that should anyone want to retrace the steps of Ray Chapman Andrew themselves, he can make an introduction to the local team.

For its next adventures, The Explorers Club is looking to Bhutan, Uzbekistan and a remote part of the US. Like the Mongolian trip, all will have an element of long-term development for the local area and its inhabitants. Each one takes about a year to plan and organise.

But a moment that will stay with him for the rest of his life, says Barth, is the moment he personally uncovered a dinosaur egg. “The hair on the back of my neck is standing up thinking about it,” he describes. “One-hundred million years old and you could still see part of the egg that cracked when the baby hatched. We found lots of bones, but there was something so visceral about finding that egg.”