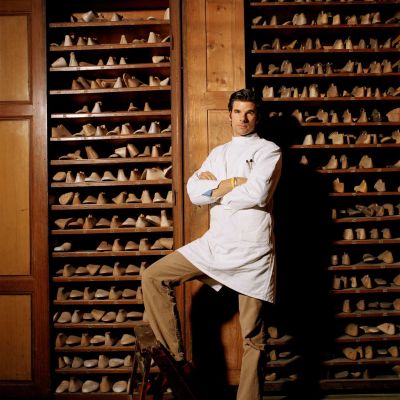

True Vision

Billionaire Tej Kohli is on a mission to eradicate blindness from the world.

Delhi-born billionaire Tej Kohli is trying to do for avoidable corneal blindness what Bill Gates set out to achieve for malaria: complete eradication.

Kohli, a London-based electrical engineer in his 60s, made his fortune during the dotcom boom, selling e-commerce payment software. He enjoys the finer things in life, with an enviable collection of supercars, two private jets and membership to any club in London worth belonging to. He describes his mantra for success as, “one word: innovation” and is a believer in inventing new technologies to build a better world.

It comes as no surprise that he also wants to tear up the rule book when it comes to his philanthropic work.

Kohli’s head was first turned towards the needless suffering of corneal blindness when he was on a trip to India. “Someone came to me and asked me to support a cornea transplant,” he recalls over the phone from London. Kohli, with his Costa Rican wife Wendy, was already doing charity work with disabled children in her hometown. He funded the operation, a man in his mid-50s who had developed corneal blindness when he was 15. Kohli was in the same room with the blind man when they removed his bandages and he saw his wife and children for the first time.

There was something so powerful about that moment, the simplicity of the operation, that the mission of corneal blindness reverberated with him. Kohli decided to take on the job of eradicating it forever.

“There are many great philanthropists supporting disease eradication — polio, malaria, cholera — but no one has really looked at blindness because it is not life-threatening,” says Kohli. “And I strongly believe if you’ve had the good fortune of making some money, and we have, you have to give back to society.”

Currently there are 39 million people in the world who are blind, according to the World Health Organization, with most of those living in poverty. Yet a good proportion of blindness is curable: 12.7 million of the world’s blind are waiting for cornea transplants; most end up waiting indefinitely.

Kohli discovered that the cost of surgery is completely prohibitive for most. If you’re earning US$10 a week, you can’t afford the train fair to hospital, let alone a surgery that costs US$2,000 plus in India using donor cornea (or US$20,000+ in the West using synthetic cornea). Then, even if you do receive a transplant, you have to take drugs for the rest of your life to stop rejection, a further impossible expense for most poor people.

“Most people with corneal blindness are too scared to even go to the doctor in the first place for fear of costs, or live too far away from hospitals to consider it,” he says.

Kohli knew there must be a better way. So began a dual approach. On one hand his foundation, the Tej Kohli Cornea Institute, goes to rural villages in India to give people treatment using the old-fashioned method of transplanting a human cornea. The Tej Kohli Foundation, goes to rural villages in India to give people treatment using the old-fashioned method of transplanting a human cornea. The Foundation’s Tej Kohli Cornea Institute in Hyderabad, for example, over the last two years saw 190,070 outpatients and carried out more than 17,000 cornea replacement surgeries. Their approach is to target the remotest villages, usually with a ‘pop-up-’ tent and operating table in a community, carrying out as many as 1,000 cornea transplants in a month. The Foundation also supports the LV Prasad Eye Institute, a World Health Organization collaborating centre, which has more than 100 clinics across India.

But his Foundation has taken a further step: to develop a liquid biosynthetic alternative that won’t require surgery and will be applied through a syringe like a vaccine; eliminating the need for a donor and follow-up drugs. “Getting the technology right is the key. You can’t just keep giving money to existing ways of doing things, you’ve got to reinvent new technological solutions,” he says.

This year he also donated US$2 million to Massachusetts Eye and Ear (MEE) in Boston, a teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School, to help with the development of promising biotechnology solutions. The move is part of Kohli’s goal to eradicate corneal blindness by 2035, something he has given tens of millions to so far. However his biosynthetic treatment is still in trials to gain Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval from the US, which may take another five to ten years before it can be put into practice, Kohli says with visible frustration.

When it comes to giving back, Kohli is very particular. He is a proponent of what he calls “grassroots philanthropy”, directly funding the hospitals and doctors doing the operations and the universities researching the liquid biosynthetic. He says for many would-be philanthropists, the question of whether to give directly or via a charity is often what holds them back. “There are people who want to donate, especially first-generation billionaires and millionaires but they don’t know where to put their money. It’s a dilemma because there have been high profile cases of charities with exorbitant administration costs or even fraud. Most wealthy people, myself included, would hate to put their money into something that doesn’t have the desired effect.” His advice for budding philanthropists is to give to programs in schools or universities where you can see the outcome of a specific spend and its full application, and there are no “black boxes”.

He points to Bill Gates, a man he deeply admires, for “not wasting money” and engaging directly with his mission by going into communities in Africa for himself. “But most people don’t have the time or passion to do the grassroots work, it’s literally like running another business. I’ve had a lot of people call me up and ask if they can give to my foundation. Even Richard Branson offered when I was in Necker Island recently.”

Kohli turned down Branson’s offer – for now – until they gain FDA approval for the liquid biosynthetic cornea replacement.

At that point it will become a low-cost solution to cure millions, and to rapidly scale up, it will cost “a few billion”, says Kohli. When that happens, he will be happy to accept Branson’s, and other philanthropists’, help.

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Health Issue, December 2019. To subscribe contact