The Art of Champagne

The storied history of Ruinart goes to show that being small in size, while big on quality, can be a blessing.

How does a Champagne maison survive three centuries when so many others are swept away in the tides of time? For Ruinart, the world’s oldest Champagne brand, it’s a combination of good fortune, being under the radar, and an unwavering dedication to quality.

It started with a monk. The House of Ruinart was founded in 1729 by Nicolas Ruinart. But it was his uncle, a learned Benedictine monk called Dom Thierry Ruinart, who had the vision.

He foretold that this new “wine with bubbles”, developed in his native region of Champagne and that the royal courts of Europe adored, was destined for a bright future.

The creation of the House of Ruinart coincided with the dawn of the Enlightenment in France and of the French ‘art de vivre’. There arose in France a true culture of everything good and beautiful, favouring fine and elegant, light and sophisticated, and the house selected Chardonnay as the common thread for all its cuvées.

But in the last century there were two points when Ruinart nearly didn’t make it; after the Second World War the group was on its last legs with just 800 cases of wine in its cellar and only two customers in Paris: the restaurant Maxim’s; and an upscale bar, Le Sphinx. The Chardonnay grape had gone through a phase of unpopularity.

“The Chardonnay grape didn’t exist before the end of the 19th century in Champagne, it was all Pinot Noir or Pinot Meunier,” explains Frederic Dufour, global chief executive of Ruinart. “When Chardonnay came in, for a long time it was not perceived as a noble grape, it was just an add-on to Pinot Noir.

“But after the Second World War, the taste profile suddenly evolved and people were looking for a more elegant wine, easier to drink, lighter,” he says. Ruinart was at the forefront of this Chardonnay-led evolution for the more casual, and frequently female, drinker. Later in the 1990s, Ruinart would become the first to make a Blanc de Blanc Champagne, a designation of wine made using solely Chardonnay grapes.

There was another difficult period, explains Dufour. After a series of bad harvests in the early 1960s the Ruinart family was faced with either compromising on the quality of its grapes or selling the business. After much hand-wringing it sold the company to Moët & Chandon in 1963. Moët & Chandon had planned to stop production completely and use the site for other things, as Ruinart was tiny (a meagre 15 hectares) and losing money, according to Dufour. But because of an oversight and then a merger with Hennessy in the 1970s, it did nothing for over 20 years and the vineyard quietly ticked on.

“When Louis Vuitton bought Moët & Hennesy in the 1980s, it discovered there was this little historic jewel that everyone had forgotten about,” explains Dufour. So it decided to reinvest in it, doubling down on its storied history and even bringing back the original curvaceous bottles.

This goes to show that being small in size, while big on quality, can be a blessing. Dufour, eight years its CEO, has no intention of changing Ruinart’s identity of small yet perfectly formed. “We don’t want to target mass; we don’t want to shout; we want to target knowledgeable hedonists who appreciate the beautiful things in life.” He has, however, increased its overseas customer base, from 70 percent French when he took the reins, to a 50/50 international and French split today.

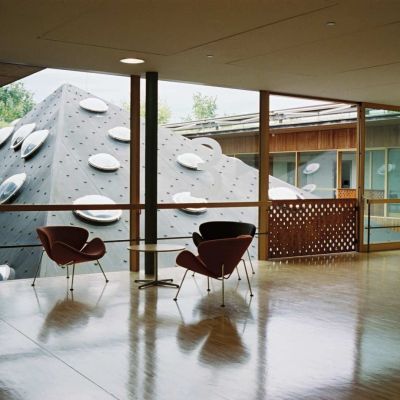

The brand, in Dufour’s words, is one that speaks of quality, a historic ‘savoir-faire’. It has long been associated with artists, from 1896 when André Ruinart asked the greatest illustrator of his time, Alphonse Mucha, to create an advertisement that became an icon. Ruinart positions itself in the VIP lounges of art fairs, not polo matches. It cultivates an association with artists all over the world, last year sponsoring the Chinese artist Liu Bolin who appeared to ‘disappear’ in front of its iconic vineyards and cellars. The brand uses art to balance tradition, explains Dufour.

Rarity helps to cultivate mystique. While Dufour refuses to disclose production, Ruinart’s tiny 15 hectares is dwarfed by its LVMH sisters, Moët & Chandon (1,190 hectares) and Veuve Clicquot (515 hectares). “We always have more demand than supply.”

And it’s exceptional quality. Since he has been exclusively drinking Ruinart, Dufour claims he has not had a hangover.

“With a bad Champagne you have a hangover within five minutes; a medium Champagne, the next day; and a good Champagne, never. He says he can drink a magnum of Blanc de Blanc in one day and feel unscathed the following morning, although he is careful to keep hydrated. “It’s very light, that’s the beauty, the finesse and elegance of the wine.”

And what about the future? Nearing its 300th anniversary, Dufour wants Ruinart to be synonymous with sustainability. “We aim to embody conscious luxury,” he says. Already Ruinart has overhauled its packaging and logistics using clean solutions. Its tractors working the vineyards are run on electricity and it uses drones to minimise pesticide usage. It sells its out-of-date materials to workers at cost price and donates the money to a foundation. It also invests in social projects, such as the French start-up sea-bubble, which aims to be the carbon-free river Tesla of the future. Dufour says that he would like his lasting mark as CEO to be that Ruinart is perceived as “the most conscious sustainable-minded Champagne house on the planet”.

He adds: “I don’t think this world can continue the way it is. We have to respect and improve the social aspect. This product comes from the earth, so we have to give back to it.”

This article originally appeared in Billionaire's Giving Issue, December 2018. To subscribe contact